|

|

|

Images courtesy of Eastern California Museum Anonymous photo album donated 2018 by Robert Jones to the Eastern California Museum in Independence, Calif. Original captions:

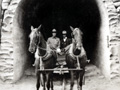

Views of Construction on Los Angeles Aqueduct. 1. One of the finished Tunnels in the Saugus Div. 2. Building the Core Wall of the Fairmont Dam. 3. Steam shovel excavating deeps cuts in the Antelope Division. 4. Aqueduct in the Red Rock Country lined & ready for Cover. 5. Putting the Concrete Cover on the Aqueduct in the Mojave Division. (No number) Building the Aqueduct through the Mojave Desert. 6. A Section of finished Conduit. 7. Aqueduct Construction Camp in the Jawbone Division. 8. Tunnel Adit in the Boulder Peak Section. 9. The Trail to Tunnel 12 in the Boulder Peak Section. 10. Building the Conduit on steep Hillside in the Grapevine Division. 11. Putting the Cover on the Side Hill Work in the Grapevine Division. 12. Concrete Flume in Water Canyon, Jawbone Division. 13. Aerial Tramway for lifting the men & materials to the side Hill work in Sand Canyon, Grapevine Division. 14. Construction Camp in Sand Canyon. 15. Caterpillar Traction Engine hauling Rock for Concrete. 16. Two of the finished Tunnels in the Saugus Division. 17. A finished Tunnel in the Jawbone Division. 18. South Portal of the Elizabeth Tunnel. This Tunnel is 5¼ Miles long. 3 Miles of it have already been driven. 19. Prize Tunnel Crew, Los Angeles Aqueduct. This Crew made a footage of 1,061 feet at the North End of Tunnel 17 M. during the Month of August, 1909, which is the World's Record in Tunnel driving. 20. Dove Springs Camp on the Red Rock Spur. Railroad built by the City. 21. Dredge No. 1 in Owens Valley Division. 22. Dredge No. 1 Undercutting Bank of main Canal with Water Jet. 23. Municipal Cement Plant at Monolith. Built by City of Los Angeles in Connection with the Aqueduct.

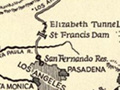

About the Los Angeles Aqueduct. In the early days of the pueblo of Los Angeles, the city water supply was obtained from the Los Angeles River. Water was brought to the pueblo from the river by way of a series of ditches called zanjas. The main ditch was called the Zanja Madre (mother ditch). By 1868, the population of the pueblo had grown to between 5,000 and 6,000 people. At that time, the city entered into a contract with a private water company, the Los Angeles City Water Company, to lease the city's waterworks for a 30 year period to provide water to the city. In 1875, Fred Eaton became superintendent of the water company. He hired Irish immigrant William Mulholland in 1878 as a zanjero (ditch tender). Although he had no formal schooling, Mulholland proved to be a brilliant employee, who taught himself engineering and geology. Mulholland became friends with Eaton and quickly moved up the ranks of the Water Company, becoming Superintendent in 1886. By the turn of the century, the population of Los Angeles had grown to more than 100,000 people. It was becoming obvious that the Los Angeles River would not have enough water to supply this growing city in the future. Eaton had traveled to the Owens Valley, east of the Sierra Nevada Range, in the early 1890's and came up with a gradiose idea of diverting water from the Owens River to the increasingly thirsty city of Los Angeles 233 miles away. In 1902, the City of Los Angeles took over the city's water supply and the Bureau of Water Works and Supply was formed with Mulholland continuing as Superintendent. Eaton convinced Mulholland to travel with him to see the Owens Valley, which they did by buckboard, passing through the Newhall-Saugus area in 1904. Mulholland was convinced by Eaton during this trip in 1904, and hatched an idea to build an aqueduct between the Owens Valley and Los Angeles. But to accomplish this would first require buying up land and water rights in the Owens Valley. The residents of the Owens Valley, however, had other ideas. They were looking forward to a reclamation project sponsored by the federal Bureau of Reclamation. Eaton, with the help of his friend and local chief of the Reclamation Service J.B. Lippincott, began buying up land in the Owens Valley under the pretense that the land would be used for the reclamation project. By July 1905, Eaton had bought up enough land to secure the land and water rights to build the aqueduct. The Los Angeles Daily Times headline of July 29, 1905 would proclaim "TITANIC PROJECT TO GIVE CITY A RIVER. Thiry Thousand Inches of Water to be Brought to Los Angeles. Options Secured on Fourty Miles of River Frontage in Inyo County...Stupendous Deal Closed." Bond issues were passed by the voters in Los Angeles in 1905 to finance the purchases made by Eaton and in 1907 to finance the construction of the aqueduct. Mulholland began construction of the aqueduct in 1908. It would prove to be an engineering marvel extending 233 miles from the Owens Valley to Los Angeles with the water traveling the distance purely by gravity without the need for pumping systems. The project also featured the 5 mile long Lake Elizabeth tunnel. The aqueduct would pass through San Francisquito, Bouquet, and Soledad canyons on its way to the terminus in the San Fernando Valley. Mulholland miraculously completed the project on time and in budget by 1913. He became an absolute hero to the City of Los Angeles (but reviled by the people of the Owens Valley for decades to come). The aqueduct was completed with it's terminus at the southern end of the Newhall Pass with a cascade of water flowing down the mountainside in what would become present day Sylmar. The original cascade of water can still be seen when traveling on Interstate 5 through Sylmar in the San Fernando Valley. On November 5, 1913, over 40,000 Los Angeles residents came to the San Fernando Valley to see the first water from the Owens Valley complete the journey to Los Angeles. The city's hero Mulholland presided over the ceremony and instructed the water gate to be opened with the famous words "there it is, take it." The November 6, 1913 issue of the Los Angeles Times proclaimed: "GLORIOUS MOUNTAIN RIVER NOW FLOWS TO LOS ANGELES." As part of the Aqueduct opening ceremonies, Exposition Park in Los Angeles was dedicated the next day on November 6. Alas, Mulholland was to experience the proverbial "rise and fall" story. His hero status would forever be tarnished by the St. Francis Dam Disaster which occurred 15 years later in March, 1928. But on a fine November day in 1913, Mulholland was truly on top of the world. — Alan Pollack

