|

|

Dissecting the Dream: Fact, Fiction, and Placerita's Golden Oak.

By Alan Pollack, M.D.

| Heritage Junction Dispatch, November-December 2015.

|

[ Watch the extended video version]

Was the story of the Oak of the Golden Dream fact or legend? Let's examine the evidence available to us. As the story goes, on March 9, 1842, forty-year-old Jose Francisco de Gracia Lopez, more commonly known as Francisco Lopez, foreman of the Rancho San Francisco, and two of his coworkers, Manuel Cota and Domingo Bermudez, wandered into the Canon de los Encinos (Canyon of the Oaks), now thought to be Placerita Canyon, in search of some stray cattle. Needing some rest on a hot day, Lopez fell asleep under an old oak tree and dreamed of finding gold.

A short time later, Lopez sent a letter to California Gov. Juan B. Alvarado, notifying him of the gold discovery and seeking permission to mine the gold. Thus we have the first documented gold discovery in California history, fully six years prior to the more famous discovery of gold by John Marshall in John Sutter's millrace on the south fork of the American River. The oak tree under which Lopez presumably fell asleep is now referred to as the Oak of the Golden Dream. But is this what really happened? Earliest Mentions of Gold in California Gold had presumably been found in California and the Santa Clarita Valley, but not documented, even prior to the Lopez discovery. According to Guy J. Giffen in the March 1948 edition of the Historical Society of Southern California's "Quarterly" publication, a cleric accompanying Sir Francis Drake on his famous circumnavigation of the globe made note of a golden treasure to be found among the rocks on the California coast when the Drake expedition landed in California on June 17, 1579. Sebastián Vizcaíno sailed up the coast of Alta California (now Southern California) in November 1602 on a mission to find safe harbors for Spanish Manila galleons on their journey from Manila to Acapulco, and to map in detail the California coastline. He reported to the Spanish king about possibilities of gold in California. Russian explorers were said to be aware of gold in California in 1814. Mountain man Jedediah Smith was thought to have found gold near Mono Lake in 1825, which he took with him to the Green River camp of the American Fur Co. Eugène Duflot de Mofras, a French naturalist, botanist, diplomat and explorer, was sent to explore the Pacific Coast of North America from 1840-1842, ostensibly to access the Mexican Alta California and American Oregon Territory regions for French business interests. In his records, he mentions the discovery of gold at San Isidro in present-day San Diego County in 1828.

