|

|

Story of Little Santa Clara Valley.

Chapter 2: Colonization.

(Previously) Unpublished Manuscript, n.d. (~1940s).

|

Webmaster's note.

Probably written in the 1940s before the author coined the term "Santa Clarita" (although he continued to use "Little Santa Clara" afterward), this typewritten draft of a manuscript is the earliest known iteration of a portion of Arthur B. Perkins' story of our valley, which he told many times in the pages of The Signal and elsewhere in the 1940s-50s-60s. This 15-page section, Chapter 2, is the only portion of the original known to survive. By today's standards, we'd consider the subject matter to be presented through a colonial lens, written at a time when the valley's first peoples were ascribed to history while, in truth, their descendants were still here. It is what it is. Perkins' contributions to the preservation of Santa Clarita Valley history were profound. Had he not started gathering photos and stories soon after his arrival in 1919, there would have been little local history to pass on to Jerry Reynolds in the 1970s and beyond. The Internet Age has expanded our knowledge of local history with an explosion of new source material; but from the 1940s to the end of the 20th Century, everything we knew fit into the little box created by Perkins. This box. (This and the missing chapters.) Today, this essay is important for a couple of specific reasons. One, Perkins seems to know the location of the Indian village in Newhall (Tochonanga) — knowledge which is now lost. He gives a clue that begs exploration. Two, Perkins says he accompanied Van Valkenburgh (who is credited with the discovery) when in 1935 they found the 1804 estancia on the bluff overlooking the Santa Clara River. Perkins provides details about its construction not known elsewhere. The essay is also perhaps even more important in its totality. Rather than reading through the literary pitfalls that ensnare the author — from his handwritten title for the colonial period, "History Begins," (which leaves us to wonder what he titled Chapter 1), to his reference to "naked Indians" after quoting a Spanish explorer who reported that the local women were clothed, top and bottom — the reader is encouraged to catch them and learn that this was the way our valley's history was presented locally for more than 50 years. Spelling and little else has been corrected. We have "edited in" Perkins' margin notes and inserted some editor's notes of our own in italics.

Chapter 2: History Begins. The people of America are not lucky enough to have the diary of Leif Erikson, nor any of his Norsemen, to tell forever the story of the first landing of white men on the North American continent. Those of the Little Santa Clara Valley are more fortunate, for down to today there exist the day-by-day diaries of Father Crespi, the Franciscan, and Constanso, lieutenant of Gaspar de Portola, to tell of the valley and its inhabitants as they saw them, on August the 8th, 1769. (A diary written at the time and at the place is legal evidence even in a court of law.) The following excerpts are from Bolton's translation of the Crespi and Costanso diaries. From the diary of Father Crespi is taken the following story of August the 8th and 9th, 1769.

