|

|

Rancho San Francisco:

A Study of a California Land Grant

By Arthur B. Perkins

The Historical Society of Southern California Quarterly | June 1957

|

Webmaster's note. In this major work, SCV Historian A.B. Perkins (1891-1977) traces the history of the Rancho San Francisco, which once encompassed more than 100,000 acres of the Santa Clarita Valley, from its Spanish origins to its development as a 20th-century township. Along the way, Perkins takes the reader on a trip through the many political changes that affected the valley, and he delves into the discoveries of gold and oil on and adjacent to the rancho, which were what all the fuss was about. His attention to the partitioning of Camulos, which managed to maintain its pastoral life even as the rest of the rancho experienced the travails of progress, serves a dual role as history and subtext. It is 2014 as we add this work to the archive, and it is interesting to note that certain details in the text have been overlooked, or at least they haven't been highlighted in quite the same manner, over the last few decades. Perkins was a thorough researcher and, at various times, a judge and a real estate developer; he was well versed in the texts at the Bancroft and other major libraries, and he had access to court and property records — all of which he drew upon, as appropriate, for this story. In extremely rare instances where no written record was available, he relied upon the memories of "old timers" he had known; as much as we might like to re-question Sarah Gifford and Addi Lyon about their version of events when they deviate from the modern record, we can't. Perkins submitted this text for publication in the Historical Society of Southern California's Quarterly, and he filed his original manuscript with the Newhall Library. To the extent there are variations, usually typographical, between the two texts, the published version has been favored here. The placement of footnotes 26, 41 and 52 is absent from both versions. Also, rather than add a second layer of footnotes on top of Perkins' original footnotes, which appear here, we've sparingly interjected a few notations inline. Perkins included three photographs with the published version: two photographs of plaques placed in 1930 at the dedication of the Oak of the Golden Dream (an event at which Perkins represented the Kiwanis Club); and a photo of the "old milk house" below the estancia at Castaic Junction. All other photos have been added for this online version.

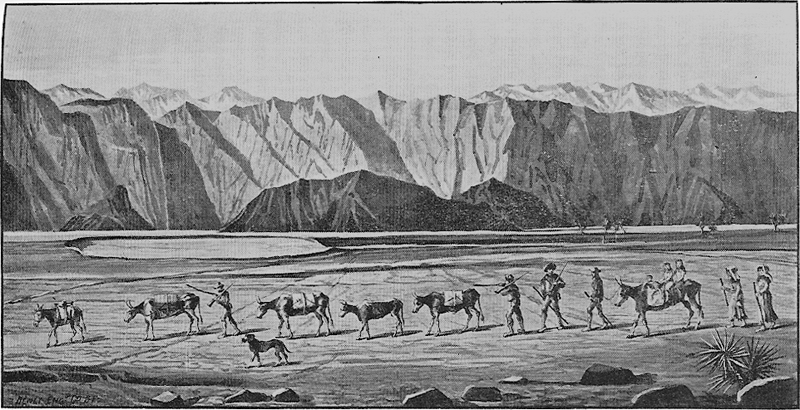

New England prestige dating commences with the landing of the Mayflower Pilgrims. Correspondingly, California history commences with the Sacred Expedition, sent by Fr. Junipero Serra from San Diego in 1769, to find the legendary Bay of Monterey. Don Gaspar de Portola was the military leader, Frs. Juan Crespi and Gomez were spiritual leaders, and Don Miguel Costanso was the engineer of the expedition. Each kept diaries. The Sacred Expedition becomes the first visitation of white men to the aboriginal population of the area yet to become Rancho San Francisco. The diaries tell of encampment in the vicinity of today's Tunnel Station, August 7, 1769. The morning of the eighth, the party painfully climbed and descended rugged and precipitous mountains into the headwater area of the Santa Clara River.[1] Fr. Crespi's description of the country through which the expedition marched down the Santa Clara River bed to today's Castaic Junction, cannot be bettered: The country, from the village to the watering place, is delightful and beautiful in the plain although the mountains that surround it are barren and rough. In the plain, we saw many tall and thick cottonwoods and oaks. The watering place consists of an arroyo with a great deal of water which runs in a moderately wide valley well grown with cottonwoods. We stopped on the bank of the arroyo where we found a populous village in which the people lived without any cover, for they had no more than a light shelter fenced in like a corral. The Soldiers called it Rancheria del Corral, and I called it Santa Rosa de Viterbo. As soon as we arrived, they gave us many baskets of different kinds of seeds, and a sort of sweet preserve like little raisins, and another resembling honeycombs, very sweet and purging and made of the drew that sticks to the reed grass. It is a very suitable site for a Mission, with much good land, many palisades, two very large arroyos of water and five large villages close together.[2] The reader has thus progressed from Newhall Pass to Castaic Junction. The corrales, or villages, vanished 75 years ago. The last in use was about three miles westerly from Castaic as in 1887. The two streams, the Santa Clara River and Castaic Creek, still run. The populous village was known as "Chaguayabit," or "Kash Tuk," and not far from today's Castaic Junction. (Ed. Note: Perkins' typewritten manuscript says Chaguayabit "of" Kash Tuk, which conveys a different meaning.)

The expedition remained encamped August 9th, continuing down the Santa Clara river bank the 10th and 11th. That night they camped by the populous Indian village of Kamulus, close to today's Piru, and in the afternoon of the 12th passed over the limits-to-be of Rancho San Francisco and into the wider reaches of the Santa Clara valley.[3] The expedition set-up was admirable. Fr. Crespi's diary described the trip with an eye to establishment of future missions, blanketing existing Indian villages, their population, water availability and factors of economic support. On the return in December, the expedition made use of the pass by Calabasas. When the reports of the Sacred Expedition were studied in Mexico City, His Excellency, the Viceroy, Marquis de Croix, at once wrote, charging Fr. Serra with the establishment of five more Missions, one of which was to be known as Santa Clara.[4] Missions, however, necessitated soldiers to act as guards, supplies, and some monies, none of which were then forthcoming. In 1773, the founding of Santa Clara Mission at the site of Chaguayabit, the Rancheria del Corral, is again written about but nothing done.[5] In 1776, Fr. Francisco Garces entered the valley by the route of the Sacred Expedition, came down the river bed but passed to the north of Chaguayabit on his expedition to Tulare Lake.[6] This was the first recorded visit of a white man since 1769. The Mission Fathers were still using the pass by Calabasas. Fr. Garces stayed ten days at one of the Indian villages and, in his turn, was impressed by the hospitality and affability of the local Indians. Fr. Serra dies in 1784. He was succeeded by Fr. Fermin Lasuen as Presidente of the California Missions, who undertook the task of filling the gaps in the Mission chain. Between San Gabriel and San Buenaventura Missions was over seventy-five miles, a tough three-day march. Also, the intervening Encino (San Fernando) Valley was the site of a very large number of Indian rancherias, or villages, too isolated from existing Missions for conversions, or administration.

