|

|

Saugus-Newhall Airport

|

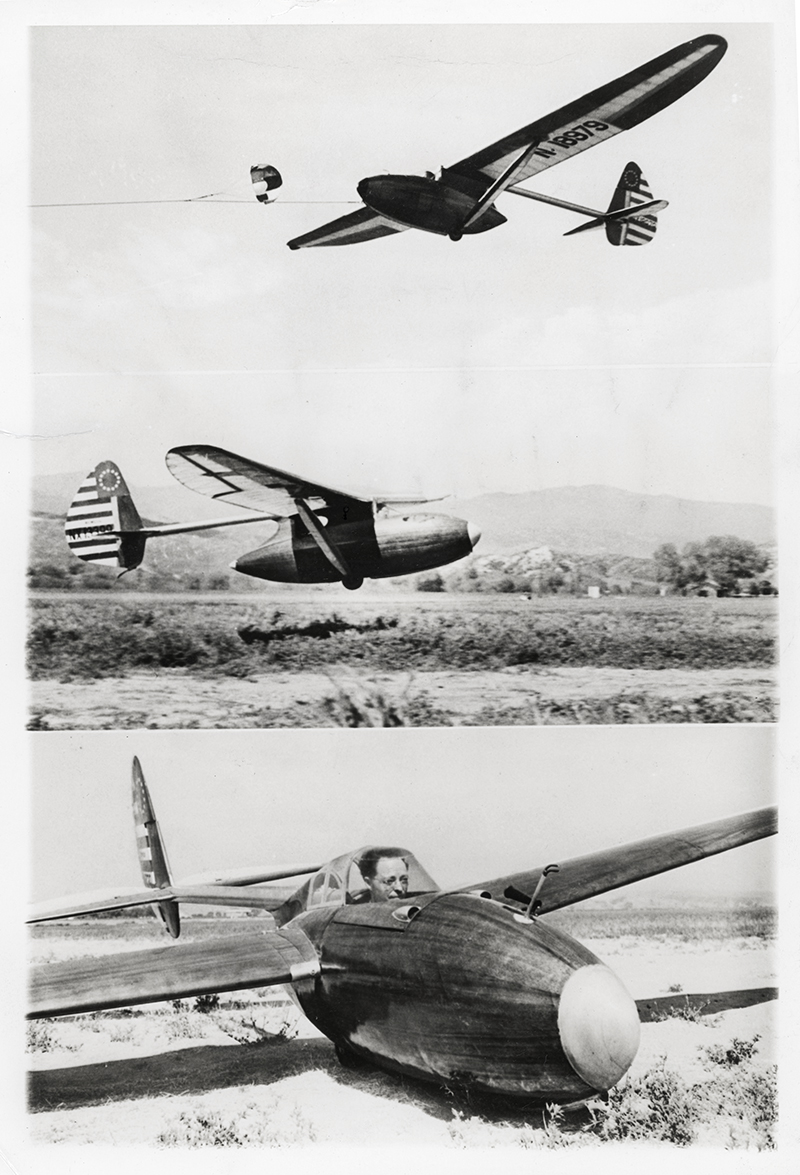

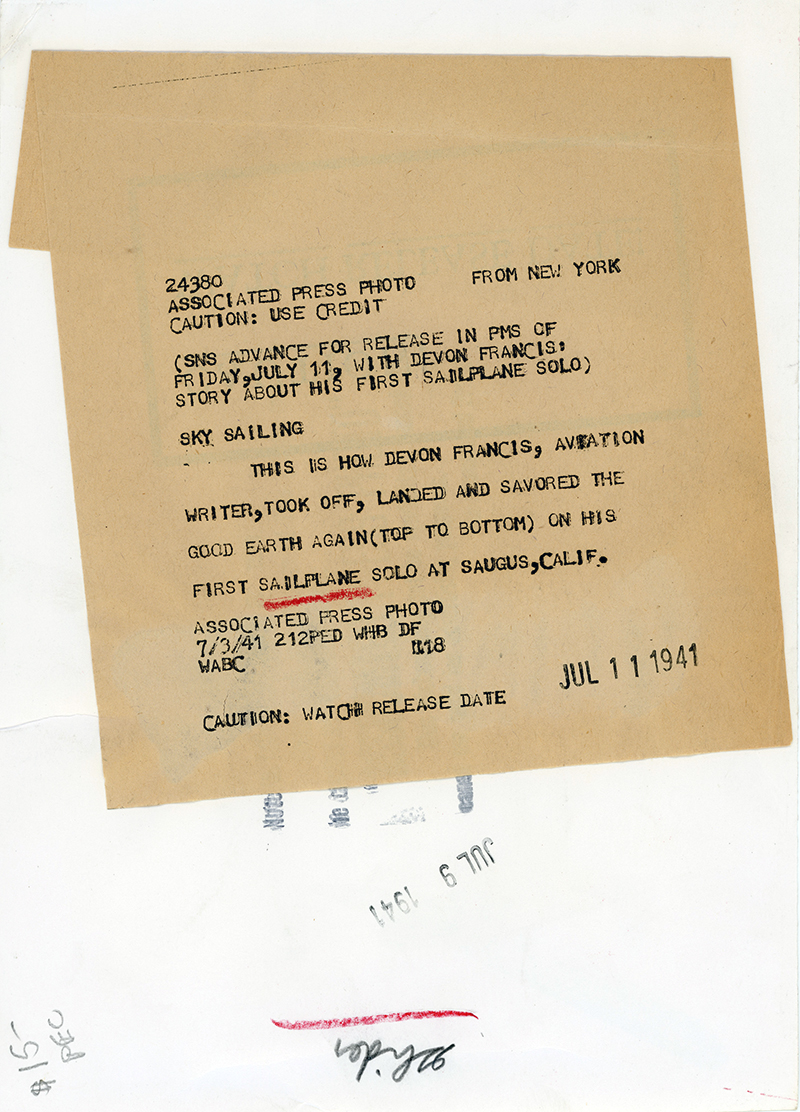

Aviation correspondent Devon Francis takes his first solo glider flight at the Saugus Airport (later called Newhall Airport) in 1941 and lives to write about it. Overseeing the flight is the famous aviation pioneer Hawley Bowlus, who had superintended the construction of Charles Lindbergh's Spirit of St. Louis in San Diego in 1927. Both Bowlus and Lindbergh were quite familiar with the Saugus-Newhall area and were known to test gliders here. (Search this site.) The glider Francis is piloting, tail No. N-18979, is a 1-seat 1939 Bowlus BA-100 Baby Albatross. Decommissioned July 19, 1971, it was last registered to a private individual in St. Paul, Minn.; today it resides in the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum's Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Va. Cutline to AP wirephoto from an unknown newspaper archive reads: 24380 / Associated Press Photo / From New York / Caution: Use Credit (SNS Advance for release in PMS of Friday, July 11, with Devon Francis: Story about his first sailplane solo) SKY SAILING This is how Devon Francis, aviation writer, took off, landed and savored the good Earth again (top to bottom) on his first sailplane solo at Saugus, Calif.

