|

|

Rootin'tootin'ville, U.S.A.

Pageant magazine, May 1957.

|

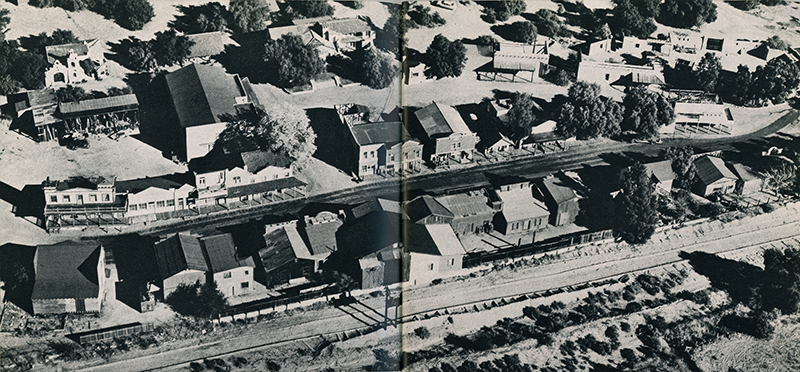

This aerial view of Melody Ranch appeared in the May 1957 edition of Pageant, a digest-format magazine that was published from 1944-1977 and attempted to compete with Reader's Digest. In the accompanying story, ranch owner Gene Autry discusses his plans to transform his Placerita Canyon property into a Western museum where visitors could see relics of bygone days and watch movies being made. Autry's plans literally went up in smoke in 1962. His dream did finally come true, though, (sans watching movie production) in 1988 — in L.A.'s Griffith Park.

Rootin'tootin'ville, U.S.A.

By Daniel Dixon | Pageant magazine Vol. 12 No. 11: May 1957.