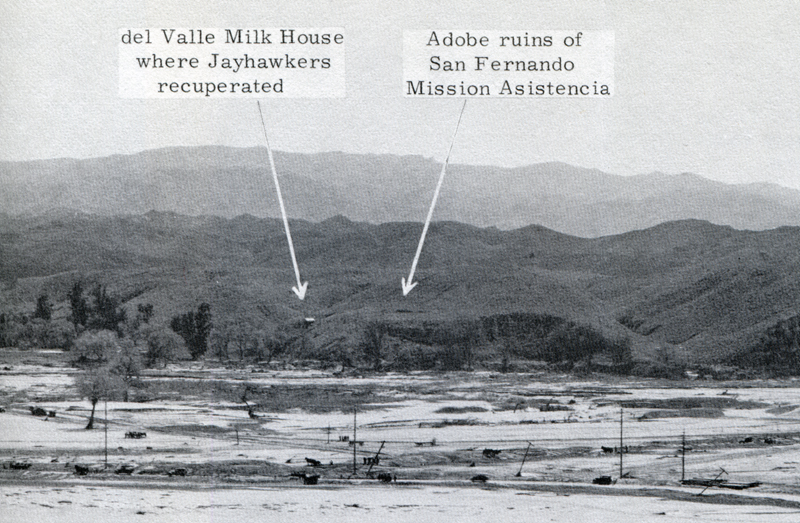

In 1795, therefore, Fr. Lasuen ordered Fr. Vicente de Santa Maria to examine and report on possible Mission sites. Triunfo, Chaguayabit (Rancheria del Corral), and the Francisco Reyes rancho in the Encino (San Fernando) Valley were examined. The Reyes site was recommended and chosen.[7] Mission San Fernando was formally founded by Fr. Lasuen September 8, 1797. This shortened the gap to about sixty intervening miles between Mission San Fernando and Mission San Buenaventura, whose field of activity extended only to Sespe Creek, less than one half the distance. Between the Sespe and San Fernando, there was a gap of some thirty miles, encompassing some twenty Indian villages or rancherias, and possessing a twenty mile stretch of fertile land through which flowed the Santa Clara river. Mission San Fernando had to contribute to the upkeep of the Presidio at Santa Barbara, from whence came the soldiers of the Mission Guards, and the civil administration. Contributions were bulky, grains, beans, soap, tallow all of which were difficult to pack over the mountains. A productive plant on the Santa Barbara side of the San Fernando mountains would have no transportation problem, it being down hill practically all of the distance to the Presidio. Also there was an adjacent back country of tremendous scope, which could provide excellent grazing for mission herds. At the beginning, Mission San Fernando simply acquired that entire headwater area of the Santa Clara River, easterly from Piru Creek, and called it "Rancho San Francisco." There were people who saw possibilities for personal gain in that ownership. In 1804, the Mission was vigorously protesting the grant of Camulos, at the westerly limit of Rancho San Francisco to one Francisco Avila.[8] The protest was successful. Mission action was stimulated, however and, at Chaguayabit, Mission San Fernando proceeded to build their Asistencia at the precise site originally recommended by Fr. Crespi for the proposed Mission Santa Clara. (Ed. Note: Per Johnson, Mission records suggest the estancia, or outpost, was never raised to the status of an asistencia, or sub-mission.) It was on top of the flattish mesa which rises behind Castaic Junction of today.[9] The Asistencia was built of adobe, and was about 105 feet by 17 feet in size.[10] Here, Fr. Munoz may have stopped in October, 1806, on the Moraga-Munoz exploration of the San Joaquin Valley.[11] It not only filled a need as a stopover to break the long walk between Missions San Fernando and San Buenaventura, it was the administrative headquarters of rancho activities, and training school for local neophytes, who, of course, furnished the labor for maintenance and operation.

It is doubtful if Mission San Fernando mixed neophytes from Encino Valley with those of the rancho, for there were cultural boundaries at Sespe Creek and San Fernando hills. Between these boundaries, language dialects and customs inter-mixed.[12] With the Asistencia practically sitting on top of the local Indian villages, Mission influence must have spread rapidly. Personal rights of the native Indians were non-existent. The Missions had to have labor to till the fields, tend the livestock, clear the land, prepare food for the help. Presidio economic overlordship made requisite training of cobblers, seamstresses, blacksmiths, tailors and muleteers. Adobe brick had to be made. Crushed shell, abundant in the local hills, had to be brought in, its admixture with adobe making the brick practically impervious to water. Tiles for floors and roofs had to be burned. Naturally, tribal customs were forced to give way to the Mission system. From contemporary witnesses, it is gathered that whipping, stocks, and starvation were the usual method of enforcing Mission disciplines.[13] Some time in those earlier years, the medicine men sorrowfully gathered together the previous symbols of their religious ritual. It must have been at night that their procession sadly climbed the steep ridges of the San Martin Canyon area. Ritualistically, they then deposited their treasured traditional regalia and retraced their steps. By some quirk of fantasy, that depository was an open cave, within plain view of the taskmasters at the Asistencia, although distance and rugged backgrounds veiled the tomb.[14] By 1813, Rancho San Francisco herds had increased. Fencing became necessary to keep the cattle from other mission ranches out and the home stock in. The ruggedness of the Pass through the San Fernando hills became an asset, for at the narrow outlet of Grapevine Canyon, a single bar, from side to side, was all that was needed. At the Piru creek, a fence was built from hill to hill, across the river bed. The boundary line between San Francisco and Triunfo ranches was fenced.[15] On the eastern rancho boundary, by "Taburga Tobinga,"[16] an Indian village, an irrigation canal was dug and a small dam built.[17] Indians were not necessarily universally mistreated. The Fathers also had problems, most of them stemming from the Presidio. In 1821, Fr. Ybarra, at Mission San Fernando, writes "el Commandante de la Guerra" at Santa Barbara Presidio answering a requisition for 80 fanegas of grain, with 29 fanegas only, "all that was available."[18] Again, 1825, answering Presidio requisitions, Fr. Ybarra writes, I received your official note asking for $300 worth of soap. To this, I must say, that there are $30 to $40 worth of that article for none has been made this year and very little the last. There are on hand 100 fanegas of beans. Of this quantity, 25 to 30 are necessary for the guards, 10 must be deducted for the tithe, 16 are to be forwarded to the Presidio at Santa Barbara. That leaves 44 or 49 for the Indian creditors, the real owners, those who picked them, first on account of the labor and care, and then on account of the punishment subjected to.[19] Spain was expelled from Mexico in 1821. Missions could no longer appeal over the heads of Mexican authorities to Spanish administrators. The very background has changed. Trend was "Mexico for the Mexicans," locally translated as "California for the Californians." Today it would be called "Nationalism." Expulsion of Spain was hardly completed, when Carlos Carrillo made an unsuccessful attempt to denounce Camulos rancho, westernmost portion of Rancho San Francisco. Was that attempt in the mind of Fr. Ybarra, when he wrote Carrillo in April, 1825, That one should serve and respect him who is of benefit is very proper and just; but that one should feed him who not only does not protect, but positively destroys, requires a stout heart. In effect, what benefit do I receive, or have I and the Mission received from your Presidio? What damages, on the other hand? Incalculable. Yes, yes, if the Presidio did not exist, I could figure on my labor and toil. In that case, I should mind neither the Tulares nor the Sierras, the refuge of wicked men. The second Sierra, or bawdry (Alcabuetaria), your Presidio it is that annoys me. If a low man should behave in a low manner one should not be surprised; but that men who regard themselves as honorable act thus, this is what stuns. Later, in this letter, Fr. Ybarra intimates that soldiers ought to work and raise grain and not live by the toil of the neophytes whom they rob and deceive for "the liberty which you hold up to these unfortunates is nothing more than slavery which contents only a few fools."[20] The above quotation gives an intimation of what the missions were currently thinking of the civil government. It is equally possible that the Presidios considered the Missions a cheap supply source. What did the Indian think? In 1813, an "Interrogatorio" to Mission San Fernando answered that question. In the words of Fr. Munoz "At present there is not observed any aversion for either Europeans or Americans, rather only a supreme indifference" (by the Indian).[21] Incidentally, Mission San Fernando plus Ranch San Francisco had brought El Camino Real to its original path, that of the Sacred Expedition, in spite of the mountain gradients. To stimulate development in colonial possession, if the lands north of Mexico's present boundary may be so described, the Mexican Congress of 1824 legislated encouragement for land settlement. All Grants of national lands were limited to eleven square leagues (one league to be irrigable, four available for farming, and six for pasturage). There could be no absentee ownership, transference to any ecclesitastical body, and veterans had preference rights. A square league contains 4,439 acres. That may seem a generous land allowance, but at that date there was no cash crop excepting hides and tallow. In Southern California, from 50 to 100 acres is frequently necessary per head of grazing stock, if the animal is not going to starve. Maybe a couple of times within a year, and English or Boston trading vessel would come up the coast with merchandise which they bartered for hides and tallow. The money those ships left behind them, was practically all the money there was in local circulation. Even that amount of trade was against Mexican Laws. The Mexican colonization promotion laws were in operation by 1828. Consider the Californian background. As Mr. Shinn points out "when the Missions were first established (under the Laws of the Indies), about 15 acres was allotted to each one; but lands were never surveyed and they gradually extended their bounds until they virtually laid claim to nearly the entire region." The term Mission once meant only the church town with gardens and orchards near it, soon came to include extensive tracts over which cattle, horses and sheep owned by the establishment were allowed to roam at will.[22] Two generations of Californians by birth had developed. They were land hungry. Families were numerically large. California's entire economy was based upon cattle requiring 50 to 100 acres of land per animal. Locally, the situation was clear. Mission San Fernando Rancho claimed over 138,000 acres, nearly all being valley lands. Rancho San Francisco, by a general conception of boundaries, included over 100,000 acres and was also claimed by Mission San Fernando which, as of 1832, recorded only 782 Indian converts at the mission — also 7,000 cattle, 600 horses, and 60 mules.[23] In effect, Government had set up methods for disposal of lands that did not exist — if mission claims were allowed. There could be but one outcome to this clash of interests, between the rapidly increasing population and static holdings of so much for so few. In 1833, the Mexican Congress passed the bill for secularization of the missions. In October, 1834, Lieut. Antonio del Valle was commissioned to take over Mission San Fernando by inventory from the incumbent Padre, Fr. Ybarra.[24] He was paid $800 annually. In March, (1837) "Valle, highly praised by Fr. Duran, was succeeded by Antastasio Carrillo."[25]