Tuesday, August 8. About half past six in the morning we left the place [Tunnel Station, Highway 99] and traveled through the same valley, approaching the mountains. Following their course about half a league, we ascended by a sharp ridge to a high pass, the ascent and descent of which was painful, the descent being made on foot because of the steepness. Once down we entered a small valley6 [over San Fernando Pass to Newhall] in which there was a village of heathen who had already sent messengers to us at the valley of Santa Catalina de Bononia [San Fernando Valley] to guide us and show us the best road and pass through the mountains. These poor Indians had many provisions ready to receive us. Seeing that it was our intention to go on in order not to lose the march, they urgently insisted that we should go to their village, which was some distance off the road; and we were obliged to consent in order not to displease them. We enjoyed their good will and their presents, which consisted of some baskets of pinole, made of sage and other kinds of grasses, and at the side of these baskets they had others for us to drink from. They gave us also nuts and acorns, and were presented with beads in return. They furnished some other guides to accompany us; and we went on by the same valley, arriving late at the watering place, after a march of about four leagues. The country from the village to the watering place is delightful and beautiful in the plain, although the mountains that surround it are bare and rough. In the plain we saw many tall and thick cottonwoods and oaks; the watering place consists of an arroyo with a great deal of water which runs in a moderately wide valley, well grown with willows and cottonwood. We stopped on the bank of an arroyo, where we found a populous village in which the people lived without any cove, for they had no more than a light shelter fenced in like a corral. [Santa Clara River near Castac, Los Angeles County.] For this reason the soldiers called it Rancheria del Corral, and I called it Santa Rosa de Viterbo, that this saint might be protector for the conversion of these Indians. As soon as awe arrived they gave us many baskets of different kinds of seeds, and a sort of sweet preserve like little raisins, and another resembling honeycomb, very sweet and purging, and made of the dew which sticks to the reed grass. It is a very suitable place for a mission, with much good land, many palisades, two very large arroyos of water, and five large villages close together. Wednesday, August 9. This was a day of rest, in order to give an opportunity to the explorers to go and explore along the beach, for we had this high mountain range in sight, and we understood from the heathen that this is not the only one, but that in the direction that we are traveling there are four others, more rugged, and afterwards a large river which they say we cannot ford, and which runs to the sea; and that when we reach it we will have to turn back. All this day we had visits from these good Indians, who brought us their presents of pinole, nuts, and preserves. They begged us to remain with them, and I told them that we would return, with which they were delighted. One of the heathen who visited us here recognized Father Gomes and gave him an embrace, telling him by signs that he was a coast Indian, and that he had already seen him on the bark from the shore; he also recognized Senor Fages and Senor Costanso. This day we observed the latitude, and it was thirty four degrees and 47 minutes. The explorers came back in the afternoon with the report that the good road still continued through the valley, and that it was quite possible to go by way of the beach. This charming valley which begins after descending from the pass, I named Santa Clara. We found here a populous village, and the heathen wished to detain us, for they had prepared refreshments for us. We perceived that they were having a wedding, and they showed us the bride, who was the most dressed up among them all in the way she was painted and with her strings of beads. From here on the women begin to wear more decent clothing, for in the place of aprons they wear deerskins from the waist down, which serve as skirts, and little capes of rabbit skin to cover the rest of the body. From the diary of Costanso, the engineer, are the entries of the same dates.

Tuesday, August 8. We entered the mountain range, the road having already been marked out by the pioneers who had been sent ahead very early in the morning. Part of the way we traveled through a narrow canyon, and part over very high hills of barren soil, the ascent and descent of which were exceedingly difficult for the animals. We descended afterwards to a little valley where there was an Indian village. The inhabitants had sent us messengers to the Valle de Santa Catalina, and guides to show us the best trail and pass through the range. These poor fellows had prepared refreshments for our reception, as they saw that it was our intention to move on so as not to interrupt the day's march. They made the most earnest entreaties to induce us to visit their village, which was off the road. We had to comply with their requests so as not to disappoint them. We enjoyed their hospitality and bounty, which consisted of seeds, acorns and nuts. Furthermore, they furnished us guides to take us to the watering place about which they gave us information. We reached it quite late. The day's march was four leagues. The country from the village to the watering place is pleasing and picturesque on the plain, although the surrounding mountains are bare and rugged. On the plain we saw many groves of poplars and white oaks, which were very tall and large. The watering place consisted of a stream, containing much water, that flowed in a moderately wide canyon where there were many willows and poplars. Near the place in which we camped was a populous Indian village; the inhabitants lived without other protection than a light shelter of branches in the form of an enclosure; for this reason the soldiers gave to the whole place the name of the Rancheria del Corral. (To the Rancheria del Coral, 4 leagues. From San Diego, 58 leagues.) [Perkins notation: Tunnel Station.] Wednesday, August 9. Before our eyes extended vast mountain chains which we had necessarily to enter if we wished to continue our course to the north or northwest, as these were the directions most advantageous and most convenient for our journey. We feared that the more we penetrated into the country the greater the difficulties might be, and that we might be led very far from the coast. It was decided, therefore, to follow the canyon in which we had camped, and the course of the stream if possible, as far as the sea. To this purpose the scouts, who had been sent out early in the morning, had orders to proceed as far as they could, and to find out if there were any obstacles on the road. For this reason the people and animals rested today. A multitude of Indians came to the camp with presents of seeds, acorns and honeycomb formed on frames of cane. They were a very good-natured and affectionate people. They expressed themselves admirably by signs, and understood all that we said to them in the same manner. Thus they gave us to understand that the road inland was very mountainous and rough, while that along the coast was level and easy of access; that if we went through the interior of the country we would have to pass over five mountain ranges, and as many valleys, and that on descending the last range we would have to cross a full and rapid river that flowed between steep banks. During the night the scouts returned and reported that the land which led to the coast was level and contained plenty of water and pasture; they had not been able to see the ocean, although they had traveled for about six leagues following the course of the canyon. Portola, the comandante, the military man, with his mind on other matters, much more briefly tells his story of the entry to the Valley of the Little Santa Clara.

