La Puerta: Gateway to the Santa Clarita Valley.

|

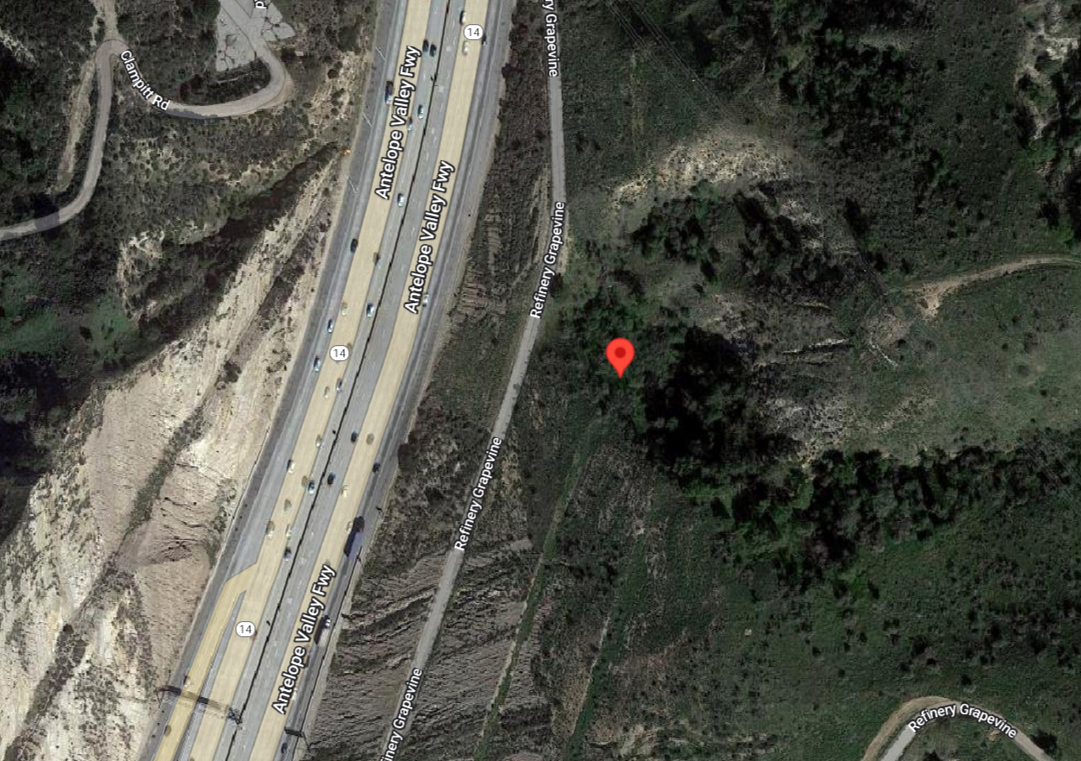

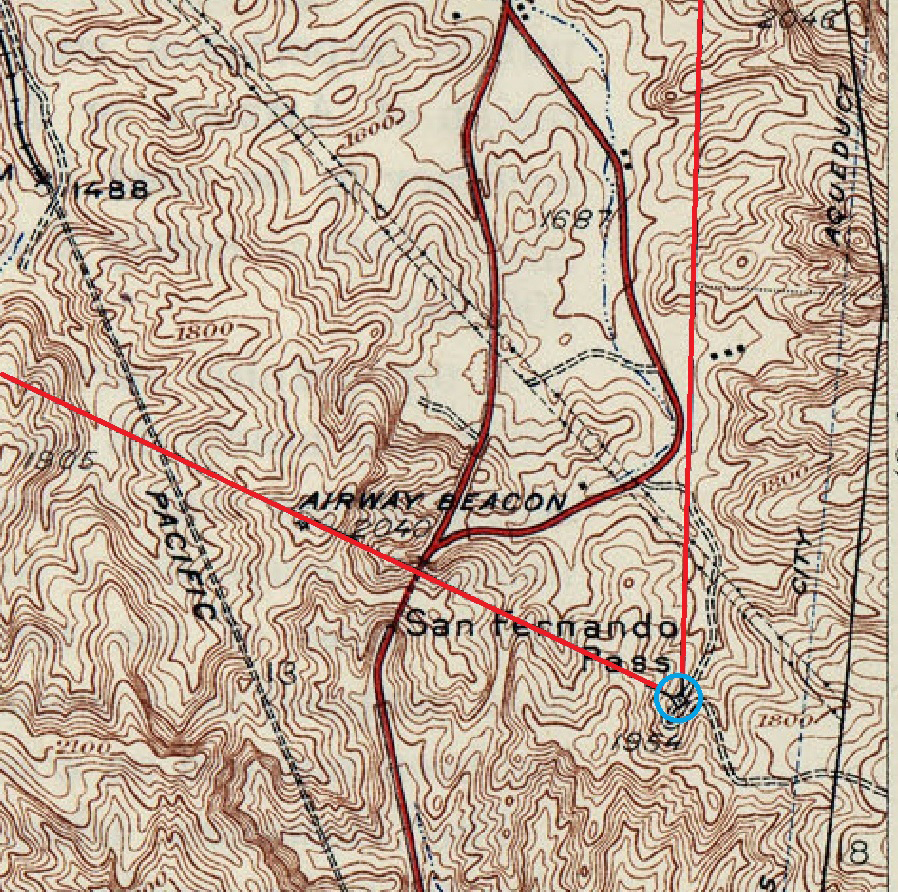

When Gaspar de Portolá and his expeditionary force entered the Santa Clarita Valley from the south in August 1769 and encountered the inhabitants of Tochonanga in the vicinity of today's Eternal Valley Cemetery, they traversed the mountains by way of an ancient road that their Native hosts had marked out for them[1] — a road that had served local travelers since time immemorial. This was Camino Viejo, the "old road" through the area we know as the Newhall Pass. In the coming decades, as the Spanish colonists at the Mission San Fernando established ranchos in the San Fernando and Santa Clarita valleys, they laid a sapling or two across a narrow switchback in the road to bar it,[2] in order to stop the cattle of one ranch from wandering onto the other. This was La Puerta, "the door." La Puerta would remain an important point on the map up to and beyond the time of Henry Mayo Newhall. In a way, it is still a southern entry to our valley. It sits atop the eastern slope of the 14 Freeway.

Metes and Bounds.

We must pause our narrative long enough to give credit where it's due. In late 20th Century, local historians misinterpreted the location of La Puerta, conflating it with a fork in the creek just over a mile deep into Elsmere Canyon. A young Jerry Reynolds in 1975 more or less correctly placed the entry point "a few hundred feet to the northeast" of Beale's Cut[3], and in 1992 he came across an old surveyor's map showing the location.[4] It was an opportune find. The community was fighting to stop a landfill from coming into Elsmere Canyon, and here was a historic site worthy of veneration.[5] However, when an application was drawn up in 1993 seeking state historic landmark status for "La Puerta Del Camino Viejo," Reynolds described the old door's location as "a curious spine of sandstone and weathered rock [that] extended across the canyon,"[6] and the application placed it near a picturesque waterfall at some very wrong coordinates.[7] Neither the historic designation nor the landfill came to fruition. We are indebted to Stan Walker, a consummate researcher who hunts down ancient land office records and scours archaic court case files, for setting us straight. (This is written in 2023.) When Mexican Army Lt. Antonio del Valle received the Rancho San Francisco — the ex-mission rancho in the Santa Clarita Valley — as a gift from California's governor in 1839, La Puerta demarcated the southeastern tip of his property in the legal description:

... on the South by a line drawn from said tree to the East through the hills until it reaches the door (La Puerta) or bar which is in the high road from San Fernando to San Francisco at the very foot of the cuesta of San Fernando where the road is very narrow and where it was formerly completely fenced by bars tied to an Oak Tree (Encino), the mountains coursing down on either side and leaving a very narrow pass...