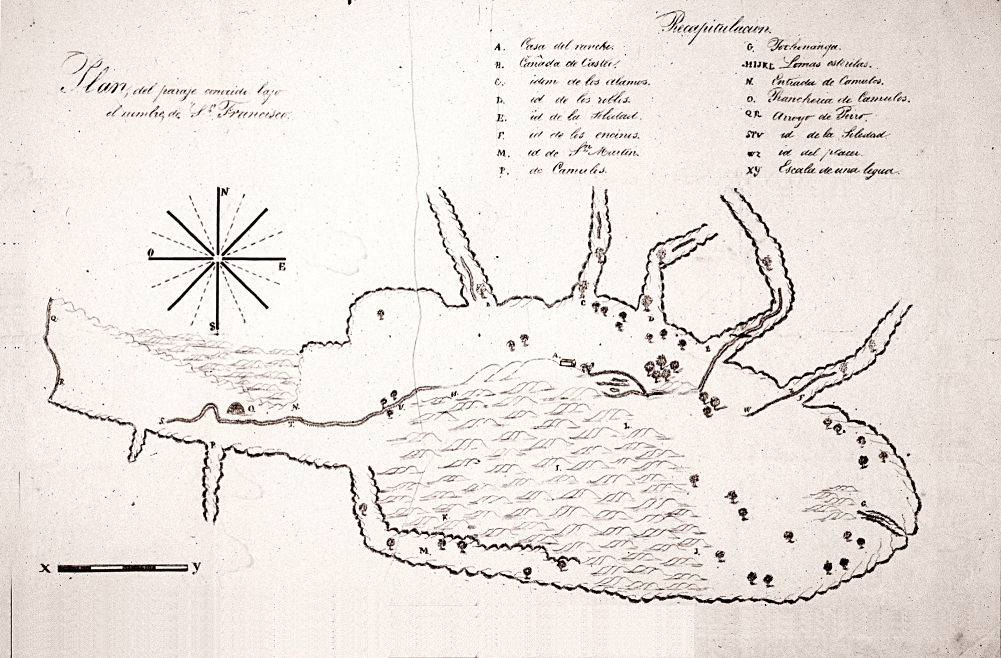

Mission San Fernando was in the Santa Barbara district. Its administrator would therefore pass through the entire length of Rancho San Francisco going to San Fernando. Lieut. del Valle possessed therefore an intimate knowledge of Rancho San Francisco. In 1837, he asked Don Pablo de la Guerra to draw a map (Diseno), of the Rancho from verbal description.[27] The exact current status of the Rancho is a little clouded. It might possibly be that, as of early 1824, all or possibly only the Camulos portion of Rancho San Francisco was being utilized by the del Valles for grazing purposes under some sort of grant or permission from authority. On the other hand, the report of William Hartnell, auditing the missions in 1835, might indicate that as the date the Rancho became individually owned. Don Antonio del Valle petitioned Governor Alvarado for the Rancho January 22, 1839, the petition was granted with the usual restrictions — that no part could be alienated by gift, mortgage, or other encumbrance. The rancho could be enclosed but no existing rights of way could be closed. Grantee should at once solicit the judge to establish rancho boundaries, to take physical possession of the land, and the judge should advise the government of the number of square leagues granted. An unsuccessful protest was filed by Fr. Narciso Duran, Prefect of the Missions of the South of the College of San Fernando of Mexico in Alta California as of February 5, 1839. In a further petition of Don Antonio del Valle, April 5, 1839, for grant in property,[28] there is definitely claim that his right dated from about 1825, with further rights as of 1833. The Mission Asistencia became the first del Valle rancho home, although resentment of the Indians to the grant made it unusable for a short time.[29] Don Pedro Lopez, a relative of del Valle's second wife, Jacopa Feliz, assisted del Valle in driving up some 600 head of cattle, mares, and horses from Rancho San Pedro.[30] Wheat was planted in the cienaga below the house. The family moved into immediate possession and residence. June 12, 1841, Don Antonio del Valle died, mourned by his widow, two children from his first marriage, and four children from his second marriage. Shortly thereafter, the widow was married to Don José Salazar. Camulos Rancho was part of Rancho San Francisco grant. Yet it seems always to have been considered locally a separate entity, and was so referred to, always associated only with Don Ygnacio del Valle.[31] Possibly, as the oldest son, already mature, it was understood that Camulos was to be his portion, even though the estate of Don Antonio was not as yet partitioned. Traditionally, however, it was from the old Asistencia, now the rancho home, that Francisco Lopez and his two friends, Manuel Cota and Domingo Bermudez, left the morning of March 9, 1842, on their way to what became the first authenticated gold discovery in California. Whether the first gold discovery or not, it definitely led to the settlement of the first mining camp in California, at Placeritas Canyon, near the easterly boundary of the yet unsurveyed Rancho San Francisco.[32] In the Spanish Archives, at Sacramento, California, will be found the following Petition: To His Excellency the Governor The Citizens Francisco Lopez, Manuel Cota and Domingo Bermudez, residents of the Port of Santa Barbara, before Your Excellency, with the utmost submission appear saying His Divine Majesty having granted us a Placer of Gold on the ninth day of March last, at the place of San Francisco, appertaining to the late Don Antonio del Valle, distant from his house about one League toward the south, we apply to Your Excelency to be pleased to decree in our favor whatsoever you may deem just and proper forwarding herewith the specimens of said gold. Wherefore we pray to Your Excellency to be pleased to give us the respective permission to undertake therewith our labors jointly with those who may wish to proceed to said work. Excuse the use of common paper in default of that on the corresponding stamp. Santa Barbara April 4th, 1842 Franco Lopez The foregoing is quoted in extenso because it must represent the first attempt at mining location notice in California. The archives show no answer to the petition. What happened next is apparent from the following quotation. The discovery site was certainly within the generally accepted limits of the grant. Trespassing quickly became a major problem to the land owners, and Don Ygnacio del Valle petitioned the Ayuntamiento at the Pueblo of Los Angeles for relief which, as shown, was immediately forthcoming. This court has been informed that they continue to prospect in the gold fields near you, and that, in fact, a number of people are gathering at this place, and in order that this work may proceed in an orderly fashion, I have appointed a magistrate for that place in order to keep law and order, and when he is absent, due to business affairs, Mr. Franco Corrella will be in charge of the place. You will make this decision known to those who are staying there and that your court will be in charge of criminal and judicial cases and this office will handle civil and state affairs in order that we may issue the necessary orders. You will take special care that, as soon as the discovery is made, you will notify this office immediately so that we can establish what each one is entitled to and what municipal rights should be established; and if you have already had reason to do this, you will notify us of it also. As for the sale of liquor and such, which the Community has established, the Laws of the Town will be observed first and be careful to have good reason before infringing upon their jurisdiction. As for the eight dollars which you collect for entering, and for the time they remain there, in consideration of that, they will be in possession and owe it for pasturing their live stock, for water, firewood and even lumber for temporary shelters. This charge seems just, collected only once. As this office is aware that there are now Laws to arrange this affair, I will notify the Superiors of this Department and secure information about the method to be used. You will make known this Deposition to Mr. Sorrella in order that he may acquaint himself with the contents and the duties assigned him. I hope I will have the honor of your acceptance and compliance with the Orders. This occation is presented to me to offer my consideration and appreciation. God and Liberties. May 3, 1842 S. Arguello Senor Ygnacio del Valle Everything considered, the news got around. Del Valle reported to Prefect Arguello in June "only a few miners were not making a dollar per day — the placers were of great extent — no taxes should yet be imposed — there had been 100 miners — now 50, water short — miners would return with the rains."[34] As Mr. Arthur Woodward has pointed out, the Arguello letter is in fact the first Mining Law set up in California.[35]

