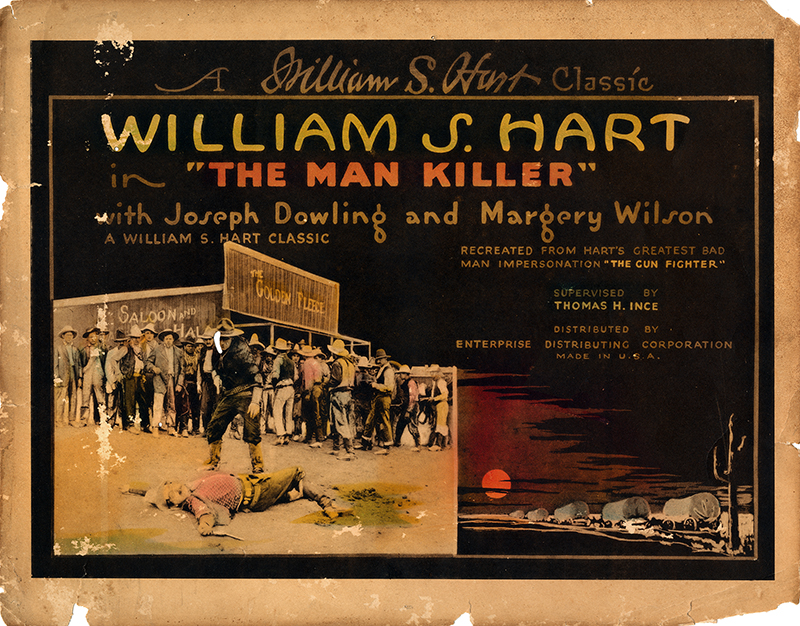

"The Man Killer" ("The Gun Fighter")

Starring William S. Hart

Click image to enlarge

| Download archival scan

William S. Hart never made a movie called "The Man Killer." He made a movie called "The Gun Fighter" for Thomas Ince at Triangle Film Corp. in 1916 (released 1917). A half-dozen years later, Stephen A. Lynch re-edited it, retitled it and re-released it in the southeastern United States as "a William S. Hart classic" through one of his corporate entities, Enterprise Distributing Corporation of Atlanta. A millionaire, Lynch made a fortune off the re-release of Triangle's old film stock. Bill Hart never saw a dime from it. There were no residuals back then, and the idea of actors trademarking their likeness or reserving their publicity rights was unthought-of. And besides, who in the 1910s could know there'd be an aftermarket for movies people had already seen?