LEATHERY OLD-TIMERS WHO go back that far unanimously agree that Cheyenne, Abilene, Tombstone and Dodge City were four of the most raucous trail-end towns ever to make a tenderfoot turn tail and scuttle back to the East. Obstreperous as they may have been, however, none of them were [sic] half as woolly as a little settlement out California way that goes by the innocent handle of Melody Ranch. This warped and wavering line of sun-baked wooden buildings has seen more banks robbed, more mining claims jumped, more range wars erupt, more dancing girls imported and more red-eye swilled than any ten Tombstones since the inventio of the six-shooter. Nowhere has the United States Cavalry put up so many gallant, lastditch stands. Nowhere have so many desperadoes been beaten to the draw. Nowhere have so many whooping redskins bitten the dust. Now, maybe you've never heard of Melody Ranch. But if you enjoy an occasional movie like "Johnny Concho," or if you're in the habit of watching television shows like "Gunsmoke," "Wyatt Earp," "Annie Oakley" or "Death Valley Days," you've certainly seen it — not once but dozens of times. Located 35 miles north of Los Angeles in a hot, hazy, boulder- strewn canyon, it's used to background many of the most popular horse operas that pop up on your TV or movie screen. Since 1915 [sic: 1936*], when the ranch was first opened for business, an endless string of shoot-em-ups have been cranked out on the premises. Very seldom during the 42 years that it's been in operation has the outfit been short of clients. Some companies show up for a single day's shooting, others stay six weeks. At one time or another, practically every lean-jawed, quick-handed movie cowboy from William S. Hart to Gary Cooper has galloped through his chores at the ranch**, and practically every myth, legend and romance of the Old West has come in for a manhandling. Not necessarily in this order, and almost never sticking to the strict historical facts, such stars as Harry Carey, Torn Mix, Buck Jones, Hoot Gibson, Gene Autry, Joel McCrea, John Wayne, Roy Rogers, Randolph Scott and Hopalong Cassidy have portrayed the virtues and villainies of Kit Carson, Billy the Kid, the James Boys, Wyatt Earp, Buffalo Bill, Bat Masterson, Wild Bill Hickok, and many others. More than 20,000,000 feet of film enough to stretch all the way across the country and half-way back again — have been spun through the cameras. One TV company alone, while turning out 350 different features, has exposed 4,000,000 feet of film here in the last four years. The false-fronted frontier settlement, though the most in demand, isn't the only attraction of the ranch. Also offered are two other villages, both of them complete in almost every detail. One is Spanish — adobe huts, hacienda, and fortress. The other is Indian — teepees, wickiups, and ceremonial grounds. These facilities are only a few yards from each other, but they have been so artfully positioned that as many as four companies can shoot on the ranch at the same time. As a result of the congestion, though, trouble sometimes busts loose. Not long ago, for instance, the lips of one hero were descending toward those of his heroine during a "Wyatt Earp" TV filming. In the background glowed a sunset. Murmured he, in his deepest, most romantic chest tones, "Honey, our troubles are over at last. The fighting is done. Now we can live in peace and quiet—" That was as far as he got. Just then, as if on cue, the whole scene was ripped to shreds by a deafening burst of gunfire from an adjoining set where an "Annie Oakley" episode was being made. Another time, the script of a picture called for a pair of runaway horses to thunder wildly down the street. Just to make sure that the animals were properly worked up, the director ordered a volley of rifles to be fired off into the air. The strategy worked — too well, as things turned out. The two horses, their eyes rolling with terror, their nostrils flecked with foam, stampeded through every production on the lot, before they were finally controlled. All in all, Melody Ranch is 50 acres in size. Back in the hills, there are precipitous roads along which stage coaches careen, enormous rocks from behind which posses and outlaws snipe at each other, canyons and gullies among which pursuers are lost. And down on the floor of the valley is a sandy stretch of terrain, inhospitable enough to be described as "a burning desert." The property contains a total of 72 buildings, most of them grouped together in one clump. In order to keep the public from becoming too familiar with the layout, the houses and stores are frequently repainted and the signs shifted around so that, just as an example, the assay office and the dressmaker's shop exchange places. Inside, only a few of the buildings are regularly used as sets and sound stages. Except for the three log cabins that have been converted into living quarters, the rest are employed as warehouses jammed from floor to ceiling with an indescribable assortment of relics, antiques, and just plain junk. Amid this mass of stuff can be found almost every implement, utensil, knick-knack and doo-dad ever used on old Western ranches. The supplies seem to be endless. From them it is possible to outfit, with almost faultless authenticity, a wagon train, a troop of cavalry, a posse or a tribe of Indians. That isn't all. In some of the outer buildings, there's an eye-popping batch of horse-drawn vehicles — surreys, prairie schooners, stage coaches, traps, chuck wagons. There's a number of bright-red fire engines, gleaming with polish, some of them dating all the way back to 1875. There are even a couple of solemn, black, velvet-curtained hearses, which the present owner of the ranch, actor Gene Autry, picked up in New England. Autry's latest, most impressive, and certainly most expensive acquisition is nothing more or less than an honest-to-Pete locomotive. Purchased from the Denver and Rio Grande a few months ago, the testy old veteran spent the years between 1890 and 1930 chuffing up and down the steep slopes of the Rockies. Back in the early days, the ranch belonged to a famous Western artist named Ernie Hickson, many of whose paintings are still on display around the place. It was Hickson's idea to build the town and rent it out as a unit to the nearby motion picture companies. From the start, his venture turned out to be a sound commercial proposition. After Hickson's death, his widow leased the property to Monogram Studios. It changed hands for good in 1952, when Gene Autry,_ who had just then entered television in a big way, was scouting around for a spot in which to film his epics. Autry is well known as one of the canniest — and one of the richest — businessmen in the world of entertainment, and one look was all he needed to see that the ranch suited his requirements. At this point, the first inventory taken in many years was conducted. It was a staggering task. John Brousseau, the manager of the ranch, pawed and sneezed his way through a mountain of articles that ranged all the way from a solid gold toothpick to a 1907 edition of an International automobile, smothered under a thick blanket of dust but miraculously in perfect running condition. Brousseau worked on the inventory for nearly three months before he was finished, and his list of the items on hand, when finally compiled, ran to 120 pages of singlespaced typewritten entries. Today, only Brousseau and Eddie Hogan, Autry's horse wrangler, live permanently on the premises. Now and then, the star of a picture currently before the cameras will hole up in one of the cabins, thus saving himself the time and trouble it would take to jockey back and forth between the ranch and town. Last year, for instance, Bill Boyd — better known as Hopalong Cassidy — dug in for three months, during which time he managed to grind out no less than 52 of the features in which he stars. Other than people like these, nobody sets up housekeeping at the ranch, though some character actors have spent so much of their professional lives around the place that it's become almost like home. Autry himself, whenever he can wrench loose from his backbreaking schedule of personal appearances and picture-making, uses the ranch as a retreat. "It's a good place to slow down," he says. "Out here, once in a while, I get a chance to sit under a tree and whittle. To me, that's pure pleasure. Then again, here's where I work out my horses. Both Champion and Little Champ got all their stage training on the ranch. In any case," he continues, "I guess I've got a sentimental attachment to the place. The first picture I ever made for Republic, "Tumblin' Tumbleweeds," was shot here back in 1934***. Brother, time sure switches things around! Who would ever have thought that 20 years later I'd wind up owning the street where I started?" Sooner or later, Autry plans to turn Melody Ranch into a huge Western museum. "I've got something here," he insists, "that ought to be preserved. Not enough people, these days, ever get a chance to see what the Old West was really like. That's why I'd like to build up the ranch. I want to make it as complete and as authentic as I can, and then open it to the public." Would such a museum cut down on the number of pictures produced at the ranch? "No," Autry says, "I don't think so. In fact, pictures would be part of the attraction. People like to see how movies are made. However, the main thing would have to be the museum. I don't know whether the idea will go over or not, but I'm sure going to give it a try." As a reality, Autry's museum is a few years off. By his own admission, thousands of articles have yet to be collected and thousands upon thousands of dollars invested. In the meantime, life at the ranch goes on as usual. A girl is kidnaped. There's a blast of gunfire, a clatter of hooves, a warning gritted out from behind a cigarette … "Smile when you say that, pod-nuh!" * Although he made movies in the Santa Clarita Valley as early as the mid-1920s, Trem Carr established his movie ranch in 1931 at the later location of Disney's Golden Oak Ranch. In 1936 he moved it down the road to property newly purchased by Ernie Hickson, which would become Melody Ranch. ** Not William S. Hart, although he may have used the general vicinity. Hart's last picture was released in 1925. *** Actually, "Tumblin' Tumbleweeds" (Republic 1935) used the original Trem Carr Pictures Ranch mentioned above. See Scheider 2011: 458-470.

LW2924: pdf from original magazine purchased 2017 by Leon Worden.

|

Brochure 1950s

Aerial & Story 1957

Train Collection

Main Street

Mexican Chapel

Buildings Late 1950s

Hacienda ~1962

Hoppy Invitation 1953

Champion Comic Cover (1955) Signed by Artist

Adventures of Champion at Vasquez Rocks 1955/56

Wichita 1955 (Mult.)

Man From Del Rio 1956 (Mult.)

Gunsmoke 1956

Gunfighters of Abilene, 1960 (Mult.)

Soraya, Ex-Queen of Iran, 1960

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.