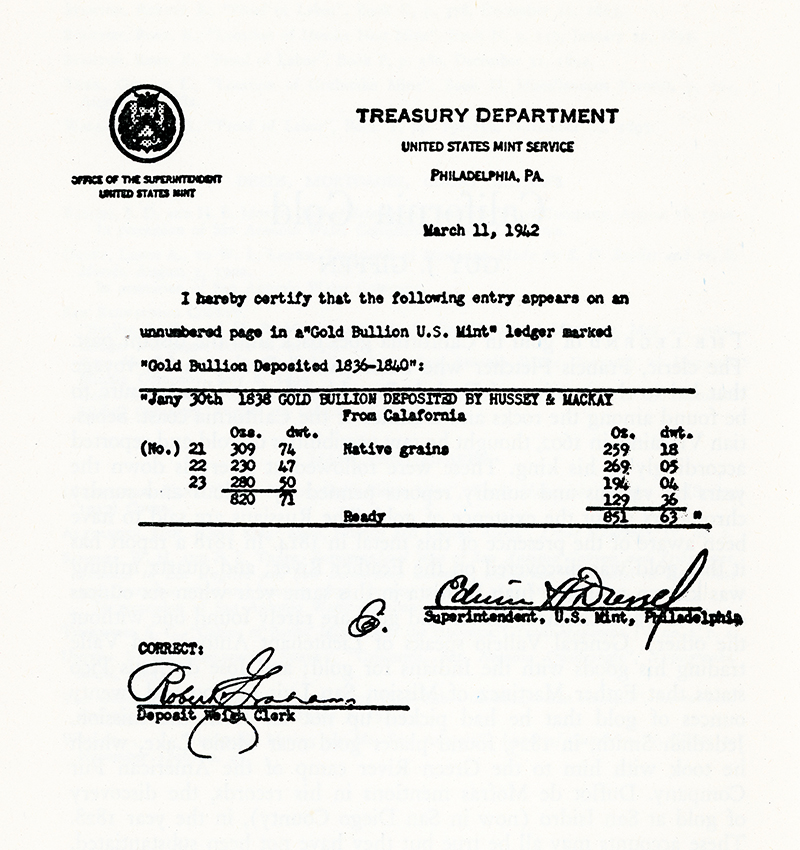

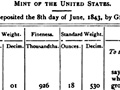

Giffen also mentions an interesting document from the Philadelphia Mint that shows the first shipment of California gold to the mint by the firm of Hussey and Mackay on Jan. 30, 1838. The firm handed in 851 ounces, 63 dwt (pennyweight) of California native grains — placer gold — worth approximately $16,000. Giffen writes: "Just how this firm came into possession of these grains has not been determined. A letter from Mabel Gillis, librarian of the California State Library, may throw some light on the subject. One Thomas McKay was an employee of the Hudson (sic) Bay Company. He trapped in the Klamath country, Northern California, as early as 1825 and was in and out of California for a number of years, returning to Vancouver in 1838. In the will of the New York George Mackay he mentions a brother T.R. Mackay, who might or might not have been the Thomas McKay of the Hudson Bay Company. In spite of the difference in the spelling of the name, one might conjecture that he was the relative of the New York broker, and that the gold was sent to him by his brother." In the Santa Clarita Valley, there is the legend of the Lost Padres Mine, a story of a cache of gold that may have been buried by the priests of the San Fernando Mission in the 1790s. To this day, no one has found a trace of this gold. There are also reports of gold mining in San Francisquito Canyon in the 1820s and ‘30s. Lopez Family Genealogy According to José Jesús López, a grandnephew of Francisco Lopez, in a 1916 interview with author Frank F. Latta ("Saga Of Rancho El Tejon," 1976), the ancestors of the Lopez family came from the Asturias province in Spain. The family was wealthy and belonged to the aristocracy of Castile. This is disputed by Lynn Adams, a descendant of Jose Ygnacio Maria de Jesus Lopez. Her genealogical research shows that the patriarch of the Lopez family in New Spain (Mexico) was Andres Lopez, born circa 1695 in Sinaloa. She speculates, although unsubstantiated, that the grandfather of Andres Lopez may have been a Juan Lopez who was a conquistador under Hernán Cortés. Jose Ygnacio Maria de Jesus López and his wife, María Facunda de Mora de López, brought the López family to Alta California, arriving from Baja California by about 1771. By order of the king of Spain, he would oversee the construction of the San Gabriel Mission. They started their journey in the mainland state of Michoacan, where they helped put down a revolution. As a reward for his service in Michoacan, one of their sons, Juan Bautista López, was appointed mayordomo (foreman) of the San Fernando Mission when it was built in 1797. Juan Bautista López and his wife María Dolores Salgado de López had a number of children, including Pedro Lopez, who became mayordomo of the San Fernando Mission after the missions were secularized in 1834. Another of their sons was the gold discoverer Francisco Lopez. Pedro's daughter (and Francisco's niece) Catalina Lopez married her second cousin, Jeronimo Lopez. They became the proprietors of Lopez Station, a stagecoach stop which they built around 1861. The site of Lopez Station later became the Van Norman Reservoir in Sylmar. They also built the Lopez Adobe in 1882, which still stands in the city of San Fernando.

The Life of Francisco Lopez

Francisco Lopez studied French in college in Mexico City and learned mineralogy at the Colegia de Mineria. When he came to the Rancho San Francisco, he spent time hunting for gold, bears, and mountain lions.

