Remains of 2 Ancient Bison Found in Castaic Oil Fields.

|

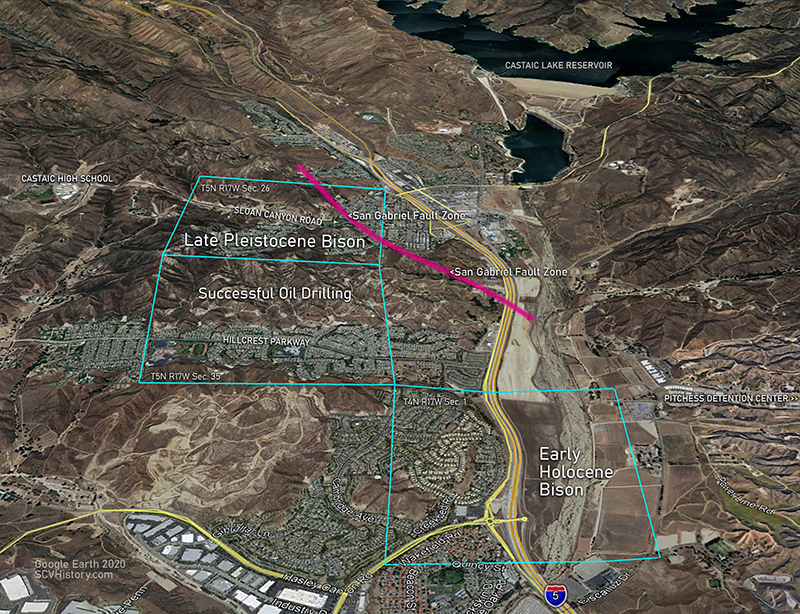

Teeth and bone discovered at two locations in the Castaic area were determined by the chief curator of the (now) L.A. County Natural History Museum to have come from a pair of late Pleistocene or early Holocene bison, i.e., from either side of about 11,700 years ago, when most of the Ice Age glaciers had receded. The discoveries were made in 1950 by William Henry Corey (1901-1979), a professional, U.C. Berkeley-trained geologist who was hired to tell the Continental Oil Company where to dig. The two sets of remains were found in fairly close proximity to one another, one just west of today's I-5 Freeway around Sloan Canyon Road, and the other a bit to the southeast in the alluvial sands of Castaic Creek. In his master's thesis on the geology of the Castaic area, Leonard T. Stitt describes the former (Sloan Canyon) as lying in the Pleistocene-age Pico formation "near the San Gabriel fault zone" in Section 26 of Township 5N, Range 17W. This is the top blue box on the map above. The latter (Castaic Creek) he describes as lying in a stratum of older alluvium — sand and gravel — in Section 1 of Township 4N, Range 17W. This is the bottom blue box on the map above.