Assocated Press Photo

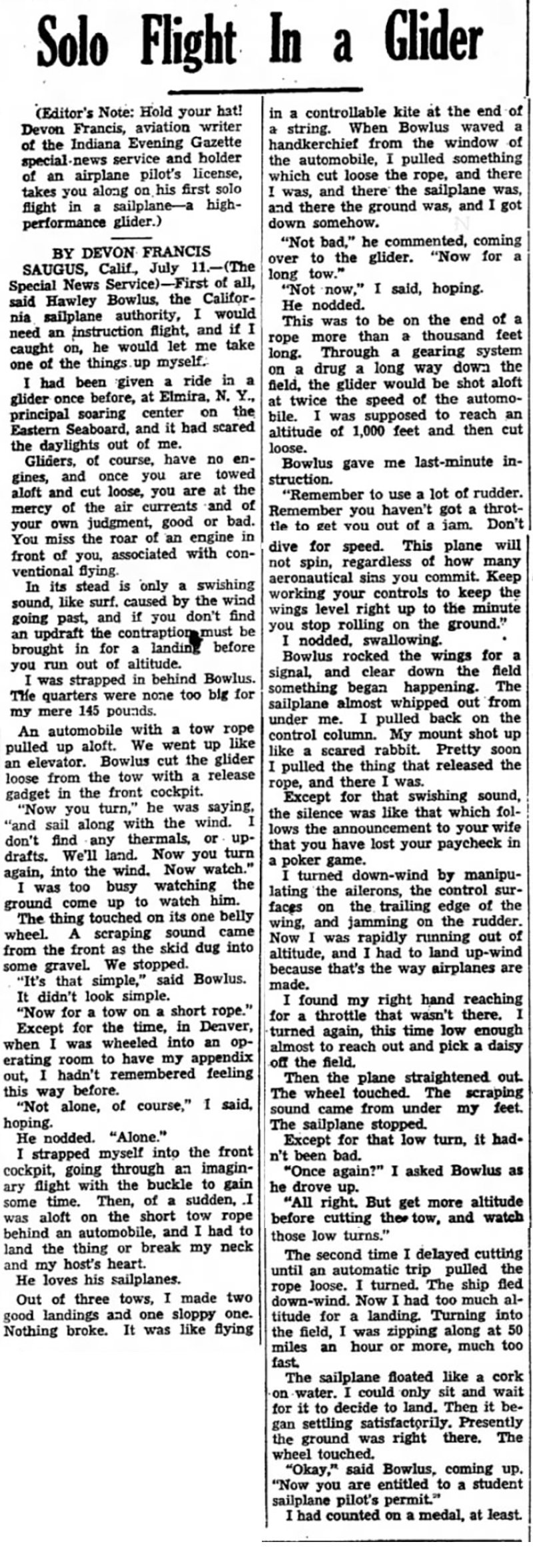

Solo Flight In a Glider. Indiana Evening Gazette | Friday, July 11, 1941. [Newspaper] Editor's Note: Hold your hat! Devon Francis, aviation writer of the Indiana Evening Gazette special news service and holder of an airplane pilot's license, takes you along on his first solo flight in a sailplane — a high-performance glider. By Devon Francis Saugus, Calif., July 11. — (The Special News Service) — First of all, said Hawley Bowlus, the California sailplane authority, I would need an instruction flight, and if I caught on, he would let me take one of the things up myself. I had been given a ride in a glider once before, at Elmira, N.Y., principal soaring center on the Eastern Seaboard, and it had scared the daylights out of me. Gliders, of course, have no engines, and once you are towed aloft and cut loose, you are at the mercy of the air currents and of your own judgment, good or bad. You miss the roar of an engine in front of you, associated with conventional flying. In its stead is only a swishing sound, like surf, caused by the wind going past, and if you don't' find an updraft the contraption must be brought in for a landing before you run out of altitude. I was strapped in behind Bowlus. The quarters were not too big for my mere 145 pounds. An automobile with a tow rope pulled [us] aloft. We went up like an elevator. Bowlus cut the glider loose from the tow with a release gadget in the front cockpit. "Now you turn," he was saying, "and sail along with the wind. I don't find any thermals, or updrafts. We'll land. Now you turn again, into the wind. Now watch." I was too busy watching the ground come up to watch him. The thing touched on its one belly wheel. A scraping sound came from the front as the skid dug into some gravel. We stopped. "It's that simple," said Bowlus. It didn't look simple. "Now for a tow on a short rope." Except for the time, in Denver, when I was wheeled into an operating room to have my appendix out, I hadn't remembered feeling this way before. "Not alone, of course," I said, hoping. He nodded. "Alone." I strapped myself into the front cockpit, going through an imaginary flight with the buckle to gain some time. Then, of a sudden, I was aloft on the short tow rope behind an automobile, and I had to land the thing or break my neck and my host's heart. He loves his sailplanes. Out of three tows, I made two good landings and one sloppy one. Nothing broke. It was like flying in a controllable kite at the end of a string. When Bowlus waved a handkerchief from the window of the automobile, I pulled something which cut loose the rope, and there I was, and there the sailplane was, and there the ground was, and I got down somehow. "Not bad," he commented, coming over to the glider. "Now for a long tow." "Not now," I said, hoping. He nodded. This was to be on the end of a rope more than a thousand feet long. Through a gearing system on a [] drug a long way down the field, the glider would be shot aloft at twice the speed of the automobile. I was supposed to reach an altitude of 1,000 feet and then cut loose. Bowlus gave me last-minute instruction. "Remember to use a lot of rudder. Remember you haven't got a throttle to get you out of a jam. Don't dive for speed. This plane will not spin, regardless of how many aeronautical sins you commit. Keep working your controls to keep the wings level right up to the minute you stop rolling on the ground." I nodded, swallowing. Bowlus rocked the wings for a signal, and clear down the field something began happening. The sailplane almost whipped out from under me. I pulled back on the control column. My mount shot up like a scared rabbit. Pretty soon I pulled the thing that released the rope, and there I was. Except for that swishing sound, the silence was like that which follows the announcement to your wife that you have lost your paycheck in a poker game. I turned down-wind by manipulating the ailerons, the control surfaces on the trailing edge of the wing, and jamming on the rudder. Now I was rapidly running out of altitude, and I had to land up-wind because that's the way airplanes are made. I found my right hand reaching for a throttle