August 8th. We proceeded for 6 hours over one of the highest and steepest mountains and halted in a gully where there was much water and pasture. (Some natives appeared and begged us to go to their village which was near; there we found 8 villages together which must have numbered more than 300 inhabitants — with a great supply of grain. We rested for one day where there was a village of about 50 natives. For the benefit of those not acquainted with early California history, it may be wise to remind them that in 1769, or thereabouts, the California coast happened to be attracting international attention. Russia had commenced the establishment of trading posts for the rich fur trade starting in Alaska and gradually infiltrating down the coast as far as Fort Ross. England also had some claims to territory based on Drake's voyages searching for a northwest passage. Spain was already in possession of all Mexico and had long held lower California through the establishment of Jesuit missions. Spain's colonial policy made necessary and immediate settlement in California, if Spain's claims to California were to be generally recognized. Experience had proved to Spain the economy and success of allowing colonization to be carried on through the medium of the Catholic religious societies by encouraging them to establish missions for the propagation of the faith in heathen lands and gradually subjugating the areas around the mission by proselytizing. The Jesuit order happened to be unpopular with the Spanish government at this date, and the work was therefore turned over to the Franciscan order, to be carried out by missionaries and teachers from the Franciscan College of San Fernando at Mexico City. This plan was carried out under the leadership of California's first Franciscan presidente, Father Junipero Serra. Father Serra had come overland from Mexico City, and established headquarters at San Diego Bay which had been chosen as the site for the most southern of the prospective missions. Since 1594, Spanish maps had shown the Bay of Monterey, discovered on one of voyages of Vizcaino, and from its description and location it had been selected to be the site of the most northern mission, the plan being to establish future missions at about a day's march apart, each mission being a link in what was to be an unbroken chain of Spanish influence upon the coastal line. To find the Bay of Monterey, Fr. Serra had first sent his ships. The ships went as far north, possibly, as Drake's Bay, but failed to recognize the Bay of Monterey. Father Serra then determined to send an overland party, under command of his military commander, the governor of California, Gaspar de Portola. This party went down in history as the Sacred Expedition. (This Sacred Expedition also failed to recognize the Bay of Monterey but did find the Golden Gate — the Bay of Monterey later being found by a second overland expedition under Portola's leadership.) The entire proposition was simply one of adding Upper California to the territory under the Spanish flag in the cheapest possible manner. Nothing could be cheaper than allowing a handful of Franciscan friars, with a corporal's guard of Spanish soldiers, to subdue a tremendous territory by peacefully establishing a chain of missions. Had the friars been wiped out by hostile Indians, a thing that frequently happened, the Spanish crown suffered no loss. If the friars were successful, they would cheat the clutching claws of the Russian bear, already reaching down from the north to acquire more territory. This digression merely hits the high spots in explaining why the Sacred Expedition, or anyone else, for that matter, happened to come into the Little Santa Clara Valley at that particular date. Among the first group of white men to enter the Valley of the Little Santa Clara were such men as Rivera, comandante of California from 1773 to 1777; Fages, later to be not only comandante of California but also governor in 1782; Ortega, discoverer of the Golden Gate and founder of the Presidio of Santa Barbara; while the men in the ranks included Pedro Amador, Alvarado, Jose Raimundo Carrillo, Yorba de Cota, Oliveras and Soveranes, who later gave their names to many of the counties and most of the prominent Californian families. Father Crespi was the padre attached to the expedition. (It was a custom required of all Franciscan or Jesuit fathers proselytizing new countries to keep a daily diary.) Today those diaries are of major importance for historical source material. The naked Indians must have been highly startled to see the expedition climbing down the Indian trail from the south, especially if mules and horses were along, for those animals were not native to the valley. Neither was clothing, although the tribes down near Ventura wore garments of skins, but the Spaniards wore a sleeveless jacket made of several thicknesses of skins, which would turn arrows shot from a distance, and a divided leather apron fastened to the saddle covered the legs, practically a chaparejo, or chaps of today. (The friars wore cowled robes of coarse gray or brown material. The officers probably ran somewhat to colorful uniforms. The accompanying Indians were dressed as usual, i.e., undressed.) In the event of trouble, the soldiers were armed with lances, swords and a small carbine, and they carried bull hide shields on their left arm. Ortega's scouts went in advance, picking out camping places with water and feed. Theirs was peaceful work, as the party was already seven weeks out of San Diego. The record shows actual travel of only about three hours a day, covering about three leagues (approximately 2.6 miles to a league), resting one day in four, and normally they were proceeding on invitation and with guides from the tribal areas ahead, who had probably heard of the trade beads to be gotten by the superfluous food. On the night of August 7th, 1769, the Sacred Expedition camped about at Tunnel Station on the San Fernando Valley side of the mountains, and on August 8th, climbed down the old Indian trail, just about where Highway 99 cuts the crest of the mountains. At the hospitable request of Indians from the old village (about at Devendorf ranch), the expedition swung off the road to visit. The diary shows that Fr. Crespi named the valley August 9th, 1769, for Santa Clara, the founder of l'Ordre de Sainte-Claire, or Les Clarisses, in A.D. 1212, during the Dark Ages — the lady in question being described as a fashionable, frivolous girl who, when but 17, was so affected by the preaching of St. Francis that she became a nun at the convent of Porciuncula. Her day was August the 12th. The expedition camped by the Indian village of Chaguayabit and rested there August 9th, starting down the Little Santa Clara river banks toward the ocean August the 10th. For the next few years, the valley saw few white men, and its primitive life remained unchanged. Father Francisco Garces did come through here on his exploration of the Mojave Desert in April of 1776 and rested ten days. His diary reads as follows (Coues' "On the Trail of a Spanish Pioneer"):