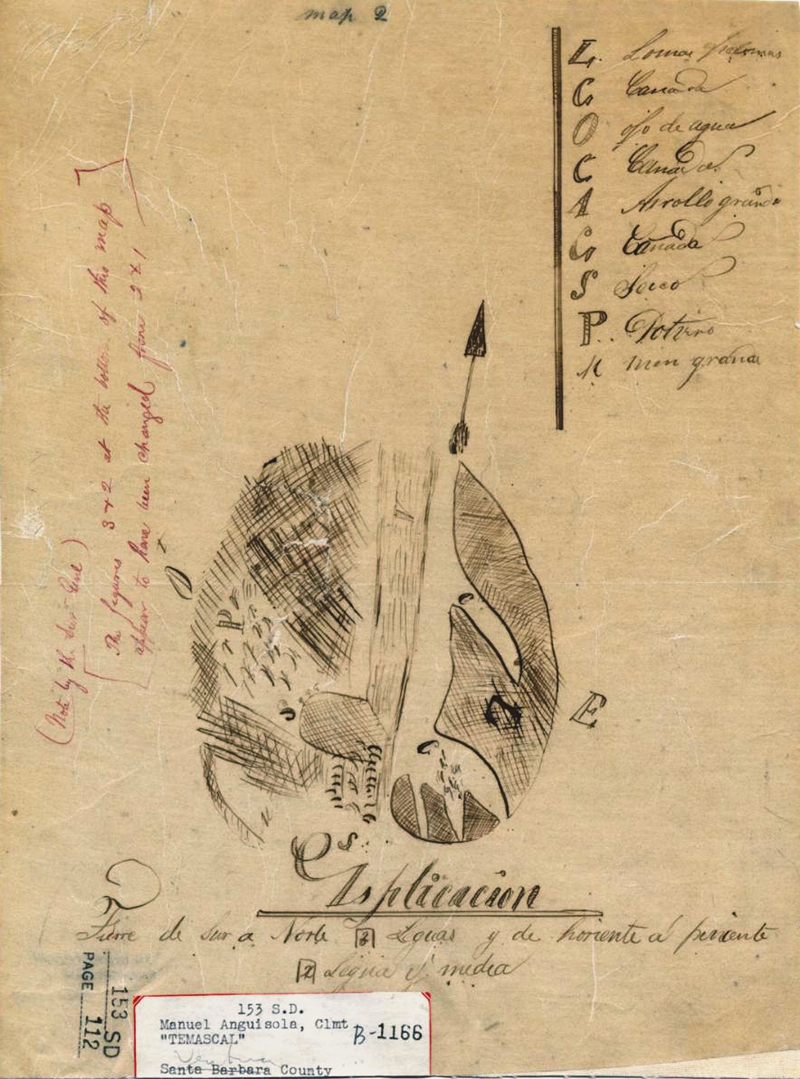

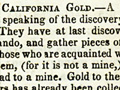

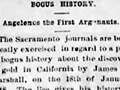

Maria Jacoba Feliz, the daughter of Jose Tomas Feliz and Maria de Jesus Lopez, ended up marrying Antonio Del Valle, the man who was granted the Rancho San Francisco (48,000 acres of the Santa Clarita Valley) by Governor Juan Alvarado in 1839. Prior to obtaining the land grant, Del Valle had taken over as mayordomo of the San Fernando Mission from Pedro Lopez in 1837. The Del Valles rented a portion of the rancho to Francisco Lopez, who used it for grazing cattle. Francisco would himself become a wealthy landowner. He and his brother Pedro were granted the Rancho Tujunga (now Lake View Terrace, Sunland and Tujunga) in 1840. They traded Tujunga for the Rancho Cahuenga in 1845. Francisco, along with Jose Arellanes, was granted the Rancho Temescal (Piru and Lake Piru to Hasley Canyon) in 1843. Finally in 1846, Francisco obtained yet another land grant (along with Luis Jordan and Vicente Botiller) — the Rancho Los Alamos y Agua Caliente. This later became part of the Tejon Ranch in Kern County. After obtaining the Rancho Temescal, Francisco found and mined gold in San Feliciana Canyon. Although some speculate this may have been the actual location of his 1842 gold discovery, other sources claim this to be a separate gold discovery from the one in Placerita Canyon. On Oct. 1, 1842, a brief article in the New York Observer newspaper announced the Placerita Canyon Gold discovery to the world: CALIFORNIA GOLD. — A letter from California, dated May 1, speaking of the discovery of gold in that country, says: — "They have at last discovered gold, not far from San Fernando, and gather pieces of the size of an eighth of a dollar. Those who are acquainted with these "placeres," as they call them, (for it is not a mine,) say it will grow richer, and may lead to a mine. Gold to the amount of some thousands of dollars has already been collected." Abel Stearns, 1867 Let's examine the sources of the Lopez gold discovery story. On July 6, 1867, Los Angeles merchant king Abel Stearns wrote a letter to Louis R. Lull, Esq., secretary of the Society of Pioneers, San Francisco, in which he related what Francisco Lopez had personally told him about the gold discovery: "The circumstances of the discovery by Lopez, as related by him, are as follows: Lopez with a companion, was out in search of some stray horses, and about midday they stopped under some trees and tied their horses out to feed, they resting under the shade; when Lopez with his sheath knife dug up some wild onions, and in the dirt discovered a piece of gold, and searching further found some more. He brought these to town and showed them to his friends, who at once declared there must be a placer of gold. This news being circulated; numbers of citizens went to the place and commenced prospecting in the neighborhood, and found it to be a fact that there was a placer of gold. After being satisfied many persons returned; some remained, particularly Sonorensee (Sonorians), who were accustomed to work in placers. They met with good success. From this time the placers were worked with more or less success, and principally by Sonorensee, until the latter part of 1846, when most of the Sonorensee left with Captain Flores for Sonora. "While worked there was some six or eight thousand dollars taken out per annum." Note that there is no mention of a golden dream or golden oak in this account. Stearns, upon receiving gold samples from the canyon, sent the samples on Nov. 22, 1842, to Alfred Robinson and asked that he take them to the United States Mint in Philadelphia to be assayed. Robinson wrote to Stearns from New York on Aug. 6, 1843:

