California's Oldest Well.

First commercially successful well in State dedicated in Pico Canyon by pioneer oil men.

|

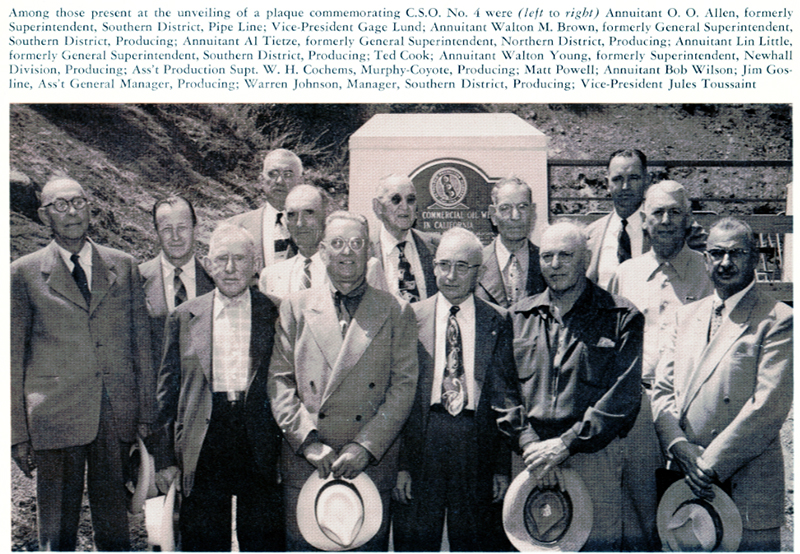

About four miles — as a crow would fly — from Route 99, one of the busiest highways in the United States, a group of men assembled recently to dedicate a small plaque, 22 by 36 inches. Back there in the dense undergrowth of Pico Canyon there didn't seem to be any connection between the smoothly pumping "grasshopper" on C.S.O. No. 4 and the stream of vehicles pouring over the "Grapevine." But to the gathering of the Petroleum Production Pioneers, the traffic was definitely of related interest. For C.S.O. No. 4 was the first commercially successful oil well completed in California ... by the California Star Oil Works Company, a predecessor of ours. That was back in September 1876 — the well was then called Pico No. 4 — yet old faithful is still producing its regular 30 barrels per month. The plaque was inscribed in part: "It was not only the discovery well of the Newhall Field but was indeed a powerful stimulus to the subsequent development of the California petroleum industry." The men who heard this dedication were just what their organization's name describes them to be — petroleum pioneers — senior members of which had been in the producing end of the oil game at least 30 years. But up there on the windswept Santa Susanas, the range of mountains at the northern end of the San Fernando Valley, the plaque was a commemorative symbol of the real pioneers of the West Coast petroleum industry. Those men who had the courage to continue drilling after three holes were abandoned, back in the years when "coal oil" and axle grease were about the only two products of value. D.G. Scofield and C.A. Mentry started drilling in Pico Canyon in 1875.

The dedication of the plaque was conducted by Petroleum Pioneers' president, B.H. Anderson of the Continental Oil, and Paul Andrews of Signal Oil and Gas, Pioneers' historian. Andrews traced some of the background and aims of the organization in perpetuating important historical events and milestones in the petroleum industry. In the crowd of a couple of hundred people who turned out were several Standard Oilers, including vice presidents Gage Lund and Jules Toussaint. Toussaint traced the interesting background of the well itself, the history of the Pico Canyon area, and many of the people who participated in the early drilling and development work. He also pointed out that, like most people everywhere, the greatest interest in tracing an historical event lies in the people themselves — those who actually performed the deeds. He talked about Scofield, and also reviewed some of the early history of our company. Scofield was a young geologist from the Pennsylvania oil fields who had come to San Francisco to enter the marketing end of this new business. But when he heard of the oil seepage near Newhall, he headed south and acquired acreage in the well-nigh inaccessible Pico Canyon. Alex Mentry was a Los Angeles carpenter, powerful and bearded. All the materials had to be taken in over crude trails by wagon and sled. Snubbing posts were necessary and helpful since later drilling was done both in the canyons and on top of the 2000-foot ridges. Bull wheels and calf wheels, the boilers and drill stems, casing and rope — all were lugged laboriously up hill and down dale. Rattlesnakes and wasps, mud and underbrush — all had to be contended with.