The gold dust of the placers went to the United States Mint largely via the accounts of Don Abel Stearns. No production record of the camp exists. Bancroft says 2,000 ounces of dust had been shipped by the end of 1843. Due somewhat to Indian raids, from the Mojave Indians, in 1844 the mining camp lapsed, subject to later revivals. In its very early days, the placers were visited by such travelers as Duflot de Mofras, who states that the original discovery was made by a Frenchman, Charles Baric. G.M. Waseurtz of Sandels, also an 1842 visitor, credits discovery to one Melendez, a Mexican, in his "King's Orphan." John Bidwell, writing in 1852, gives discovery credit to Baptiste Ruelle. In 1898, the Bandini History of California, a school text book, names Juan Lopez as discoverer.[36,37] The San Feliciano placer field of 1843 was outside the Rancho boundaries. Discovery is attributed also to Francisco Lopez, the best luck there to José Salazar, soon to be second husband of Jacopa Feliz, who was supposed to have placered $4,300 in one year. In 1843, the title of Camulos was momentarily clouded by a grant to Pedro Carrillo, but examination showing the overlap on the Rancho San Francisco Grant, the Carrillo grant was nullified.[38] There is today a plaque on Highway 6, calling attention to Fremont Pass, giving an erroneous impression that the deep Beale Cut through the hills was it. The Fremont expedition did come through the Rancho, encamping near the del Valle ranch home January 9, 1847. The night of the tenth, they were still on the Rancho, camped approximately at the site of Lyons Station-to-be. On the eleventh, part of the expedition took a direct route over the hills, the artillery and wagons seem to have utilized the Cuesta Viejo, or Grapevine Canyon.[39] The expedition must have resembled a circus parade, coming through the cattle range with its 429 participants, and don't forget the wagons and cannon which had to be let down the steep southern slope with ropes. What a road that was — is. One writer mentions stopping for a night at San Fernando Mission and then spending eight days getting army carts and goods over the mountains.[40]

Three years later, an exaggeratedly contrasting party of foot-sore pioneers stumbled out of the mouth of Soledad Canyon. It was the "Jayhawker" party, what was left of them, ending their tragic trek by way of Death Valley, to the gold fields. Their later descriptions of Rancho San Francisco were slightly on the florid side, understandable, considering the country through which they had come. The party convalesced for a few days in the old adobe milk house, which stood on the slope, slightly above the cienega and below the rancho house, Asistencia. Until World War Two Jayhawkers, and later their descendants, picnicked annually in that cienega.[42] The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo under terms of which California passed into the possession of the United States by purchase went into effect February 2, 1848. It naturally provided for continuity and protection of existing land titles. To bring this condition about, Congress passed a Federal Land Act in 1851, under which commissioners were appointed with authority to review California's private land titles. Three years was allowed for Californians to comply. The Rancho was only a cattle range, accurately speaking. Its isolation seemed to insure protection as such. There was nothing to encourage trespassing. "La Soledad" was an appropriate name for the easterly end of the grant. It is dubious whether a person a day travelled either of the old rights of way, the north-south road to the Tulares, or the east-west take off between Missions. At that time, all of the owners were living in the Pueblo.[43] That was a horrible trail through the Grapevine Canyon to the San Fernando Valley. The road was nearly as bad through San Francisquito Canyon. Westerly, the road to San Buenaventura merely substituted soft sand and river crossings for rocks and grades. The only wheeled vehicle was the springless wood disc wheeled carreta, pulled by oxen. Los Angeles County, which included most of Southern California at that date, had a population of 3,550.[44] The local cash crop was still hides, worth a dollar or so apiece in trade. The curtain was about to rise against a brand new back drop. The fabulous mining boom of '49 was under way in the north. There was a ready market for beef at $15.00 per head. You walked the beef 400 miles, a bagatelle to a California vaquero to whom time was of no importance. In 1851, the Los Angeles Court of Sessions detailed the "Tulare Road to the Mines by the Tulares," by way of ex-Mission San Fernando, Rancho San Francisco, the Canada of Alamos, (San Francisquito), Rabbit Lake (Elizabeth Lake) and on; also "El Camino Real," (existing roads between Missions). Those rights of way had been withheld in the original grant. There was unlimited money and business available in the mining camps and cities of the north. There were pioneer merchants in the sleepy Pueblo, fully conversant with the possibilities developing, accustomed to surmounting handicaps, who intended to get their full share of whatever development might take place elsewhere. Lack of a road could not stop them. The records of the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors, in those formative days show more appropriations, subscriptions, and resultant expenditures to get a passable road to and through Rancho San Francisco northerly, than all of the other county roads combined. That road was going where the big money was. It had a terrific impact on the Pueblo, a greater impact on the Rancho.