that wasn't there. I turned again, this time low enough almost to reach out and pick a daisy off the field. Then the plane straightened out. The wheel touched. The scraping sound came from under my feet. The sailplane stopped. Except for that low turn, it hadn't been bad. "Once again?" I asked Bowlus as he drove up. "All right. But get more altitude before cutting the tow, and watch those low turns." The second time I delayed cutting until an automatic trip pulled the rope loose. I turned. The ship fled down-wind. Now I had too much altitude for a landing. Turning into the field, I was zipping along at 50 miles an hour or more, much too fast. The sailplane floated like a cork on water. I could only sit and wait for it to decide to land. Then it began setting satisfactorily. Presently the ground was right there. The wheel touched. "Okay," said Bowlus, coming up. "Now you are entitled to a student sailplane pilot's permit." I had counted on a medal, at least. History of SCV airstrips by Larry Westin: The Saugus Airport, later known as the Newhall Airport, was an intermediate field along the airway — "intermediate" meaning it wasn't a scheduled airline stop, rather an airport used if an airliner needed to divert from a planned destination. For instance, fog in the San Fernando Valley might require a landing farther north at a slightly higher elevation that wasn't shrouded in fog — such as Saugus. At first, U.S. airways were lighted; that is, beacons on top of towers were used for airliners of the 1920s and 1930s to navigate at night — but not in bad weather. Saugus was beacon 3A along the lighted airway from Los Angeles to San Francisco. Its runway was 2,470 feet long, 600 feet wide. The 1930 diagram shows its approximate position relative to San Fernando Road (aka Railroad Avenue/Bouquet Canyon Road). Sometime in the 1930s, four-course radio beacons were set up for aircraft navigation. This was a leap ahead of the light beacons and lighted airways, as these radio ranges were all-weather. A radio beacon was established and identified as the "Newhall" beacon, operating on 209 KHz, with the Morse code identifier of NH. These early radio beacons were limited to four courses. The Newhall beacon was initially part of the Amber 1 airway; later it also was part of the Green 4 airway. A 1943 map shows the airfield named "Newhall" (not Saugus) at an elevation of 1190 feet above sea level. A 1946 aeronautical chart shows the airport as Newhall, elevation of 1207 feet, with a 4,000-foot-long runway. It still has the 3A lighted airway beacon, 4-course radio beacon 209 KHz, identifier NH. A 1951 aeronautical chart shows the airport as Newhall, elevation of 1207 feet, with a 4,000-foot-long runway. The lighted beacon is no longer shown; the radio beacon is 209 KHz, new identifier EHA, 4 courses. Also in 1951, a new airport is shown: the 6-S Ranch, elevation 1350 feet, with a 2,600-foot-long runway, located about where Whites Canyon Road in Canyon Country is today. A 1960 aeronautical chart no longer shows Saugus or Newhall having an airport. The radio beacon 4-course range at 209 KHz, identifier EHA, now makes up the southwest end of Green 4 airway. The 6-S Ranch airport is still shown, elevation 1349 feet, runway 2,500 feet long. A 1962 aeronautical chart no longer shows any airport in the Saugus/Newhall/Canyon Country area. (Established in 1946, the 6-S Ranch Air Park closed in 1960, upon the death of its owner. It became the North Oaks housing tract.) In 1962 the radio beacon 4-course range was still operational on 209 KHz, identifier EHA. While in 1962 many 4-course radio ranges still existed, the "colored" airways were no longer shown. Most airways switched to the "Victor" airways using VHF omni-directional (360-course) radio navigation stations. After this time, aeronautical facilities in the Santa Clarita Valley no longer existed.

LW2846: 9600 dpi jpegs from original print purchased by Leon Worden. Color photo from Airport-Data.com. |

SEE ALSO: • Aircraft Down • 6-S Ranch Airpark, Canyon Country

Map 1930 Description 1940

Station, Glider Race, More, 1930-1947

Writer Devon Francis Goes Gliding 7-3-1941

Map 1946

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.