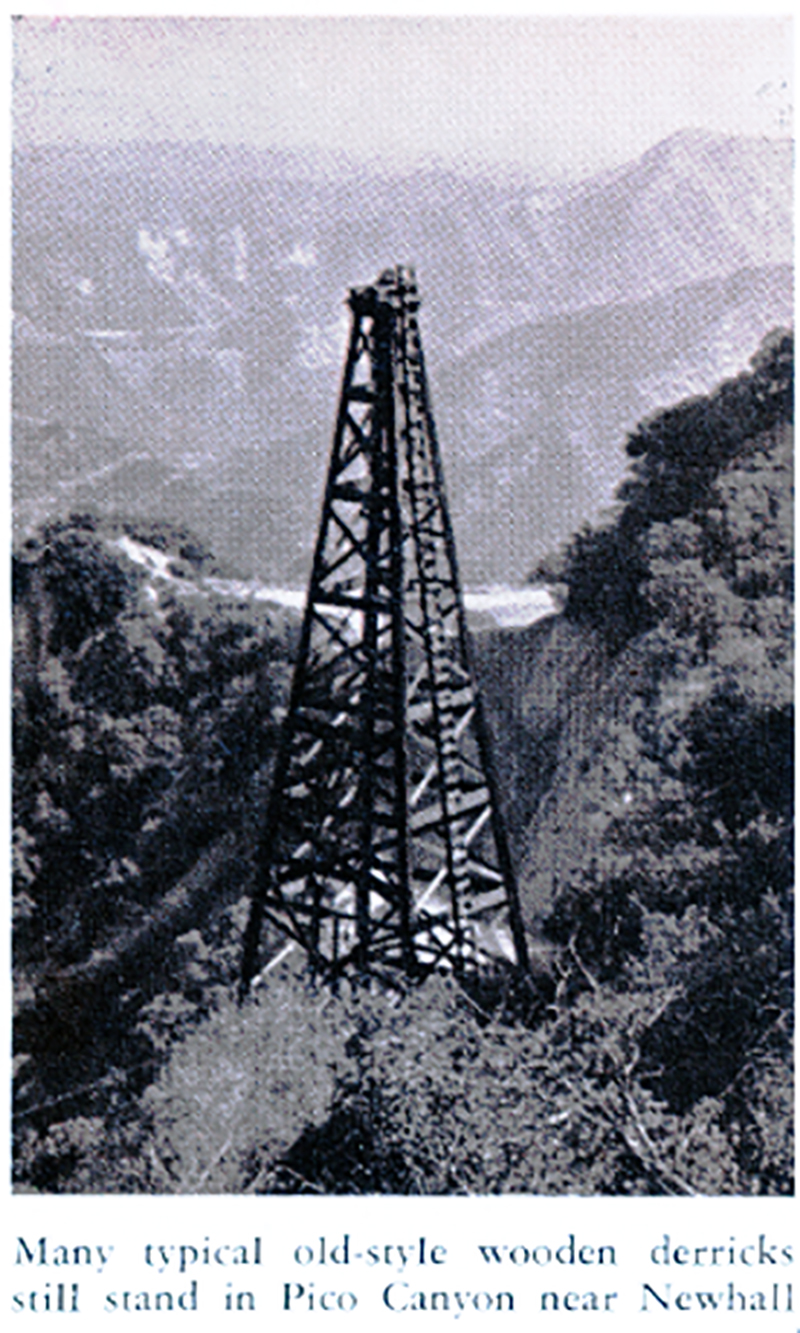

They used the primitive spring pole method of drilling. In this, the weight of two men was the force that sent the bit into the ground, and the springy strength of a sapling raised it out again for the next stroke. It took them a month to drill the first well, C.S.O. No. l (Pico No. 1), to a depth of 120 feet where 11 barrels a day of 32 gravity oil were recovered. But it was abandoned because of the small flow. C.S.O. No. 2 was the same sort of producer, and it, too, was abandoned. The third hole was dry. A steam engine was brought in and the fourth hole was taken to the prodigious depth of 300 feet. There, on September 26, 1876, 77 years ago next month, C.S.O. No. 4 was completed for 30 barrels a day and a fair amount of gas. Soon, squat 30-foot wooden derricks sprouted all through the canyons and ridges of the territory. Now the problem of refining the oil into kerosene and benzene came up. But Scofield had foresightedly built a three-still refinery at Newhall, six miles southeast — the first practical commercial refinery in the state — and another at Ventura (then called San Buenaventura). Together they had a capacity of 60 barrels a day. The crude oil was transported by horse and wagon over the rough trails to the refineries. Then came the problem of how to get the product to market. The railroad had not been finished yet, and the only way to market was by wagon over the mountains to San Pedro or Ventura and thence to San Francisco by sailing ship.