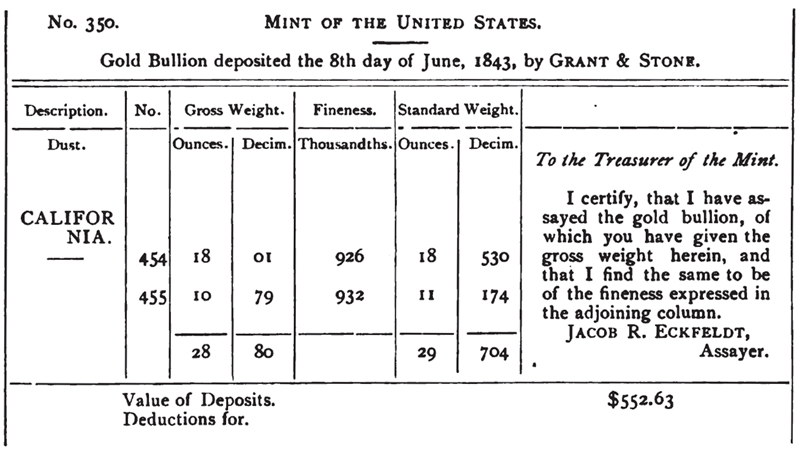

"My Dear D. Abel: I embrace this opportunity of the sailing of a ship from Boston to address you a few lines, and therein to inform you of the result of your shipment of gold, which is as follows, as per statement from the mint at Philadelphia: Memorandum of gold bullion deposited the 8th day of July, 1843, at the mint of the United States at Philadelphia, by Grant & Stone, of weight and value as follows: Before melting, 18 34-100 oz.; after melting, 19 1-100 oz.; fineness, 926-1000; value, $344.75; deduct expenses, sending to Philadelphia and agency there, $4.02; net $340.73." A voucher from the United States Mint dated June 8, 1843, was found in the office of the First Comptroller, Washington, D.C., in 1891, confirming the gold deposit mentioned by Robinson. John Murray, Overland Monthly, 1892 An article by John Murray in the Overland Monthly in May 1892 (Vol. XIX No. 113, Pp. 524-529) dated the Lopez gold discovery to 1841. Murray quoted from a pamphlet he had obtained, entitled "An Historical Sketch of Los Angeles County," published in 1876 by L.A. businessmen John J. Warner, Benjamin Hayes and J.P. Widney: "There is conclusive evidence that the first known grain of native gold dust was found upon, or near, the San Francisco Ranch, about forty-five miles westerly from Los Angeles city, in the month of June, 1841. "The discovery of this gold was, in a two-fold manner, accidental. Some time in the latter part of 1840, or the early part of 1841, a Mexican mineralogist, Don Andres Castillero, traveling from Los Angeles to Monterey, while passing along the road over the Las Virgenes Rancho, saw and gathered up some small water-worn mineralogical pebbles, known by Mexican placer miners as tepustete, — a variety of pyrites, — which he exhibited at the residence of Don José Antonio de la Guerra-y-Noriega, in Santa Barbara, where he was a guest; and stated that wherever these pebbles were found in place it was a good indication of placer gold fields. A Mr. Francisco Lopez, also known by the name of Cuso, a farmer and herdsman, living at the time upon the Piru Rancho, was present and heard the statement, and saw the pebbles. Not long after this incident, Mr. Lopez noticed a pebble similar to the one he had seen in the hands of Mr. Castillero; and remembering what was then said about its being a sign of gold, he scooped up a handful of the earth and, rubbing it in his hand, found a grain of gold. The news of this discovery soon spread among the inhabitants, from Santa Barbara to Los Angeles, and in a few weeks hundreds of people were engaged in washing and winnowing the sands and earth of these gold fields." Murray questioned the accuracy of the Abel Stearns account that dated the gold discovery to 1842: "Mr. H.H. Bancroft makes the date of discovery 1842, and so does Mr. Stearns. In a recent letter from Colonel Warner, which is now presented, he explains how Mr. Stearns could easily have been mistaken. The pamphlet also points out that Mr. Stearns, writing upon the subject after a lapse of twenty-five years, and a merchant at that time, would, upon referring to his books, be more likely to find the date of the purchase of gold than that of the discovery of the gold fields." The letter written Nov. 13, 1891, from Colonel J.J. Warner to Murray stated: "I arrived in Monterey, from a visit to New England, in June, 1841. I reached home in Los Angeles July 4th. ... Not long after my return home, I accompanied three or four men to the gold fields on the ranch of San Francisco, then owned by Antonio Del Valle. The men with whom I went were not residents, but visitors in Los Angeles, being owners, supercargoes, clerks, etc., of merchant vessels then trading on this coast. I do not remember (and have no notes to which I can refer) the month in which this visit was made. It was in the summer, or dry season, of the year. ... Mr. Bancroft asserts that the discovery of gold was made in 1842, and cites events and transactions to sustain the assertion; but the careful reader will observe that no one of the events he cites has any bearing upon, or connection with, the date of the discovery. ... In another place Mr. Bancroft says that the gold was discovered on the ranch of Antonio Del Valle during his lifetime. There is also, in one of his volumes, a biography of Mr. Del Valle, (probably furnished by his son, Don Ignacio Del Valle,) in which it is stated that Mr. Del Valle died in 1841. "Mr. Stearns could not have bought gold upon the day of the discovery, nor until the gold was mined and taken to market; and this might, or might not, have been until the lapse of one or more years from the time of discovery: so his purchases of gold, whether made in March, or some other month, have no weight in fixing the date of discovery." From this letter, Murray concluded: "Thus the date of the discovery is established as being 1841. The very limited circulation of the fact, even in the State itself, is warrant for this article." J.M. Guinn, San Francisco Call, 1895 In an article in the San Francisco Call newspaper of Sept. 8, 1895, J.M. Guinn, secretary of the Southern California Historical Society, summarized the controversy over the date of the Lopez gold discovery: "The time of the discovery is not so satisfactorily settled. Colonel Warner, usually very reliable, gives June 1841 as the date, and quotes Don Ygnacio del Valle, on whose rancho the discovery was made, and who was appointed encargado de justicia