The first three cases filed in the new Probate Court of the very new Los Angeles County, U.S.A., were filed for Jacopa Feliz, commencement of many legal actions to settle the estate of the late Antonio del Valle, and perfect the title of Rancho San Francisco, under the new governing laws, that that property might also be partitioned to the heirs.[45] The interested parties were all living in the pueblo. Don Ygnacio del Valle, of Camulos rancho, had just been elected County Recorder. He was living in the home of Don Agustin Olvera. The Salazars were living in their own home.[46] In 1852, the federal machinery was set up for confirmation of the Mexican land titles. In September, Jacopa Feliz, as widow, Ygnacio del Valle, and the other children of the second family of Don Antonio, petitioned for confirmation of title to Rancho San Francisco.[47] Earlier in the year, Don José Salazar had been appointed administrator of the del Valle Estate by the Probate Court.[48] One can wonder if there would have been a different outcome, had Don Ygnacio received that appointment. The probate petition was granted and the estate distributed by undivided portions of the rancho to the heirs. Ygnacio del Valle purchased his sister Magdalena's share for some $6,000.00.[49] The land could not be partitioned before title confirmation. It was simply a chunk of wild land and without boundaries pinned down only by the silver ribbon of the Santa Clara River. The original boundary line of Los Angeles County traversed the northerly boundaries of the Rancho.[50] Later county readjustments left about 11,000 acres, including the Camulos Rancho in that part of Santa Barbara County later to become Ventura County.[51] The westerly boundary was common to Rancho Sespe at Piru Creek. Thence the line ran easterly over the hilltops to "la Puerca," a very narrow gap between cliffs as the foot of the grade is reached, going north, separating the cattle of Mission San Fernando Rancho from those of Rancho San Francisco. On the east there was the Indian village of Tobinga. No near neighbors to the north. In 1853, the Pacific Railroad Survey came down San Francisquito Canyon, climbed back to the divide, and mapped a new route through Williamson's Pass, today called Soledad Canyon.[53] It seemed easier of travel than the older road and later became the more popular — or least worst — of the known routes. This year, Ygnacio del Valle was serving on the first School Committee of the Los Angeles City Council. Eighteen hundred fifty-four was a big year for Rancho San Francisco, that is, for the eastern border. In August, Ft. Tejon was established. Merchants of Los Angeles, who were sending wagon trains to Arizona, Utah, and faraway Idaho, were not missing this new back door market. Within two months a road district, from Los Feliz rancho to San Francisco rancho was formed. The County Board of Supervisors appropriated another $1,000 to improve that terrible wagon road between Mission San Fernando and Rancho San Francisco.[54] The Kern River gold rush really started traffic over the old road to the Tulares. One Francisco Garcia was credited with a season's placer recovery at San Feliciana of $65,000. That included a $1,900 nugget from San Feliciana.[55] An inland stage line was started from Los Angeles to Kern County mines. Somewhere about this time, the Stage Station, later to be called "Lyons Station," came into existence.[56] Major Horace Bell's account of the first stage run over the San Fernando mountains to Rancho San Francisco has been reprinted many, many times. Yet, it is contemporaneous, certainly self explanatory. He says, Banning willed the thing to be done ... and drove the first stage to astonish the aborigines ... the trail over San Fernando Pass was a rocky acclivity ... difficult even by a pack mule ... with a descent of equal abruptness. Standing on the summit ... a precipice of many hundred feet lay before you ... facing about dizzily you wonder how you reached the rocky summit. In December, '54, he sat on the box of his Concord Stage ... reaching the summit ... the question among his nine wondering passengers who had toiled up the mountain on foot was, how the Stage could descend ... He cracks his whip, tightens his lines, whistled to his trembling mustangs, urges them to the brink of the precipice and they are going down!!! rackety, clatter, bang. Sometimes the horses ahead of the stage and sometimes the stage ahead of the horses all, however, going down, down, with a CRASH. Finally the conglomeration of chains, harness, coach, mustangs, and Banning were found in an inextricable mass of confusion — contusions, cracks and breaks ... piled in a thicket of chapparal at the foot of the mountain. "Didn't I tell you?" said Banning, "a beautiful descent, far less difficult than I had anticipated." However, Banning sent back a courier in hot haste, urging Don David Alexander to send fifty men immediately to repair parts of the road which he had, in his descent, knocked out of joint.[57] This marks the arrival of the first stage at Rancho San Francisco. Honestly now, didn't Major Bell have a wonderful control of words? Those old tracks, up precipitous faces of solid rock are so obviously impossible to travel, when viewed today, one can hardly believe the Butterfield and Telegraph Stages could have used that road — but they did. As described, the road could seemingly not have attracted any but the most urgent traffic, urgency meaning profitable. There is no count of the wagons that tipped and dumped their loads down those steep hillsides. Rumors have even come down that a wooden barrel of flour is tough to salvage from a canyon bed. In 1856, the earthquake flattened Ft. Tejon. (Ed. Note: The date was January 9, 1857.) Its need as a fort had largely passed, and the new Kern River mining camps were an acceptable substitute for the Tejon trade. A circus tinge broke the monotony of the road to the Tulares traffic the following year, when E.F. Beale began driving his camel tandem drawn buggy from Tejon to Los Angeles. This may have been the year when Francisco Lopez, credited with the gold discoveries at both Placeritas and San Feliciano, now a stockman, told pioneers W.W. Jenkins, W.C. Wiley and Sanford Lyon of the Pico Canyon oil seepages. Kern River, or San Joaquin Valley trade was of major importance to Los Angeles. With all the money and labor so far expended, the pass was still a cork in a transportation bottleneck, a role that it would play for better than another half century. In 1858, recognizing the importance to the Pueblo of the problem, the County Board of Supervisors put out $5,000 in County warrants for road improvements by and through Rancho San Francisco.[58] This was the year that the Butterfield Overland Mail first operated. It carried one passenger, Waterman L. Ormsby, correspondent for the New York Herald. The following quotation from his articles takes the reader from San Fernando Mission through to Rancho San Francisco. The road leading through the new pass is rugged and difficult. About the center of the pass is, I believe, the steepest hill on the entire route. I should just it to be 500 feet from the level of the road, which has to be ascended and descended in the space of a quarter of a mile; ... certainly it is a very steep hill and our six horses found great difficulty in drawing our empty wagon up. The road takes some pretty sharp turns in the canyon and a slight accident might precipitate a wagon load into a very uncomfortable abyss... Eight miles from San Fernando (Mission) we changed horses again at Hart's rancho, having made nearly ten miles per hour in spite of the bad condition of the roads ... from this point the road leads through San Francisco Canyon, 12 miles long.[59] Staging was important, before railroads came. Stage lines are dependent upon livestock and wagons. They could not keep running without stations at rather short intervals. That explains Lyon Station, probably the first white settlement in the area. It was on the Rancho, at today's junction of Highway 6 and San Fernando road, south of Newhall. It was probably opened by Henry Wiley and Jose Ygnacio del Valle in the early Fifties. (Ed. Note: Perkins bases this on the word of an elderly Sarah Gifford, who did not bear personal witness to Wiley's purported ownership. Also note that Jose Ygnacio is not Ygnacio. See fn 56.) Its name changed as did the Station keepers. In 1855 Cyrus and Sanford Lyon ran the Station. In 1858 it was called "Harts," afterwards "Hosmers." In 1861 it was "Fountains." Andrews Krazinsky may have bought the 380-acre property from the Philadelphia & California Petroleum Company in the Seventies.[60] The Station was then known as "Andrews," though operated by Adams Malejewski. He was succeeded by George Dilly who moved the Station down closer to the railroad right of way.

In the Fifties, there was another Stage Station on the Rancho, known as "More's Station," located about where San Francisquito Canyon empties into the Santa Clara River. Later, More went up to the active mining camp at San Francisquito, and the Station was then known as "Hollandsville" in 1860. It was the scene of a small slaughter when three Mexicans attacked the Station killing two men.[61] They were regular stops for the California, later the Telegraph stage lines, for the Butterfield stages, while they ran. Stage schedules showed Lyons Station 8.79 miles from Lopez Station, sometimes called "25 mile," or "Mission San Fernando." It was a junction point for passenger transfer for the stage lines coming down from Santa Barbara and Ventura.[62] In 1858, Surveyor Henry Hancock ran the patent survey of Rancho San Francisco. The original description, from the grant of Governor Alvarado, commencing with the junction of a creek called the Arroyo of Piru or Piraic with the Santa Clara River, thence ascending the said river, including the valley on both sides thereof, up to and including a place called "La Soledad" was rather generalized and could be interpreted as granting over 100,000 acres, in contravention of the Mexican Land Laws governing, which limited grants to eleven square leagues. As was the custom, the grantees chose their desired areas, which the surveyor trimmed to fit the laws and stay within the limits there imposed. As of May 10, José Salazar borrowed $8,500 from William Wolfskill at 1½ per cent per month interest, payable quarterly or to be compounded, pledging six of the grant's eleven leagues, in Los Angeles County.[63] Californians were in a bad position. Under the new (to them) United States laws, they had to hire attorneys to perfect their land titles, present the case, handle the appeal, pay for surveys, and incidentally to probate an estate. Except for the short time during the Gold Rush of '49, when cattle sold for $15.00 a head, in the north, Californias seldom had cash. The country had been sparsely settled with a "beef and barter" economy. The influx of United States citizens upset local customs and local laws. One is reminded of the fate of the prior land holders, the Indians and the Missions. Camulos continued a pastoral existence contrasting positively with that area traversed by the road to the mines. In 1859, mining activities beyond the grant borders continued building up, meaning more people passing on the road, or, "traffic." Inside the Rancho San Francisco, conditions were not good. Some "50 valuable horses belonging to Don José Salazar" were stolen by Indians. Salazar evidently felt the pinch, for the mortgaged Jacopa Feliz equities in the Rancho were deeded to Ygnacio del Valle, consideration $1,000. In 1860, Salazar was again borrowing and mortgaging the properties already mortgaged and deeded. The Rancho Survey of Henry Hancock was approved, however, issuance of the patent was not requested.[64] Ygnacio del Valle was appointed Judge of the Plains for San Francisquito.[65] A new turnpike road from San Fernando to the Santa Clara River was authorized, but never built. The telegraph line coming down from San Francisco, built past Fountains Station.