April 13th. I passed over a sierra that comes off the Sierra Nevada and runs to the west-northwest, and entered into the Valle de Santa Clara, having gone two leagues on a north course, in the afternoon having gone a league and a half northwest, arrived at the Cienega de Santa Clara (Chaguayabit). One of the Jamajabs [Mohave Indians — ed.] having taken sick, I tarried in this place until the twenty-third day; during which I visited various rancherias that there are in these sierras, as also the canones and arroyos, with much water and abundant grass, and from whose inhabitants I experienced particular meekness and affability. I baptized one infirm old man, the father of the chief of the rancherias, having instructed him by means of Sevastian, though with difficulty. There came other Indians from the north-northeast, who promised to conduct me to their land, as also they did, with five more Jamajabs who arrived these days to trade. April 23 (1776). I departed west, and at a little distance took a course north, of which I surmounted the great sierra; and halted at a cienega that is on the descent, having traveled thus far nine leagues. The Franciscans had established missions at San Diego (1769), San Carlos-Monterey (1770), San Antonio (1771), San Gabriel (1771), San Luis Obispo (1772), San Juan Capistrano (1776) and San Buenaventura (1782). [The writer omits Mission Dolores-San Francisco, 1776, and Santa Clara, 1777 — Ed.] The jump from San Gabriel to San Buenaventura was 75 miles, altogether too long for a one-day march. Not only that, in the valley named by Fr. Crespi, Valle de Santa Catalina, but later to be known as the Encino (Oak) Valley, there were large numbers of Indian villages that could not possibly be converted and afterwards administered from these two missions. Father Serra died at San Carlos Mission in 1784, and his associate, Father Lasuen, had succeeded him as presidente of the California missions. Lasuen took up the torch of Serra and, as fast as California politics, as interpreted by the California civil governors, would permit, undertook the work of filling in the gaps in the chain of missions. In 1795, an expedition explored the valley north of San Gabriel for a mission site, to which was attached Fr. Vicente de Santa Maria. From Fr. Engelhardt's "San Fernando Rey" is taken the following excerpts of Fr. Santa Maria's report, sent from Mission San Buenaventura on Sept. 3, 1795.