to preserve order in the mining district, as one of his authorities for that date. Don Abel Stearns gives us the date March 1842; Bandini, April 1842. (Antonio F.) Coronel, who spent some time in the mines and employed Indians in mining, asserts positively that it was made in 1842. Bancroft is contradictory in his dates. In the text of his history he gives March 1842, evidently following Stearns' statement. In his Pioneer Register he states: ‘Antonio del Valle died in 1841, the same year that gold was discovered on his ranch.' ... William Heath Davis, usually one of the most reliable chroniclers of pioneer events, in his book, "Sixty Years in California," gives the date of the discovery 1840, and the discoverers a party of Sonorans traveling to Monterey. ... From this mass of contradictory data it is impossible to evolve the correct one. Nor is it probable that the exact date will ever be known. The strongest evidence seems to incline toward March 1842." Guinn further compares the two California gold discoverers, Lopez and Marshall: "Lopez, the real discoverer of gold in California, lived in obscurity, died in poverty and sleeps his last sleep in a nameless grave. Marshall, the reputed first discoverer, obtained celebrity — world-wide — in his latter years drew a pension of $3,000 a year from the State, and after his death the grateful republic erected a statue of bronze to his memory. Very little merit attaches to the discovery in either case; in both cases it was purely accidental; but whatever does, belongs to Lopez, not to Marshall." Isaac L. Given, an 82-year-old pioneer, wrote a letter to Guinn disputing the 1842 discovery date: "Dear Sir: I read in today's San Francisco Call a communication from your pen concerning the first discovery of gold in California in which you quote from the account on that subject written by Col. J.J. Warner, for whose accuracy in historical fact you vouch, and very properly, as I think. This account gives the date of the discovery of gold in June 1841. And you also quote Don Abel Stearns as giving the date of the discovery in March 1842. Now it is about the latter date that has influenced me to send you these lines. "I was one of the party, in which Roland and Workman were perhaps the best known members, who came from Santa Fe to California in 1841, arriving in Los Angeles in the fall of 1841. Shortly after our arrival, Dr. Lyman, a member of that party, and myself, were invited to dine with Don Abel, as all the natives called him, and while in his house he showed us a quart bottle of gold dust containing about 80 ounces obtained about where Colonel Warner describes the placers located. Now how could Mr. Stearns place that date a year later?" Pliny F. Temple, son-in-law of William Workman (who in 1842 established the Workman and Temple family homestead in what is now the city of Industry), wrote to his brother Abraham Temple on May 11, 1842: "There has been a gold mine discovered about forty miles from the Pueblo, the gold is of a fine quality & some grains have been found worth nearly three dollars. There are upwards of Fifty men to work washing the earth & there are expected the coming fall a large number of Sonorians to work in the mines. Should this prove to be as rich in quantity as it is in quality, the country will in a very short time have a different aspect." Francisco Garcia, Los Angeles Times, 1896 In a Los Angeles Times article of April 23, 1896, the 115-year-old Sonoran Ygnacio Francisco de la Cruz Garcia, aka Francisco Garcia, claimed to have been with Lopez at the gold discovery in 1838: "In the Santa Feleciana Cañon, some forty miles northwest of Los Angeles, he and Francisco Lopez and another man discovered the first placer gold found in the State, though this date does not coincide with that given by Don Abel Stearns and others. It would not be surprising, however, that there should be a lapse of three or four years in the memory of a man of his age." Leon Worden, in analyzing Garcia's claim, states: "The present story says Garcia claimed to have been with Francisco Lopez and another man when they made the first discovery of placer gold in California — in San Felicia (aka Feliciano, Feliciana) Canyon, i.e., the Piru area. According to Lopez' mining claim, however, which isn't specific to location, Lopez, Manuel Cota and Domingo Bermudez made the initial discovery. No doubt Garcia was around, though; Prudhomme (1922) says Lopez showed Garcia the location of his discoveries in Placerita and San Felicia canyons in 1843, and that Garcia returned to Mexico and came back with miners who worked the two areas." Charles J. Prudhomme, Historical Society of California, 1922 Charles J. Prudhomme, the historian for Ramona Parlor 109, Native Sons of the Golden West, discussed the gold discovery controversy in the "Annual Publication" of the Historical Society of Southern California in 1922: "This we will proceed to set forth in detail, and give ample proof to show that Marshall was not the first real discoverer of gold in California, nor was Sutter's Mill the place where the first discovery was made; but on the contrary, we earnestly allege that this discovery was first made by Don Francisco Lopez, and in southern California several years prior to the discovery by Mr. Marshall, that this was in 1842, and at the locality known as Placerito Canyon, and his second discovery was made the same year at a place known as San Feliciana, and not very far from the City of Los Angeles.