In 1861, Don Ygnacio del Valle moved to Camulos, there to stay.[66] For twenty years, no one had been more prominent than he in county life. At Camulos, he would revive and carry on the pastoral life of early California. At this date, he is credited with the ninth largest herd of cattle in Los Angeles County.[67] In 1862, a 20-year franchise was granted for a turnpike from ex-Mission San Fernando to the Arroyo de Santa Clara, under which E.F. Beale immediately commenced the deep cut through the crest of the San Fernando mountains.[68] (Ed. Note: The contract first went to Andres Pico, who failed to perform; it was subsequently awarded to Beale. See V.S. Ripley.) Don Jose Salazar now quit-claimed the mortgaged, deeded rancho equities of his wife again, this time to a couple of Los Angeles lawyers.[69] Wolfskill's mortgage, plus the interest of 1½% monthly, compounded quarterly, underwent foreclosure, and he received a sheriff's deed in September for the undivided six leagues of Rancho San Francisco in Los Angeles County.[70] The next year, Beale's cut being completed — (Ed. Note: Beale finished the initial work in 1863 but the county supervisors didn't accept it as fulfilling the contract. They ordered him to perform additional improvements, which he completed in 1864. See V.S. Ripley.) — the County Supervisors set the allowable charges[71] — they were:

The toll house was opening just in time for the Soledad mining boom just coming into prominence. On the Rancho, Wolfskill's attorneys were again suing for foreclosure. In 1864 a second sheriff's deed was issued to Wolfskill[72]. Something else was happening just over the southerly line of Rancho San Francisco. In 1865, Ramon Perea filled his canteen with the liquid from certain seepages in Pico Canyon. Perea rode over to San Fernando, where Dr. Vincent Gelcich identified the canteen's contents as oil.[73] The discovery, which it certainly was not, such seepages being known to,and utilized by local Indians from time immemorial was not within rancho lines, but a mile or so out. Commencing in 1865, deeds to undivided portions of Rancho San Francisco appear in the records from the various heirs of Antonio del Valle in favor of Ygnacio del Valle, incidentally including the Wolfskill equities, culminating in a deed from Ygnacio del Valle to Thomas R. Bard, as of March 18 of the Rancho San Francisco lands in the County of Los Angeles. Consideration was $47,519.71.[74] These lands immediately passed to the ownership of the Philadelphia & California Petroleum Company, in other words to Thomas Scott.[75] It will be recalled that Rancho San Francisco was a Mexican land grant under Mexican laws and could not exceed eleven square leagues. The Hancock Survey of 1858 was just under that limit and was satisfactory to both the United States Government and the land owners. Title had been confirmed, but patent not yet issued. Oil having been found just over rancho borders, the Scott interests brought in another surveyor who did right well, turning in a survey that included 102,025 acres. Peculiarly, the new oil prospects were included therein.[76] This second survey was based on the theory that Mexican grants, having been made and described by landmarks, said landmarks must govern the boundaries, regardless of amounts of included acreage or governing Laws. The Scott interests filed suit to set aside the Hancock survey, and substitute therefore the George H. Thompson survey of 1865.[77] In 1866, mortgage was drawn to a trustee, securing a bond issue, on the Philadelphia & California Petroleum Company, conveying an undivided 13/15 of Rancho San Francisco lands within Los Angeles County for $25,000.[78] Aroundabout, the oil seepages of Wiley Canyon were being skimmed, and the oil salvaged shipped to the Metropolitan Gas Works, in San Francisco. The Havilah stage was running on the road to the Tulares.[79] As usual, a subscription was being taken up in Los Angeles to improve the Rancho roads, this time with accent on San Francisquito Canyon, the Beale toll road having finally unplugged the pass.[80]

