|

|

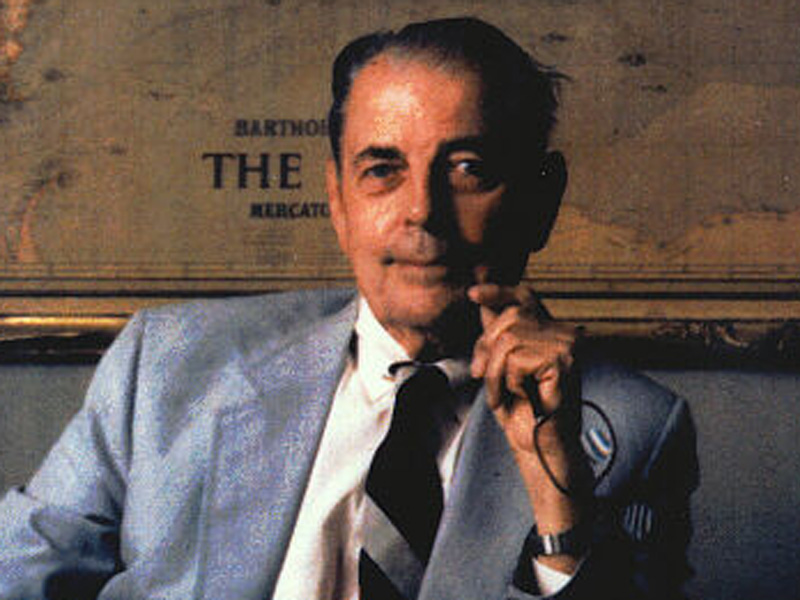

Scott Newhall, San Francisco Chronicle, 1968

San Francisco, California

Click image to enlarge

Scott Newhall in his office at the San Francisco Chronicle, 1968. Note the model of the side-wheel tug boat on the wall when you click to enlarge. When Scott Newhall became executive editor of the San Francisco Chronicle in 1952, its circulation was half that of William Randolph Hearst's Examiner. Scott was determined to eclipse the Examiner in subscriptions — and when he did, it was champagne on ice for the entire staff. A teetotaler himself, Scott stuck to ginger ale.

Scott was born Jan. 21, 1914, in San Francisco and joined the staff of the Chronicle in 1934 as a summer replacement photographer. A year earlier, during his sophomore year at UC Berkeley, he eloped with the woman who would become his lifelong companion, Ruth Waldo. The couple enjoyed sailing and antique hunting. It was during a hunt in Mexico for a lost Aztec gold mine that Scott got mad at his horse and kicked it. It kicked back and Scott ended up losing his right leg. Scott and Ruth never did find the mine, but they did go on to have four children: Skip in 1938, followed by twins Tony and Jon in 1941, then daughter Penelope (Penny) in 1943. Penny died in a runaway truck accident in 1955. By the early 1960s, still the hired head of someone else's Chronicle, Scott set out to buy a newspaper of his own. In 1963 the Santa Clarita Valley's weekly newspaper, The Newhall Signal and Saugus Enterprise — named both for his great-grandfather Henry and for Henry's Massachusetts birthplace — came on the market. Scott and Ruth purchased it, commuting to Newhall to run it. It was "game on" as Scott introduced Santa Clarita Valley readers to his inimitable editorial style along with his motto, "Vigilance Forever," which made its first appearance Jan. 9, 1964. Scott was familiar with the area as a shareholder in the family business, The Newhall Land and Farming Co., which at one time owned 46,460 acres of the Santa Clarita Valley and now was preparing to build an entire "new town" called Valencia. Tired of living out of suitcases, Scott and Ruth rented, then purchased the Warring mansion in Piru in 1968. All the while, Scott was still running the show at the Chronicle. He had one more thing to do before he left the Bay Area for good: In 1971 he ran for mayor of San Francisco. It didn't work out too well. Scott captured just 3.44 percent of the vote, finishing fifth behind incumbent Joseph Alioto and third-place challenger Dianne Feinstein. After that, Piru and the Santa Clarita Valley became the Newhalls' permanent home. Scott ramped up his editorial fervor, calling for the head of a bureaucrat or politician one day and threatening to drop king-sized diapers by helicopter the next, because those darned cows shouldn't be roaming the hills naked in view of freeway motorists. The Santa Clarita Valley of the 1960s and '70s was known casually as the "Newhall-Saugus area" or the "Newhall-Saugus-Valencia-Canyon Country area." Believing the valley needed a solid, memorable name, Scott instructed reporters to refer to the area as "Valencia Valley" in news stories, but it didn't catch on with readers — especially those in Canyon Country who weren't necessarily enamored with Newhall Land or its new town. Scott and Ruth traded off the top staff positions at the paper over the years and engaged sons Jon and Tony to share in the editorial and publishing responsibilities. Despite competition from the Los Angeles Times and Daily News, aka the Valley News & Green Sheet, the Newhalls turned a small, local weekly paper into a twice-weekly in 1965, then thrice-weekly in 1966 as they marched toward eventual daily publication. The Newhalls' community participation wasn't limited to newsprint. In 1972, Newhall family members organized the first Santa Clarita Valley Boys & Girls Club Auction. It was Ruth who came up with the idea of forming the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society in 1975; a decade later, it was Ruth who convinced other community leaders that the time was right to form a city. By that time, Scott and Ruth had set the wheels in motion to relinquish control of The Signal. Back in 1972 they brought in an investor in the person of Charles Morris, a young newspaper publisher in the South, and used his money to pay off the bank loan they had used in 1963 to buy the paper. The new money gave Morris an option to buy The Signal after six years. When 1978 came, Scott and Ruth wanted to buy him out, but Morris chose instead to exercise his option. In terms of circulation, The Signal was Morris' largest property in California. Morris would end up owning the paper longer than anyone — 37 years. Scott and Ruth asked to stay on as editors in 1978 and signed a 10-year noncompetition agreement. In 1986 they shepherded The Signal through its move from 6th Street in Newhall to "Auto Row" in Valencia to be in close proximity to their major advertisers, who had made the same move a decade earlier. In 1988 when the 10-year mark arrived, Scott and Ruth left the building — and opened their own shop right down the street on Valencia Boulevard, intent on beating The Signal in circulation as Scott had done decades earlier to Hearst. This time the outcome would be different. Eight months and $1.3 million later, their thrice-weekly Citizen newspaper folded and Scott rode off into the sunset. In 1992, acute pancreatitis landed Scott at Henry Mayo Newhall Memorial Hospital in Valencia, where he died Oct. 26 of that year. He was 78. For a quarter-century, from 1963 to 1988 at The Signal and beyond with The Citizen, Scott and Ruth Newhall recorded, influenced and molded the goings-on in the Santa Clarita Valley as the area grew from a sleepy L.A. backwater into a vibrant, self-sustaining family community. TN1968: 9600 dpi jpeg from original photograph | Online image only |

SEE ALSO:

Oral History 1988/89

Family Photos x7

World Cruise 1936

Scott, Skip, Tony, Jon 1944

Chronicle x3

Buys Signal 1963

12/23/1965

Anguilla 1967

Scott in England 1969

Eppleton Hall 1970

Pinback: Scott for Mayor 1971

Scott for Mayor 1971

Tony Newhall & Clarion Publisher Jackie Storinsky 1971

Signal Ingot ~1973

Signal 1980s

Silver Spur 1991

Signal Special Edition Upon Scott's Death 1992

Historical Society 2/1993

Video: Ruth Interview 2000

• Ruth Obituary 1

Ruth Tribute 1/2004

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.