Prudhomme also brings up for the first time an account of the Lopez gold discovery by Francisca Lopez de Belderrain, a great-grandniece of Francisco López, who claimed to have been at a family reunion in 1914 when Catalina Lopez, niece of Francisco Lopez, recounted her personal memory of the first anniversary celebration of the Placerita gold discovery in 1843, when she was an 11-year-old child. Both the 1843 and 1914 gatherings presumably took place on the spot of the gold discovery in Placerita Canyon. In November 1920, Prudhomme rode out with Bilderrain and San Fernando resident Romona Lopez Shung (another relative of Francisco) to Newhall and Placerita Canyon. Prudhomme writes: "The circumstances of the discovery, as related by our guides, are these: Don Francisco Lopez, who was greatly trusted by the padres, had at this time charge of their cattle and stock in this section. And one day in the year 1842, when in company with another herdsman he sought some stray animals, they happened to ride into this Canyon, known as Placerito. These men, being weary, tethered their tired horses, and proceeded to make themselves comfortable, taking their siesta under the shade of the oak tree. After resting awhile, Don Francisco spied some bunches of wild onions growing nearby, and calling to mind that his aunt, at parting with him recently, had requested him to bring her home the first of these he could find, he began to pluck up some of these wild onions by the roots, and while thus engaged, to his astonishment he noticed attached to the roots of the onions, certain curious shining pebbles. So he then pulled out his hunting knife, and proceeded to dig more and more and still found attached to the bunches more and more of the same kind of shining stones. His curiosity being aroused, he filled his handkerchief with these shining stones, and having bunched up a lot of the onions for his aunt, mounted his horse and returned to his home. There he found his father, Don Juan Francisco Lopez, and requested him to take them to the Pueblo, and find out what they might be. Upon due research, they were found to be nuggets of gold. The news soon flew abroad, and many men flocked to this Canyon, and worked these placers in a primitive way." Prudhomme was then taken to a place in the canyon where Bilderrain, pointing to a certain spot, said: "This is the place of the discovery; this is the exact location." Prudhomme stated in conclusion: "Having in a measure gratified our desire to get first-hand data, and also original views of the identical spot where in the days of the missions Don Francisco Lopez made the first discovery of gold on the Pacific Coast, and having viewed this spot in company with his near relatives, who verify all our assertions in regard thereto, our mission being fulfilled to our satisfaction and joy, we turned our hustling auto about, and headed for the City of the Angels. Last, we add, let the truth of history prevail, and let justice be done, though the heavens fall. Let Mr. Marshall yield up the laurel of fame as the first pioneer discoverer of gold in California to the brow of Don Francisco Lopez, to whom it justly belongs." Rev. Zephyrin Engelhardt, O.F.M., Mission Historian