In 1879, the Pacific Coast Oil Co. was founded with the California Star Oil Works continuing as a subsidiary. (Our present company evolved from Pacific Coast, Scofield becoming Standard's first president.) A two-inch pipe line (the state's first) was laid to Elayon, the nearest stop to Pico on the newly completed railroad. There the oil was loaded on tank cars — flat cars on which two upright oil tanks were awkwardly mounted — for shipment to a new refinery at Alameda Point on San Francisco Bay. Later a pipe line was laid to Ventura, and the steam tanker George Loomis was built. The Loomis was the pioneer of our fleet — the first steel oil tanker built on the Pacific Coast, and the second in the United States. Reliance on sails was not entirely eliminated, as she had two masts. The 6400-barrel cargo carried in her tanks had not yet been successfully used as ship's fuel, although experiments were underway. This forerunner of our modern tanker fleet was named for one of our early shareholders. Tragically, the Loomis was later lost at sea with all hands aboard.

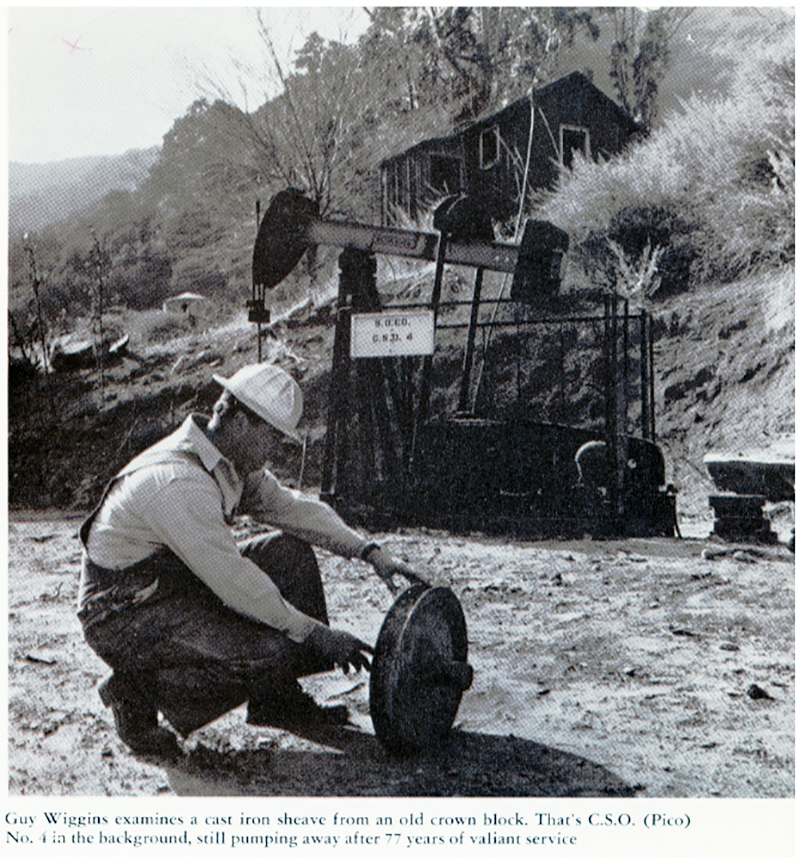

(Several years ago the old refinery just west of Newhall was reconstructed as a monument to the pioneers who had built and operated it.) Today there are 41 wells in Pico Canyon: 11 are on steady production, and 30 are shut-in for various reasons. In 1879, C.S.O. No. 4 was deepened to 1400 feet (where 150 barrels a day were recovered) and converted to a pumping well. Today it is producing from 18 to 45 barrels per month of 36.9 gravity oil. It is also making 350,000 cubic feet of gas per month. The wells are operated variously; some work off a jack — a central power plant from which long rods extend to pump the adjacent rigs. Others operate one another; and some that are particularly isolated are pumped by their individual engines. Production Relief Man Guy Wiggins is about the only man who wanders through this ancient segment of history today. Some of these wells are pumped for only a few hours a day. All around him he sees the remains of other oil men's heavy labors: the old steam plants that used to power the drilling, now red-rusted, with stacks prone; a small hand forge; a few rotting, wooden shacks. Guy has one thing in common with those first employees: He, too, must carry a heavy stick and keep his eyes open for rattlesnakes. Seventy-eight years have seen little change in Pico Canyon. The short, squat derricks are symbols of the past. But Guy's pickup truck is evidence of the revolution caused by these very same wells. A revolution that helped open up California and the West and epitomizes our company's promise: "Standard plans ahead to serve you better."

Download individual pages here.

|