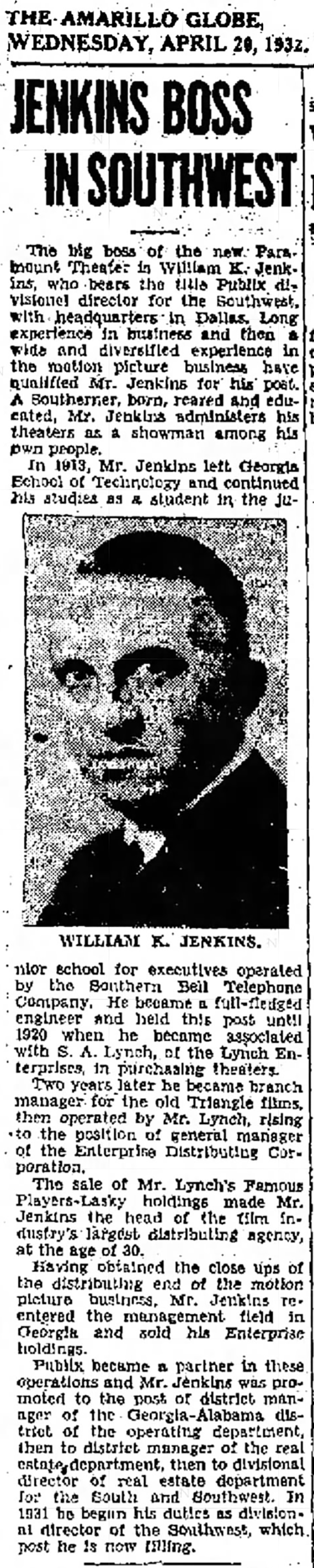

(T)he industry regarded the shelf life of its product to be a mere five years, and vaults were periodically cleared of films no longer held to be of value. Most were callously destroyed, as one would burn the Sunday paper after reading it. (Lahue 1971:174.) An estimated 75-76 percent of all silent films are lost forever for this and other reasons — but mostly for this reason. S.A. Lynch Enterprises Triangle boss Harry E. Aitken must have thought he got the better of the deal when he spun off his distribution wing and found a sucker in the person of Stephen Lynch to invest in it. Aitken needed cash to finance the production of new pictures, and here was some easy capital. Lynch (1882-1969) had played baseball in North Carolina, published newspapers in Florida, made money in the stock market and bought up so many movie theaters in the South that he was able to finagle an exclusive distribution deal with Paramount (then a distributor, not a production company) by the time he took over Triangle Distributing in 1917. The joke was on Harry Aitken when Lynch, now in charge of booking theaters under contract with Triangle as well as his own theaters in the South, began pressuring Aitken to meet the agreed-upon two-picture-per-week output — and for his share of the profits. Aitken filled the production gap by re-releasing some of Triangle's old Hart and Douglas Fairbanks pictures at cut rates, cheapening Triangle's top-flight brand. Lynch was pushed out of Triangle in 1919, but he retained his rights to distribute Triangle's old film stock in the South under his own corporate name, S.A. Lynch Enterprises Inc. (and regional affiliates such as Enterprise Distributing Corporation). By this time, it was clear there indeed was an aftermarket for movies people had already seen — because the truth is, most people actually hadn't seen them. Most of rural America had never seen a William S. Hart film. Or a Douglas Fairbanks film. Or a Charlie Chaplin film. Or a film starring any other Triangle contract player.

(I)nitial Triangle release was limited to the Triangle contract theaters, some 1,500 of the estimated 20,000 [total theaters] in operation during 1915-16, or less than 10 percent of the potential market. Most of these were located in the densely populated urban centers, for rural areas could not support the luxury of Triangle's "high-class" entertainment. Even Triangle's own reissue of its subjects reached less than 15 percent of the total exhibition outlets, leaving a huge number of theaters which had never played a single Triangle film. (Ibid.:177.) Sometimes Lynch's people would re-edit and retitle the pictures on re-release, sometimes not; in no case did the actors or directors or camera operators or anyone else on the production side receive any payment for their reissued work because they'd been paid wages or a salary under contract when the movie was made years earlier. Period. Ironically, it probably wasn't Lynch who was first to realize the value of re-releasing old Triangle pictures. It was Harry E. Aitken. W.H. Productions Harry Aitken was no victim, by any stretch of the imagination. Triangle historian Kalton C. Lahue describes him in terms usually reserved for a mob boss in his 1971 book, "Dreams for Sale: The Rise and Fall of the Triangle Film Corporation." In the fall of 1917, Aitken had the audacity to form two corporations that would make the reissue of old motion pictures a profitable business. Audacious, because Aitken named one of the distribution companies "W.H. Productions."

(P)redictably, patrons and exhibitors associated "W.H." with William S. Hart, parting with their money to see what they presumed to be new Bill Hart westerns. A loud hue and cry soon arose from disgruntled audiences. (Ibid.:174.) They weren't new pictures; they were old pictures, re-cut and given new names to fool the public. (Between Aitken and Lynch, this explains why there are different versions of certain Hart films today, with different runtimes.) Rival distribution companies filed complaints with the Federal Trade Commission, and the real "W.H.," who had just moved over to Adolph Zukor's Artcraft Pictures, sued. Neither legal action bore much fruit. When the FTC came calling, Aitken's companies, W.H. Productions and Tower Film Corporation, agreed to include the original name of the movies they retitled, both on title cards and in advertising — usually in teeny-tiny lettering. And that was about it. (Note that Stephen A. Lynch did this when he released "The Man Killer" in 1923 and 1924: Fine print on the lobby card reads, "Recreated from Hart's greatest bad man impersonation, 'The Gun Fighter.'") Tower and W.H. Productions made a ton of money for Harry Aitken.

Both of these organizations acquired rights to a large block of Triangle negatives, which included the Keystone, Reliance, Majestic and Ince films of the Mutual period (1912-15), as well as early Triangle productions, for less than $100,000 total payment. The negatives were recut, retitled (in some cases) and reissued on the independent market ... grossing an undetermined but fantastic sum, generally agreed upon by those involved as being well in excess of $1 million. (Ibid.:192-193.) Postscript. The true figure, according to author Lahue, probably exceeded $3 million by 1919, when Aitken was finally sidelined. "It was now apparent that Harry Aitken had managed to bilk Triangle out of $3 million at the very least in a little over three years" (ibid.). Triangle floundered for a few years and went broke; Aitken ultimately settled out of court for $1.375 million. For his part, Stephen A. Lynch "was at best an unsavory character" who maintained a "veil of secrecy" around his activities such that "his role in the various conspiracies which swirled about and around Triangle has not and probably never will come completely to light" (ibid.:201). The Federal Trade Commission eventually broke up the monopolistic production-distribution-exhibition chain. Movie studios and distributors can't own movie theaters today. And what of William S. Hart? He never got over his loathing of studio bosses who corrupted the art form he loved and denied him the earnings he felt he was due. Unlucky in love, his short-lived marriage produced a son who didn't grow up under his roof. The only people who never betrayed him were his fans — so he left them most of his worldly possessions including his house in Hollywood and his hilltop mansion in Newhall.

LW3643: 9600 dpi jpeg from original lobby card purchased 2019 by Leon Worden.

|