Shortly after Del Valle's death in 1841 (and likely before), at least two crude maps, or diseños, were created to show the extent of his property. Only in the vaguest sense do they correspond with anything one would recognize as a map of our valley today. Becker writes: "The responsibility for drawing up the necessary petition, and the diseño, was that of the man who wanted the land. Mexican California was not awash with literacy nor with cartographic skill. [Diseño maps] have been regarded as quaint, primitive, fanciful. Indeed they are. [But] in Mexican California they satisfied one of the requirements in the process of obtaining government land."[8] Things changed a few short years later with California statehood. The old diseños weren't good enough for the United States government, nor were many of the old legal descriptions that called for a boundary line to be drawn from "this tree over here" to "that rock over there." But La Puerta survived as the southeastern terminus of the Rancho San Francisco under American rule — and even a tree that stood alongside La Puerta with "S.F.5" carved into it would eventually worm its way into the legal description.

Title Search.

Antonio del Valle's heirs petitioned the U.S. government for confirmation of title to the Rancho San Francisco in 1852.[9] Deputy U.S. Surveyor Henry Hancock, a Harvard-educated lawyer, conducted the official survey. By the time the land was finally confirmed to the Del Valle family two decades later, when they no longer owned it, new maps published in 1870 and 1874 depicted the rancho in its ultimate configuration. The maps show the old road (Camino Viejo) and the "S.F.5" oak tree, as well as a new road, running through the southeast corner of the property. The 1850s and early 1860s were a turbulent time financially for the Del Valles. Antonio's sons Ygnacio and José del Valle, along with co-owner William Wolfskill, sold the rancho to Thomas Bard on behalf of the Philadelphia & California Petroleum Company in 1865.[10] The legal descriptions in several deeds from 1865 and 1868 mirror the 1839 original.[11] In 1873, when the rancho was purchased by Charles Fernald and J.T. Richards of Santa Barbara, the legal description was shortened but retained the reference to La Puerta:[12]

...East two hundred and fifty six chains to an oak tree marked "S.F.5," being the point called La Puerta, at the foot of San Fernando Pass.

Why Beale's Cut?

When General Frémont sent his troops south through our valley on their march to San Fernando in January 1847, they "mounted the precipitous Indian trail," as Perkins termed it[13] — Camino Viejo. Why, then, did early American settlers abandoned the good, old Camino Viejo that had served travelers for hundreds and perhaps thousands of years, in favor of a new road just 1,240 feet due west of it, over a mountain that would have to be cut away to make it passable? Stagecoaches. There was no way for them to maneuver through a steep switchback that was narrow enough to be blocked off with a log. By the time newspaper publisher Horace Bell famously described Phineas Banning's harrowing ride in a big Concord coach in December 1854,[14] the highway contractor Gabriel Allen had already "put the first cut through the summit."[15] Ripley writes: "[T]his new road had been put up a canyon to the west of the Cuesta Vieja" — Old Hill, as this section of the Camino Viejo was known — because the grade was lower there.[16] In 1857, it still took "four yokes of cattle and a windlass" to get a certain teamster's wagons over the new pass.[17] Banning had a similar experience on another run in May 1858 in the company of a newspaper reporter. Despite proceeding over the summit "somewhat more carefully than Banning's usual custom," the correspondent writes, it still took three men to ease the carriage down the cliff after locking the wheels and sending the horses down separately.[18] Such a sorry state of affairs was not going to work for John Butterfield's Overland Mail Company. Company officials arrived in Los Angeles in June 1858 to determine their wagon route and plan station locations. The Los Angeles Star reported: "It is the desire ... of the company that the stages should pass through our city, provided the only obstacle to that arrangement, and a very serious one it is, be removed — namely the present condition of the San Fernando Hill [the new pass] and San Francisco Pass [San Francisquito Canyon]."[19] The Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors took immediate action. It ordered an engineering survey, formed a citizens committee, and offered up to $3,000 for road repairs, provided enough "citizens of this section of the state" would loan the money to the county treasury interest-free. The lenders were identified as "Banning, Stearns, Griffin, Bachman & Co., Mellus, O.W. Childs, Andrés Pico, and Del Valle."[20] The contract went to Gabriel Allen. The Los Angeles Star reported: "Mr. Allen submitted three propositions, two of which were for repairs of a more extensive character than the Board contemplated, but the committee could only accept that which was within the amount of funds at their command." The corresponded added: "We lately passed over this road and were surprised to find so monstrous an evil existing on the great leading thoroughfare of the southern country."[21] Over the next six years, Allen's more extensive vision for the road would come to fruition as the Board of Supervisors let contract after contract for road improvements. In 1861 it awarded the job to the ex-Mexican General Andrés Pico, and in 1863 to his onetime battlefield adversary, Edward F. Beale. Eliminating the monstrous evil meant lowering the grade of the road by cutting through the mountain — deeper and deeper, a bit at a time. Completed by Beale's hired hands to its ultimate 90-foot depth in 1864, Beale's Cut would serve teamsters and early motorists for the next 46 years until it, too, was abandoned for an even newer route that included a tunnel through the mountain. It is another route we use today — Sierra Highway — sans tunnel, which was blasted into history in 1938.