"The discovery, briefly, came about in this way, according to the Rev. Eugene Sugranes, C.M.F., who had the facts from the niece of the discoverer, Catalina Lopez. On March 9, 1842, the feast of St. Frances (Francesca) of Rome, Francisco Lopez, then in charge of San Francisquito Rancho determined to celebrate his birthday by adding to the dinner some fresh vegetables he had cultivated. From a bed of onions he pulled up a bunch of the plant. On shaking the soil from the roots, Lopez observed several yellow particles which on close examination proved to be genuine gold. In his excitement he forgot all about the dinner, and hastened to make known his happy find. Many fortune-hunters, especially from Sonora, crowded into the country, and the placer, as well as another discovered in the following year in the San Feliciano Cañon, on the same San Francisquito Ranch, but about eight miles to the west of Newhall, was worked more or less continuously till the year 1846." Arthur B. Perkins and Adolpho G. Rivera, 1930 The very first time we would see mention of a golden dream and a golden oak was in 1930 by historians Arthur B. Perkins and Adolfo G. Rivera.

Perkins and Rivera based their account on the testimony of Francisca Lopez de Belderrain. The two historians were preparing a celebration to commemorate the 88th anniversary of the Lopez gold discovery. On Feb. 23, 1930, they had Belderrain sign an affidavit attesting to the authenticity of her version of the story (among other small-town positions, Perkins was the local justice of the peace). Belderrain testified that Catalina Lopez had been shown the exact location of the gold discovery in 1843, and that in 1914, at a family reunion, Catalina had shown Belderrain and other family members the exact location of the discovery. The exact location was described as "the tree under which Francisco Lopez slept during the afternoon of March 9th, 1842 ... located on the property of Mr. Frank E. Walker, in Placeritos Canyon." Frank Walker signed an affidavit for Perkins on March 1, 1930, stating "that he has been shown the site of the first gold discovery of gold (sic) in California, by Mrs. Francisca Lopez de Belderrain and that said site is located in the W.½ of N.W.¼ of S.E.¼ of Section 5, Township 3 North, Range 15 West, S.B.M." Dedication of the Oak of the Golden Dream On March 9, 1930, Adolfo Rivera organized a dedication ceremony for the Oak of the Golden Dream as the purported location of the gold discovery by Francisco Lopez. Leon Worden writes: "It was Adolfo who determined which tree would be associated with the legend of Lopez's golden dream, on the word of relatives of a Lopez descendant who pointed it out to them 70 years after the fact."