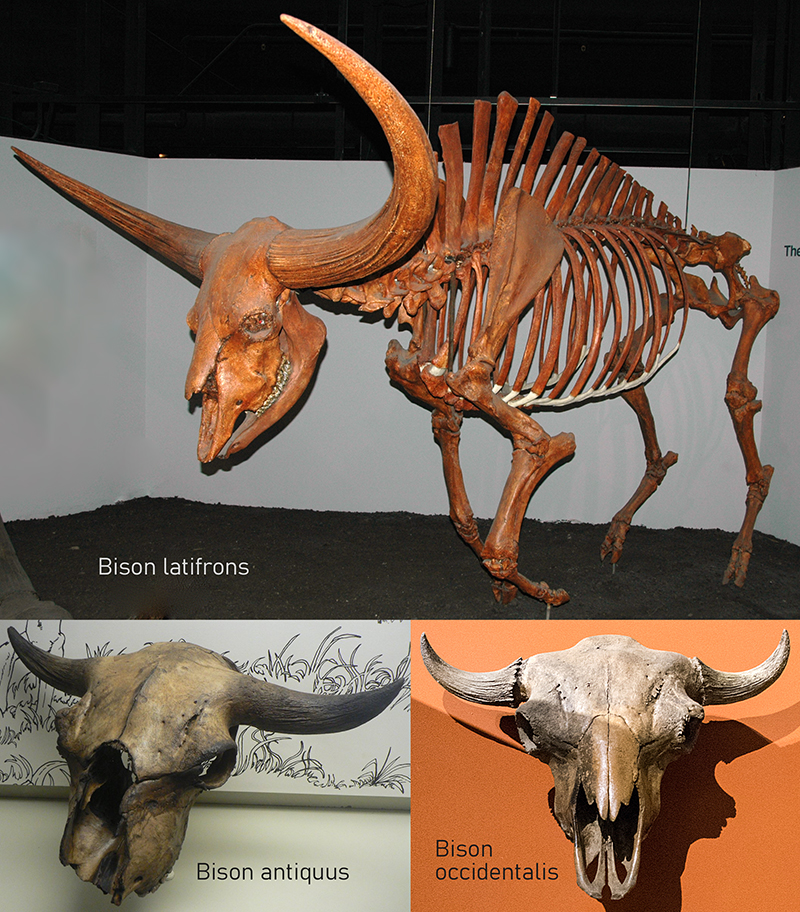

In a previous professional paper written in the 1950s for the U.S. Geological Survey (published 1962), USGS staff geologists Edward L. "Jerry" Winterer and D.L. Durham discuss a personal conversation one of them had with the discoverer, Corey, in 1951. As to the potentially older bison from the Sloan Canyon Road vicinity, Corey told them the remains consisted of a "jawbone and teeth" that were found in "reddish-brown clay beds near a large fault." The second bison remains consisted of "a bison tooth (which) was collected by Corey at an outcrop near the junction of Castaic Creek and the Santa Clara River." Fossils in Motion. Seismic and alluvial activity in the area causes overlapping geological formations to shift over time. It can be difficult to know exactly where — and when — a fossil was originally deposited. Corey initially thought the — let's call it the Sloan Canyon bison — remains were embedded in the Plio-Pleistocene Saugus formation, which would make it older, potentially much older, than 11,700 years. However, when Corey showed them to Chester Stock, chief curator of science at the L.A. County Museum and co-founder of the Geology Department at Caltech, "Stock examined the material and told him that the bison is a very late one, possibly even Recent," aka Holocene, which started 11,700 years ago. (Stock died in 1950, which fact pinpoints the discovery year.) Winterer and Durham speculate: "It may be that the dipping beds do not belong to the Saugus formation but are stream-terrace deposits of late Pleistocene age that were deformed during movements along the nearby fault. If, on the contrary, the beds containing bison are within the Saugus formation, then the age range of that formation must be extended at least into the late Pleistocene." In other words, either they're from the Pico formation, or everybody's wrong about the age of the Saugus formation. As noted, Stitt (1981), relying in part on an unpublished thesis paper by a UCLA grad student (Pollard 1958), assigns the Sloan Canyon fossils to the Pico formation and posits: "(The) remains of a Pleistocene bison ... may have been deposited in the Saugus formation or in terrace material which has since been disrupted by movement on the San Gabriel fault." The tooth from the "younger" bison — let's call it the Castaic Creek bison — was determined by Chester Stock to belong "to a very late Pleistocene or even Recent [Holocene] bison" (Winterer & Durham 1962). Stitt (1981) refers to it as "a bison of possible Holocene age." Corey, the discoverer, told Winterer and/or Durham that "the tooth was collected at the surface of the Saugus [formation] outcrop," and he "could not be certain whether the tooth came from the Saugus formation or was washed from the overlying terrace gravel." The upshot? The "Sloan Canyon" bison probably died a little earlier than 11,700 years ago. The "Castaic Creek" bison probably died a little later than 11,700 years ago — when North America was too warm for giant bison and mastodons and other large, thick-coated mammals but warm enough for hairless, two-legged creatures to begin to live longer and multiply in greater numbers.

About the Discoverer, William Henry Corey.

By Philip R. Patten For more than forty years, until the onset of a long illness, William Henry Corey was a gifted and enthusiastic worker in the geology of California and the West. With his death, October 15, 1979, many of us lost a valued friend and an amiable, though demanding, colleague. An alumnus of the University of California (Berkeley), he was a member of Theta Tau, Sigma Xi, the American Association of Petroleum Geologists (Emeritus), the Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists, and a Fellow of the Geological Society of America. He is survived by his wife, Marilyn, a son, a daughter, five grandchildren, and one great-grandson. Bill was born in Chattanooga, Tennessee, January 23, 1901, but spent his early school years in Southern California. After graduation from Polytechnic High School in Long Beach, California, he received a practical introduction to the oil industry before entering college. For two years he worked in the oil fields as roustabout, tool dresser and roughneck. After his undergraduate studies at the University of California at Los Angeles and at Berkeley, he received his master's degree in geology from Berkeley in 1928. His study of the Oligocene and lower Miocene formations of coastal California, begun at this time, was to continue through many years. Before completion of his doctoral requirements, he was called away from Berkeley for family reasons. It is a measure of Bill's quality as a geologist that he was able to obtain full-time professional employment in 1930, at the depth of a major economic depression. While he was with the Standard Oil Company of California, he spent three years as field geologist on the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, Mexico, then returned to the Los Angeles basin, assigned to field and subsurface mapping. In 1937, he was employed by the Shell Oil Company as a field party chief in Venezuela, mapping in the northwest margin of the Andes and in the Apure River basin. In 1942, after two years as an independent geologist, Bill joined the Continental Oil Company as a senior geologist. Based in Los Angeles, his assignments ranged throughout California as well as the adjacent states and Alaska. As early as 1948, he served with the CUSS group (Continental Union, Shell, Superior) and participated in some of the first significant industry exploration of offshore California. While supervising geological field crews in Nevada, Bill easily adapted to the Paleozoic stratigraphy. Where necessary he devised his own sequences, and for the most part these remain compatible with today's state of the art. Within a few months, he had personally reconnoitered most of the eastern half of Nevada, much of the time by himself with the most rudimentary base maps. His knack for the discovery of critical outcrops, often obscure and nearly inaccessible, under these conditions is still impressive in these days of helicopter geology. In 1962, he retired from Continental as Regional Research Geologist and began work as an independent geologist. He continued as an active consultant until ill health forced an end to a long and productive career. Bill's lifelong interest in faulting and the lower Tertiary stratigraphy of California led to numerous publications and society talks on these subjects. Although always an avid student of geologic literature, his concepts were based in large part upon years of personal observations of field relationships and subsurface data. He believed that geology on a regional scale, even hemisphere-wide, was essential to petroleum exploration, and he always insisted that he was primarily a practical explorationist and an oil finder. Certainly, he contributed to, or anticipated, many oil discoveries. He enjoyed travel with his family, especially to Mexico, to which he often returned. Wherever he went, he was keenly interested in the land as well as the geology. Despite his pace in the field, he always found time to reward his companions with his knowledge of the work life, local customs, and the traces of history.

|