1. From Crespí's journal: "About half past six in the morning we left the place [San Fernando] and traveled through the same valley, approaching the mountains. Following their course about half a league, we ascended by a sharp ridge to a high pass, the ascent and descent of which was painful, the descent being made on foot because of the steepness. Once down we entered a small valley in which there was a village of heathen who had already sent messengers to us at the valley of Santa Catalina de Bononia [San Fernando Valley] to guide us and show us the best road and pass through the mountains." See also Costansó. 2. Perkins, The Signal, March 19, 1964. 3. The Signal, September 29, 1975. 4. The Signal, November 15, 1992. 5. See for example The Signal, May 26, 1993. 6. Quote from State Historic Landmark application, cited by Stan Walker. 7. The incorrect coordinates were N34.353312, W118.49047. 8. Becker, Robert H., "Designs on the Land: Diseños of California Ranchos and their Makers." San Francisco: The Book Club of California, 1969. Preface and Introduction (unnumbered pages). 9. Perkins: https://scvhistory.com/scvhistory/perkins-rsf-1957.htm. 10. A competent account of the period can be found here: https://scvhistory.com/scvhistory/robinson_storyofvalencia_1967.htm. 11. Records of deeds, Los Angeles County Registrar-Recorder: William Wolfskill to Ygnacio del Valle, Deeds, Book 7 pg. 104 (3/18/1865); Jose Ygnacio del Valle to Thomas Bard, Deeds, Book 7 pg. 106 (3/18/1865); Thomas R. Bard to Robert H. Gratz, Deeds, Book 7 pg. 180 (3/29/1865); Robert H. Gratz to the Philadelphia and California Petroleum Co., Deeds, Book 13 pg. 47 (9/16/1868). Research by Stan Walker. From the 1865 and 1868 deeds: "...on the South by a line drawn down said tree to the East through the hills until it reaches the door (la Puerta) or bar which is in the high road from San Francisco to San Fernando at the very foot of the Cuesta of San Fernando where the road is very narrow and where it was formerly completely fenced by bars tied to an oak tree the mountains coming down on either side and leaving a very narrow pass." 12. Ibid. 13. Perkins, The Signal, October 24, 1946. 14. Bell, Horace, "Reminiscences of Ranger" (1881). Advertisers Composition Company version (1967), Vol. 3, pp. 323-324. 15. Ripley, Vernette Snyder, "The San Fernando Pass," Part 10: The Butterfield Overland Mail. In The Quarterly, Historical Society of Southern California, March 1948. 16. Ripley, ibid., Part 8: The New San Fernando Pass, 1854. 17. Reminiscences of J. Kuhrts, published in the Historical Society of Southern California Annual Publication of 1906. More: https://scvhistory.com/scvhistory/hs9029.htm. 18. Daily Alta California, May 29, 1858. 19. Los Angeles Star, June 12, 1858. 20. Ibid. 21. Los Angeles Star, July 3, 1858.

|