About the Eastern California Museum. The Eastern California Museum was founded in 1928 and has been operated by the County of Inyo since 1968. The mission of the Museum is to collect, preserve, and interpret objects and information related to the cultural and natural history of Inyo County and the Eastern Sierra, from Death Valley to Mono Lake. The Museum collection is held in public trust, and a computerized database with over 15,550 records is used to manage the Museum's extensive collections. In addition to those artifacts, the Museum also houses about 27,000 historic photographs of the Eastern Sierra region, the majority of which date from the late 1800s through the 1950s. The Museum is also an outstanding resource for researchers, and typically handles about 200 requests for information or photo reprints per year. Artifacts and information are interpreted for the public through the Museum's permanent exhibits and an annual rotating, special exhibit from the collection. The Museum also maintains archives that make up the History Files, and the Family Files, both of which contain newspaper clippings, original documents, and other information about the towns, people, and subjects that have played a role in the history of Inyo County and the Eastern Sierra. The Frank M. Parcher Research Library is another excellent source of information for researchers and the general public. The Museum also presents educational programs, special events, and lectures and talks that are free and open to the public. In addition to the main Museum buildings at the Museum's Independence campus, the Eastern California Museum also maintains the historic Commander's House and Edwards House in Independence, and the Mary DeDecker Native Plant Garden on the Museum grounds. The Eastern Californian Museum, located at 155 N. Grant St. in Independence, is open daily and weekends (except major holidays) and admission is free, although donations are appreciated.

EC1801: Download individual images here.

|

More Photos:

Archive Footage

Complete Report on Construction 1916

Book: The Water Seekers (Nadeau 1950)

Route Map 1908

Workers Angered by Pay Cut, Spoiled Food 1909

Saugus Division Tunnel 1909

Photo Album: Construction 1908-1913

Construction 1910

Power House 1, ~1910

Elizabeth Tunnel 1910

Whitney Siphon 1910

Saugus HQ 1907-12 x3

Water Canyon Postcard 1911

Letter of Recommendation 1912

Jawbone Siphon ~1912

Cement Plant, Newhall ~1912

Jawbone Siphon 1913

Canyon Country ~1913

Newhall ~1913

Deadman Canyon Siphon, Saugus x2

Cascades 1914

Cascades 1915

Power House 1

Construction 1915

Terminus 1918

Placerita x3

Annual Report 1923

Map & Facts, Bullock's 1926

Annual Report 1929

LADWP Propaganda

1926 (Rev. 1932)

Bouquet Dam 1933-34

Saugus Nuclear Plant 1960

Jawbone Siphon 1960s

Jawbone Siphon 2016 (26)

LADWP House at Dry Canyon Reservoir 2020

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.