No picture of Lyons Station is known, a contemporary description tells of a well constructed frame building, 30' x 60', answering the purpose of a store, postoffice, telegraph office, depot and tavern. There was also a large stable and a cottage half hidden in the mountain oak. The site is marked today only by the old graveyard. The Handbook & Directory of 1868 lists 20 heads of families at Lyons Station; at Soledad mining camp, 60 were listed, at Placeritas, eight.[81] Sanford Lyon is credited with "spring poling" an oil well at the site of the future CSO No. 4 well, in Pico.[82] In 1869, the Soledad School District, which included Rancho San Francisco, was formally separated from the San Fernando school district.[83] The following year, Rancho San Francisco was finally partitioned by one L.F. Cooper, to facilitate apparently financing of Scott's Oil Company, who were issuing another $50,000 of bonds under trust indenture.[84] Scott interests claimed an undivided 19/21 of the Rancho interests by purchase, having acquired all but those of Don Ygnacio del Valle, who continued placidly and profitably operating Camulos rancho, regardless of litigation, mining, petroleum, or the new ideas being brought into California life. The undivided 2/21, carried with it Camulos, legally, formally, and unencumbered. Its 1,340 acres were permanently separated and divorced from the troubled background of the grant. The partition went into effect July 30, over the signature of Pablo de la Guerra, then district judge.[85] It will be recalled that the first Diseno or map of the Rancho had been drawn by Judge de la Guerra in 1837. Political pressure having been unsuccessfully applied, Scott, Parsons and Bard, all interested parties and individually very influential within their respective orbits, finally gave up hope of getting the Thompson survey accepted, and in 1872 withdrew their protest. They accepted a new Thompson survey based entirely on the Hancock survey, and the grant finally went to patent February 12, 1875.[86] In the latter part of 1873, there was a trustee's foreclosure under the bond indenture, and sheriff's deed issued in favor of Charles Fernald and Jarrett T. Richards, Santa Barbara lawyers who later appear as attorneys for Henry M. Newhall and, incidentally, Ygnacio del Valle.[87] As early as May, the following advertisement was appearing in the Ventura paper: RANCHO SAN FRANCISCO Contains 48,000 acres and is situate on the river Santa Clara. The lines of the Southern Pacific and the Atlantic and Pacific Railroads are surveyed through portions of this rancho. It contains a large quantity of ARABLE BOTTOM LANDS Prices of Arable Land $6.00 to $12.00 per acre Real Estate Agent Roundabout the rancho, the chief current items of interest would be the revival of the San Feliciano mining camp.[90] A weekly stage line from Los Angeles to the new Panamint Mining District was inaugurated via San Francisquito Canyon.[91] By 1874, it could be truly said that the birth of the petroleum industry of the West was taking place just south of the rancho lines and also to the west. Remi Nadeau was back freighting from railhead at San Fernando to the Cerro Gordo mines. The Vasquez gang held up the stage in Soledad Canyon.[92] Soledad mining camp was practically inactive, but about the old mining district, settlers were homesteading and farming. The Telegraph stageline was running from Caliente railhead to San Fernando railhead over the old road. The Lyons Station stage line was running from Ventura. The first postoffice on the Rancho was opened at Lyons Station.[93] It didn't stay long. Within the year it was moved to a new location closer to the railhead right of way ,and the postoffice name changed to "Andrews Station" in June.[94] The following month, construction of the Newhall railroad tunnel was begun, length to be 6,940 feet, for passage of the approaching railroad tracks. The first oil refinery was built at old Lyon Station.[95] T.A. Bard's newspaper advertisements paid off when Rancho San Francisco was deeded to Henry M. Newhall, consideration $90,000, January 15, 1875.[96] What a difference a railroad could make, for that matter, even a road. Here, at the easterly end of old Rancho San Francisco tied to the world of that day by the road to the Tulares everything happens. In 1876, a new townsite known as "Newhall" is opened on the railroad lines, but it was located at the site of today's "Saugus."[97] The town lots at the Saugus site failed to sell. Every time there was a prospective buyer, there was a sand storm. A two-year losing struggle of the Pacific Improvement Company ended when George Campton picked up his store and moved it about three miles south, to the new Newhall. The railroad station was opened with John T. Gifford acting as agent. The cave-ins and the explosions which marked the tunnel construction ended. There was a rumor that Mr. H.M. Newhall was projecting a big hotel, a store, and that the brush-covered acres of the river bed would be cleared, plowed, planted for miles. The new town already had six buildings, brought from the old Saugus site.[98] At the westerly end of the rancho, at Camulos, the pastoral life prevailed. There was a change. Sheep had been added, for Ygnacio del Valle shipped six bales of wool from the Ventura wharf.[99] There was a stage running past nearly every day, but "the road between Ventura and Newhall is the worst neglected piece of road in the State."[100] What does one do with a stage station, when the stages go away? HOTEL AT LYONS STATION The Undersigned has opened a fine and commodious hotel at Lyon's Station, about a half mile from the Railroad, where he can accommodate guests in the most satisfactory style. CONVEYANCES belonging to the Hotel will always be in waiting at the cars. The location is one of the most picturesque and healthiest in Southern California and there is good hunting in the immediate vicinity. Prices very moderate. George R. Dilly[101] Thus passed another landmark. The Ventura stage was robbed, three miles out of Newhall.[102] A.P. More, as stockholder, in the Philadelphia & California Petroleum Co,. sued both Bard and Newhall, on the foreclosure of the Rancho liens.[103] The Star Oil Works started an oil refinery at Andres Station.[104] Ten Chinamen with rockers head into San Francisquito.[105] Driving of the Golden Spike at Lang completes the railroad.[106] Newhall Elementary School District was organized,[107] a 10 x 12 board and batt structure on the grant, just south of the junction of Pico Road and Highway 99, on site loaned by Sanford Lyon. (Ed. Note: Perkins bases this information on word of mouth from Addi Lyon, 1873-1951. Addi and other children were probably schooled, at first, on the Lyon ranch in the location described — possibly under today's Interstate 5 freeway — but the first official schoolhouse was built in the "new" Newhall in 1879.) The oil fields of Pico began their development under D.G. Schofield [sic] and Alec Mentry, heading the California Star Oil Company and the Pacific Coast Oil Company. All this, and a townsite too. The following year, the Southern Pacific depot, the George Campton mercantile store, some four other small buildings, and the name even, were picked up, loaded, moved three miles southerly to the new and final location of the town of Newhall.[108] At the other end of the grant, Ygnacio del Valle lived the life of a successful gentleman, surrounded by his beautiful orchards, his prosperous productive vineyard, groves of eucalyptus and gardens, his usual crops of corn, barley, wheat. In one year, his vineyard produced 40,000 gallons of wine and brandy.[109] Since 1804, Rancho San Francisco had dominated the upper Santa Clara valley. It would no more. Even its identity had been lost. By the irony of fate, Camulos rancho would live as such in song, story and fact, but Rancho San Francisco would henceforth be known only as the "Newhall Rancho." NOTES 1. Crespi's Diary is reprinted in "Palou's New California" by Bolton, Berkeley, 1926. Diaries of Portola and Constanso are reprinted in Vol. 2. "Pubs. of the Academy of Pacific Coast History," Univ. of Calif. Press, 1909-10. 2. Crespi's Diary, "Palou's New California" by Bolton, Berkeley, 1926. Vol. 2, page 141. 3. Ibid. 4. Ibid., Vol. 2, page 311. 5. Ibid., Vol. 3, page 233; Vol. 4 page 331. 6. "On the Trail of a Spanish Pioneer" by Elliott Coues, Vol. 1, page 264. 7. "San Fernando Rey," Fr. Engelhardt OFM, pages 7-9, "Franciscan Press Herald," Chicago, 1927. 8. Ibid., page 20. 9. Ibid., page 16. 10. A Dig at the site in 1935, indicated five rooms, those for storage and dormitory use having whitewash interior. The living quarters had tiled floor, and whitewash walls. Roof was of Mission tile, burned at kiln easterly end of rear building. This rear adobe structure, paralleling the larger front building, apparently divided into small rooms for trades, cobbler, smith, sempstress, etc. There was little recovery from the dig, which was abandoned after vandals ruined the tile floors and remaining adobe walls searching for Mission treasure about 1937. The buildings stood on the high mesa overlooking Castaic Junction. (Ed. Note: The "dig" was not performed by archaeologists, but by Perkins and companions.) 11. "San Fernando Rey," page 19. 12. Letter of Dr. John P. Harrington, Senior Ethnologist, Smithsonian. 13. "Letters on the Indians," by Hugo Reid, 16 to 22. 14. Storage was in "Bowers Cave" in San Martinez Chiquito, named for Stephen Bowers, early day California scientist. In 1884 he sold some 38 specimens of local basketry, feather work, musical instruments, etc., to Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, at Harvard University, where they are today. 15. "San Fernando Rey," page 20. 16. "Taburga" or "Tobinga" is named as Indian Village approximately on easterly boundary line of the Rancho in depositions in Expediente Rancho San Francisco, Case 318, National Archives. To date, have not been able to locate site. 17. "San Fernando Rey," page 40. 18. Ibid. 19. Ibid., page 41. 20. Ibid. 21. Ibid., page 28. 22. "Mining Camps," Charles Howard Shinn, pages 61-63. New York, 1947. 23. "San Fernando Rey," page 102. 24. Ibid., page 50. 25. Bancroft's "Works." Vol. 20, page 648. 26. Antonio del Valle came to California from Dept. of Jalisco, Mexico, as Lieut. in Company of San Blas, 1819. Family wealthy. In 1824, made profitable trading with Indians at San Emilio to about $14,000 in gold (Bancroft, Vol. 25, p. 38). Served in many civil and military posts. Appointed Administrator Mission San Fernando 1835. Commandante at Santa Barbara Presidio 1838. Married, for second time, Jacopa Feliz, by whom five children. Ygnacio and sister Magdalena, by first wife before coming to Calif. Original grantee Rancho San Francisco, 1839. d. 1841. 27. Deposition Don Pablo de la Guerra, Expediente Rancho San Francisco, Case 318, National Archives. 28. Petition of Don Antonio del Valle, April 5, 1839, for "Grant in Property." Spanish Archives in Sacramento. Original in National Archives Expediente of Rancho San Francisco. Many original documents destroyed in San Francisco fire, including the original del Valle petition for grant as of 1838. 29. Deposition Jose Maria Covarrubias, Expediente Case 318. 30. Deposition Don Pedro Lopez, Expediente Rancho San Francisco, Case 318, National Archives. 31. See Thompson & West, "History of Los Angeles County," reference to Camulos, page 48. Oakland, 1880. 32. "Pre-Marshall Gold in California," by E.T.H. Bunje and James C. Kean, Bancroft Library, Berkeley, Calif., is interesting to students in this field. 33. Bancroft shows Santiago Arguello as Prefect in Los Angeles 1840-1843, and Francisco Sorella was a Sonoran who worked in the placers locally and disappeared in the Gold Rush of 1849. Original is in Bancroft Library. This translation by courtesy Miss Lois Phillips of Wm. S. Hart H.S. 34. Bancroft, Vol. 21, page 631. 35. Mr. Woodward was Curator of History at L.A. County Museum for many years. 36. "History of California," by Helen Elliott Bandini, American Book Co. 1898, page 147. 37. In 1930, Ramona Parlor No. 109, the La Mesa Club and the Kiwanis Club of Newhall-Saugus dedicated a plaque to Francisco Lopez at the discovery site. "His associates' names seem to have been lost off.) A plaque was set on "The Oak of the Golden Dream" which has been stolen. The site is now a State Historic Park, operated by Los Angeles County. This was dedicated May 26, 1956. One can pleasantly dream under the Oak of the Golden Dream, or picnic in beautiful oak groves. Gold can be panned, but not profitable. 38. Bancroft's "Works," Vol. 21, page 642. 39. Fremont's "Memoirs" refer to a Pass of San Bernardo, of which there isn't any. Until Mrs. Fanny Vandegrift Sanchez found and translated, in Bancroft's Library, a MS of one Jose E. Garcia of the Californian group assigned to the harassing of Fremont's Expedition, route tracing seemed hopeless. In Sr. Garcia's words "the next day in the morning we set out (from Sespe, Jan. 8, 1847) for San Fernando Mission ... we spent the night there. The following day we went as far as the hill of San Francisquito ... from the top of the hill mentioned we made out Fremont's camp, a very short distance below in the valley ... (future site of Lyons Station). Here, within sight of the enemy, we camped and remained until seven in the evening when we returned to the Mission." There is but one place on the crest of the hills answering the requirement of visibility of the Mission and the camp site. Corresponding entries in Lieut. Bryant's "What I saw in California," D. Appleton & Co., 1848, pages 387-391 dovetail with Garcia's descriptive entries. 40. "Journal of John McHenry Hollingsworth," p. 50. California Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. 1., No. 3. 41. "Death Valley in '49," by William Lewis Manly, San Jose, Calif., 1894, pages 175-258. Manly is emerging from the terminal of Soledad Canyon — "There was, before us, a beautiful meadow of a thousand acres (Saugus to Castaic Junction) green as a thick carpet of grass could make it, and shaded with oaks, wide branching and symmetrical, equal to those of an old English Park, while all over the low mountains that bordered it on the south and over the broad acres of luxuriant grass was a herd of cattle numbering many hundreds, if not thousands... "As we went along, a man and woman passed us ... the woman had no hoops or shoes and a shawl about her neck with one end thrown over her head as a substitute bonnet ... the man had sandals on his feet, with white cotton pants, a calico shirt, and a wide rimmed conical colored hat... "A house on higher ground soon appeared in sight. It was low, of one story with a flat roof, grey in color, and of a different style of architecture from any we had ever seen before." The building is, of course, the Asistencia of 1804, repaired and returned to use by Don Antonio del Valle as his rancho home in 1839. The Jayhawkers, however, convalesced in the milk house, down the slope but above the willows. 42. "Jayhawker" John B. Colton to Mr. E.H. Bailey, Rancho San Francisquito, Surrey P.O. Los Angeles County, Feb. 28, 1903. Letter in possession of Mrs. Bertha Bailey Taylor. 43. "Census of City and County of Los Angeles for the year 1850," Los Angeles, 1929. 44. Ibid. 45. Abstract of Title, California Title Guaranty Company. 46. "Census of City and County of Los Angeles for the year 1850," Los Angeles, 1929. 47. Abstract of Title, California Title Guaranty Company. 48. Ibid. 49. Ibid. 50. Chap. 15, Statutes of California. 51. County Boundary changes detailed Thompson & West, Oakland, 1880 p. 47. 52. Deposition Antonio Maria Lugo, Case 318 (Rancho San Francisco). 53. "Pacific Railroad Surveys," Washington 1856, Vol. 5, p. 28-9. 54. Minutes of L.A. County Board of Supervisors, Aug. 11, 1854. 55. "Historical and Biographical Record of Los Angeles and Vicinity," L.M. Guinn, Chicago, 1901, page 111. 56. The late J.T. Gifford once told writer that the stage station was opened by Henry Wiley, son-in-law of Andres Pico, and Jose Ygnacio del Valle, a younger step-brother of Ygnacio del Valle, in very early Fifties. 57. "Reminiscences of a Ranger," by Major Horace Bell, p. 322-4, Los Angeles 1881. 58. Minutes of L.A. County Board of Supervisors, Aug. 4, 1858. 59. "The Butterfield Overland Mail," San Marino, Calif. 1954. 60. The Kraezinsky [sic] equity apparently was extinguished by the mortgage foreclosure of the California & Philadelphia Petroleum Co. [sic], 1873. 61. Los Angeles Star, Sept. 15, 1860. 62. Ibid., Jan. 5, 1861. 63. Abstract of Title, California Title Guaranty Co. 64. Los Angeles Star, September 1, 1860. 65. Ibid,. February 25, 1860. 66. Ibid., April 20, 1861. Ygnacio del Valle joined his father in California in 1825. In 1828 entered military service on the staff of Gen. Echeandia. Was captain and chief custom house officer at San Diego until 1833. Served at Monterey until 1836. Tried to stay out of the Castro, Alvarado, Gutierrez embroglio [sic], not too successful although he had separated from the military, so to do [sic]. Discharged from Army 1840. With Jose Antonio Aguirre, received grant of the 97,000 acre Tejon rancho in 1843. Among his many civic and military services, was Commandante in secularization of the missions in 1834. In 1843, was Juez, or Judge at mining district of San Francisquito. In 1845 member of the Junta. In 1846 served as treasurer of department until U.S. took over. In 1850 served as Alcalde of the Pueblo. At the first election under new laws, was elected County Recorder. Served as assemblyman in 1852 and 1856. He was a man of education and ability, very successful. In connection with his inheritance, Camulos rancho, he successfully battled and defeated such men as Tom Scott, H.M. Newhall. The foregoing is gathered from many sources, (H.D. Barrows, Hist. Soc. Annual 1899, etc.) As the background of "Ramona," Camulos may have been the best known rancho of California. 67. "Illustrated History," Lewis Publishing Co., p. 93. 68. Statues of California, Chap. CCLIX. 69. Abstract of Title, California Title Guaranty Co. 70. Ibid. 71. Minutes L.A. County Board of Supervisors, April 4, 1863. 72. Abstract of Title, California Title Guaranty Co. 73. Son-in-law Andres Pico, Ex-Army contract surgeon. In all contemporary writings. 74. Abstract of Title, California Title Guaranty Co. 75. Ibid. This was the Thomas Scott who served as Assistant Secretary of War in the Civil War. With Andrew Carnegie, he made a fortune in Pennsylvania oil. Headed the Pennsylvania R.R., also the Texas & Pacific. 76. "Frauds in Surveys of Mexican Grants," James F. Stuart, Washington, 1872. 77. Ibid. 78. Abstract of Title, California Title Guaranty Co. 79. Los Angeles News, August 11, 1868. 80. Ibid., August 25, 1868. 81. "Handbook & Directory" of San Luis Obispo, Santa Barbara, Ventura, Kern, San Bernardino, Los Angeles and San Diego Counties, L.L. Paulson, Publisher, 1868. 82. "Black Bonanza," by Earl M. Welty and Frank J. Taylor, New York, 1950. 83. Records of Los Angeles County Board of Education. 84. Abstract of Title, California Title Guaranty Co., p. 57-58. 85. Ibid. 86. "Frauds in Surveys of Mexican Grants." 87. Abstract of Title, California Title Guaranty Co., p. 59. 88. Ventura Signal, May 10, 1873. 89. T.R. Bard was, to Ventura County, what such pioneers as Phineas Banning or D.W. Alexander or Don Abel Stearns were to Los Angeles County. Nephew of Tom Scott, represented Scott interests in California. Co-founder of Union Oil Company, pioneer stock man, a United States Senator, promoter of Hueneme harbor. 90. Ventura Signal, May, 1872. 91. Ibid., Nov. 24, 1874. 92. Ibid., Feb. 27, 1874. 93. Postoffice Department Archives. 94. Ibid. 95. Los Angeles Daily Herald, Jan. 1, 1876. 96. Abstract of Title, California Title Guaranty Co., p. 63-64. 97. Site deeded by Henry M. Newhall to the Western Improvement Co., Oct. 16, 1876. S.P.R.R. station opened by John T. Gifford as agent. 98. L.A. County Surveyors Office Records, 1878. 99. Ventura Weekly Free Press, Dec. 25, 1875. 100. Ibid. 101. Los Angeles Express, March 21, 1877. 102. Ventura Weekly Free Press, Jan. 27, 1877. 103. Ibid., Jan. 25, 1877. 104. Ibid., May 26, 1877. 105. Ibid., April 11, 1877. 106. Los Angeles Express. 107. Records Los Angeles County Board of Education, informant, the late Addi Lyon. 108. Feb. 5, 1878, the name was formally transferred to present Newhall site. 109. Ventura Weekly Free Press, February 17, 1878.