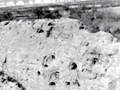

My most Venerable and Esteemed Fr. Presidente: In compliance with the resolution of the governor that an examination be made with the greatest exactitude and in a thoroughly satisfactory manner, in order to find the best place between this mission and that of San Gabriel, so that we may proceed with assurance in case the founding of another mission between this and that be conceded; and since his Honor wishes that a missionary make the survey, and your Reverence has entrusted this charge to me, I shall have to execute it perfectly. I have to report that on August 16th, at twelve o'clock at noon, I set out from this mission accompanied by Ensign Don Pablo Cota, Sergeant Don Jose Maria Ortega, and four soldiers.... On the nineteenth we left Calabasas at half past six in the morning, going on the Camino Real as far as Encino Valley, from where we took the direction toward the east-northwest [sic]. We went to explore the place where the alcalde of the pueblo (Los Angeles, Francisco Reyes, has his rancho. It lies in front of Encino [...] is distant from the Camino Real about two leagues.... We found the place quite suitable for a mission, because it has much water, much humid land, and also limestone. ... Stone for the foundations of buildings is nearby. There is pine timber in the direction of west-northwest of said locality, not very far away; also pastures are to be found and patches very suitable for cattle; but there is lack of firewood. ... To this locality belong, and they acknowledge it, the gentiles of other rancherias ... who have not affiliate with Mission San Gabriel.... On the twenty-fifth, we set out. ... After a league and a half, we found ourselves at a pass which was very rough, so that, in order to ascend and descend it, we had to alight. At a little distance from the descent we encountered a little ditch of water where we stopped at six in the evening. On the twenty-sixth we set out from there at six in the morning, and at eight we reached said place and came to a rancheria contiguous to a zanja of very copious water at the foot of [...] We followed this ditch to its beginning, which was about a league distant; and from here it is where the Rio de Santa Clara takes origin. The zanja is very easy of access, so that with its water some land can be irrigated; but in said district we found no place suitable for establishing a mission. It is six leagues distant from the Camino Real to the north and it has the additional drawback of the pass through the sierra. The first description of course is the site of Mission San Fernando, the second description is of the Little Santa Clara Valley headwater, which then, if ever, needed just one good modern Realtor to talk his way past the roughness of the mountain road, and assure the good padre of many wide boulevards for the future. [Perkins sold real estate — Ed.] As might be expected, without that aid, the San Fernando Valley, yet to be, won its first competitive struggle with the headwater area of the Little Santa Clara. San Fernando Mission was built in 1797. The mountain range to which Fr. Santa Maria objected remained in place with one major result, i.e., that the large gentile (unconverted) Indian population about the Chaguayabit and the headwater area were practically beyond the influence of the Mission San Fernando, and were still forty miles distant from Mission San Buenaventura, which meant that its local use was small. But another factor had to be considered. Under the Spanish colonization system, the missions contributed to the support of the presidios, where the military was maintained. The Santa Barbara Presidio depended in part upon the contributions of grain, hides, soap, tallow, etc., from San Fernando Mission. Also it was more than a day's trip from San Fernando mission to Mission San Buenaventura. Also in the Mission San Fernando grant were included the ranches of San Francisco Javier [Xavier], or Chaguayabit, and Camulos, both of which were on the same side of the range as Santa Barbara, with an easily traveled road running down the Canada de Santa Clara, and with ranches productive both for wheat and for cattle. They were, however, too far removed from the mission for efficient operation, and it was probably a mixture of the preceding reasons that inspired Father Dumetz, of San Fernando Mission, to build the first building in the Little Santa Clara Valley headwater area in 1804. This was an adobe structure (about 105 feet by 17 feet) for granary, dormitory and guest house use. The site was completely lost for half a century, and was