The ceremony was to be hosted by Rivera's La Mesa Club along with Ramona Parlor No. 109 of the Native Sons of the Golden West (which Rivera also represented), along with the Kiwanis Club and Chamber of Commerce of Newhall-Saugus, the latter two organizations represented by Perkins. The program called for the unveiling of "a temporary tablet, over a mound of granite boulders unearthed in Placeritos canyon by Mr. F.E. Walker, after being covered by brush and debris for 75 years, marking the spot where gold was first discovered in California, on March 9th. 1842, by Francisco Lopez, a native Californian." Rivera officiated as master of ceremonies. Speeches were made by, among others, Belderrain, State Sen. Reginaldo F. del Valle (grandson of Antonio), Perkins and Walker. After the speeches, the program for the ceremony stated, "You will be shown the 500 year old oak tree, under whose shade Francisco Lopez enjoyed his mid-day siesta on the day of his discovery." Rivera said in his speech that day: "This date marks the 88th anniversary of the discovery of gold, on this very spot, in 1842. That the world may know, that the Northern historians may learn; that our State authorities may take notice and insert these facts in our school text books, we are placing a temporary tablet over a mound of boulders placed here 3/4 of a century or more ago and but lately unearthed by Mr. Walker, the owner of these premises. La Mesa Club, with a membership of Native and Adopted Sons of California, will place a tablet on yonder oak, ‘neath whose shade, the discoverer slept his siesta on that eventful day." He further proclaimed: "We of this Southland do now inform the historians of the North and announce to the world that we proclaim our right to be recognized in the history-making epochs of our state, that this discovery must be presented in the textbooks in our schools, and we advise legitimate writers on California history to take heed, or they will be branded as falsifiers and concealers of the truth." Perkins stated in his speech: "(W)e wish to recall March 9, 1842, when Francisco Lopez arose from under that Tree of the Golden Dreams, and made that epochal Discovery of Gold." Thus it appears that in 1930, the concept of the Oak of the Golden Dream was first introduced. There were two plaques placed at the Oak of the Golden dream that day. One plaque affixed to the tree itself bore the inscription: ENCINO DE LOS ENSUENOS DORADOS DE FRANCISCO LOPEZ. OAK OF THE GOLDEN DREAMS. PLACED BY LA MESA CLUB. MARCH 9TH 1930. The other plaque affixed to a pile of boulders next to the tree stated: FRANCISCO LOPEZ HERE DISCOVERED THE FIRST GOLD IN CALIFORNIA. MARCH 9, 1842. THIS PLATE PLACED MARCH 9, 1930 BY THE RAMONA PARLOR No 109, N.S.G.W., LA MESA CLUB, KIWANIS CLUB OF NEWHALL-SAUGUS. By 1957, both plaques had been stolen. The tree plaque was never seen again, although the boulder plaque was said to have been recovered. In Conclusion... So ... was the story of the Oak of the Golden Dream fact or legend? One thing we can say for certain is that Francisco Lopez made the first documented gold discovery in California history in the Santa Clarita Valley, most likely in Placerita Canyon. There are obviously differing opinions as to the exact location of the gold discovery, the exact date, and the exact circumstances under which Lopez discovered the gold. With the evidence that's available to us today, as presented in this article, we may never know for sure what really happened. The truth may have died with Francisco Lopez.

Alan Pollack, M.D., is president of the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society.

|

Dissecting the Dream: Fact, Fiction & the Golden Oak, by Alan Pollack

New York Observer 10-1-1842

U.S. Treasury Voucher 1843

Abel Stearns Letter 1867

Francisco Lopez

Pedro Lopez (Brother)

Maria Felis (Wife)

Maria Concepcion (Daughter)

Francisco Ramon (Son)

Catalina (Pedro's Daughter)

Francisco "Chico" Lopez Obituary 1900

As Told by Jose Jesus Lopez

Sutter's Fort Error 1905

Prudhomme 1922

Engelhardt 1927

Francisca Lopez de Belderrain

Belderrain Story 1930

Who's Who, by Belderrain

• Story: Sutter, Marshall Knew They Weren't First

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.