|

Location 1928

Ruins

Roof Tiles x2

Story: Rio Santa Clara in Costansó's Diary Perkins Manuscript: Colonization

Junípero Serra (1)

Junípero Serra (2)

Juan Crespí Story

Graves of Serra, Crespí, Lasuen

Serra's Coffin

Serra Cenotaph

Pedro Fages

Fages Marker

Francisco Garcés

Early Afro-Mexican Settlers (Video 2015)

Secularization & Sale, 1830s-40s (Engelhardt 1927)

Vischer 1865

Dedication 1925 x4

Bell at Camulos: Alaska Report 1923

Bell at Camulos (News reports 1923)

Bell at Camulos (Engelhardt 1927)

Pre-Restoration

Index

Actinolite Canoe by Ted Garcia 2012 x4

SEE ALSO:

• Story by Pollack

Description 1873

Kraszynski Sues to Recover Land 1874

Map August 1875

Visit March 1875

Description Jan. 1877

Description May 1877

Lyons Station House

Lyons Station Location 1875-1933

Sanford Lyon

Lyon Boy's Death 1881

Addi Lyon in the News

Sanford Lyon's Grave

Pioneer Cemetery

Pioneer Cemetery Location 1933-1966

Addi Lyon Obituary 1951

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.

Rancho San Francisco designates the headwater of the Santa Clara River, draining the northwesterly portion of Los Angeles County. Geographically, it is a cañada, or narrow valley lying between two mountain chains. The motorist on California State Highway 6 enters the old rancho limit slightly beyond the crest of the Newhall Pass, and leaves the rancho boundaries on Highway 99 near the town of Castaic. If the motorist turns westerly on California Highway 126, by Castaic Junction, he will run out of the rancho boundaries when crossing Piru Creek.

Rancho San Francisco designates the headwater of the Santa Clara River, draining the northwesterly portion of Los Angeles County. Geographically, it is a cañada, or narrow valley lying between two mountain chains. The motorist on California State Highway 6 enters the old rancho limit slightly beyond the crest of the Newhall Pass, and leaves the rancho boundaries on Highway 99 near the town of Castaic. If the motorist turns westerly on California Highway 126, by Castaic Junction, he will run out of the rancho boundaries when crossing Piru Creek.