finally rediscovered and identified in 1935 by R.F. Van Valkenburgh and the writer, who naturally found it while hunting for something entirely different. Archaeological excavation under Arthur Woodward of the L.A. County Museum showed a probable division into five[?] apartments, the living quarters being tile-floored and -roofed, walls built of typical mission adobe brick, whitewashed on the interior. The east end of the building was evidently the granary, and did not have a tiled floor. About 60 feet to the south of the structure is another wall line, probably the ramada wall, in the southeast corner of which was a kiln where the tile was probably baked, and adjoining which was another adobe store room. A plan of reconstruction, similar to that at Riverside, was shattered in 1936 when treasure hunters, the curse of all old missions, dug the tile floor out and practically wrecked the structure in a futile effort to find the treasure the archaeologists had located under the tile floors — evidently figuring that, as the diggers invariably stopped excavating when the tile floor was encountered, and always spread dirt over the tiles to discourage anyone from stealing them before leaving, there must have been mission gold hidden at the spot. The fallacy of this belief is quickly shown when it is realized that all California Indians were stone aged people, without use, possession or knowledge of metal, that the first gold discoveries were in 1842, and that the mission had been secularized in 1834, eight years before that date. [This statement should not be taken at face value — Ed.] The site of the building was on the projecting mesa, just across the creek entirely from Castaic Junction, a high elbow of ground, commanding an impressive panorama. Up to 1804, the valley had suffered little change. True, there was a slight infiltration of Mission Indians who were probably too far from the mission to be a serious menace to traditional customs. An occasional Spaniard undoubtedly came through the valley, but, taken as a whole, the picture was not greatly changed. Now it was different. Right at the site of Chaguayabit, the padres had established their local asistencia, to the Indians, a workshop. [Per mission records, the local estancia was not elevated to asistencia status — Ed.] As a matter of fact, even the Indian villages began to lose their original tribal associations and replace them with their mission affiliations. [That's because Spanish soldiers had removed all the local inhabitants to the San Fernando Mission by 1811 — Ed.] Now the villages in Placeritos and on the east side of the valley and in the canyons were known as Venturenos. [Perkins is incorrect. In his defense, at this writing, it was not widely understood that the local Tataviam people were of an entirely different ethnicity and linguistic group. Venturenos are Chumash peoples to the west. — Ed.] Chaguayabit itself however was Ventureno. [Ditto.] The medicine men could not face the padres, and it was probably then that the older men of the tribe sorrowfully bundled up their ceremonial regalia and packed it high into the precipitous cliffs of San Martinez Chiquito Canyon, in sight of the asistencia [sic], and piled the regalia into the storage cave, where the Pyle boys found it in 1884, sold the contents to a man named Bowers, then a Ventura editor, who in turn sold it to the Peabody Museum, where it is today. It must have been difficult for local Indians to follow the teachings of Franciscan fathers, when the Spanish soldiers, the only other white people they came in contact with, seemed to enthusiastically do everything the padres said was wrong. It would have been just as hard to understand why the mission and the lands which the padres kept saying belonged to the Indians, and for which the padres were only trustees, were only a source of work without recompense to the owners — if they were owners.

Download individual pages here. Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society collection.

|

Story: Rio Santa Clara in Costansó's Diary Perkins Manuscript: Colonization

Junípero Serra (1)

Junípero Serra (2)

Juan Crespí Story

Graves of Serra, Crespí, Lasuen

Serra's Coffin

Serra Cenotaph

Pedro Fages

Fages Marker

Francisco Garcés

Early Afro-Mexican Settlers (Video 2015)

Secularization & Sale, 1830s-40s (Engelhardt 1927)

Vischer 1865

Dedication 1925 x4

Bell at Camulos: Alaska Report 1923

Bell at Camulos (News reports 1923)

Bell at Camulos (Engelhardt 1927)

Pre-Restoration

Location 1928

Ruins

Roof Tiles x2

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.