|

|

SunCal Project Extends Development Up San Francisquito;

EIR Misidentifies Native American Burial Site.

By Leon Worden

SCVHistory.com | January 10, 2015.

|

Update 2018 — The development project never came to fruition. Instead, the city of Santa Clarita purchased the 176 acres of land from the developer for $1.55 million and preserved it as permanent open space.

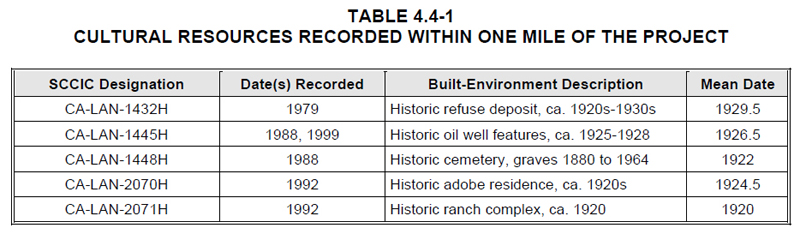

Approved by the county in 2008, a 37-home development project by SunCal Companies will adjoin the northeastern tip of the Tesoro del Valle community and push tract housing deeper into San Francisquito Canyon onto more of the ranch property homesteaded in 1916 by silent screen star Harry Carey. The project encroaches on several historical and cultural resources including a cemetery that the environmental documents misidentify as non-Native American. Project approval came just months before the U.S. economy went into a recession, and the developer put the project on hold. In 2012, as the economy began to rebound, the developer filed the final tract maps. In January 2015, the project was sent back to the Regional Planning Commission for a technical reconsideration because the developer's "will-serve" letter from the local municipal water agency was outdated. Under state law, development projects must be able to prove a water supply. The Newhall County Water District, which serves the neighboring 1,077-home Tesoro community, previously agreed to provide water for the new housing tract. The development project was initially proposed by Larwin Co. in 2000. During a series of public hearings and appeals from 2005 to 2008, the project was downsized from 60 single-family homes spanning San Francisquito Creek to 37 homes on 1- and 2-acre lots to the west of the creek, in order to avoid sensitive species in a county-designated Significant Ecological Area, and to maintain equestrian access through the rural canyon. Environmental impact reports (EIRs) are about more than flora and fauna and trails. One of many things an EIR must address is "cultural resources," which include paleontological resources (fossils), prehistoric resources (Native American sites dating prior to European contact, in our case 1769) and historic resources (modern, post-1769). An EIR must assess resources both within the project area and in surrounding areas that the project might "impact." The EIR for the SunCal project does this, but it contains errors and omissions. By way of background, the 185.8-acre project site abuts the Keatley property, which was once owned by the Perea and Ruiz families. The project's northern boundary is the current Lady Linda Lane; Lady Linda was Linda Perea (Packard). One omission from the EIR is the Butterfield Overland Mail Co. stage station known as Moore's or Hollandsville, which stood on the Perea property until it was wiped away by the St. Francis Dam floodwaters in March 1928. It isn't mentioned. Neither is the historic mine (which appears on government maps) known by some as the "Gold Bowl," immediately north of Lowridge Place, just east of the project site. It was worked in the 19th Century, shortly after (some say before) Francisco Lopez first discovered gold in Placerita Canyon in 1842, and it proved to be one of the Santa Clarita Valley's richest gold deposits. More importantly, the EIR misidentifies the Ruiz-Perea Cemetery (aka Ruiz Cemetery) as non-Native American; and the EIR makes no mention of the cemetery's association with the St. Francis Dam disaster, which was America's deadliest civil engineering failure of the 20th Century. Numerous St. Francis flood victims are buried there, including six members of the Ruiz family. Native American Interments The Ruiz-Perea Cemetery is located at the north end of the Keatley-Ponton property (see map above). While it may be the case that most cemetery occupants are of Mexican, Italian and other ancestry, several California Indians are interred there. Most notable among the Native American burials, from an SCV history perspective, are Fred and Frances Cook. Fred (1881-1958) and Frances (1884-1946) are buried together under a common gravestone. Fred and Frances are the patriarch and matriarch of modern-day Tataviam Indian families. As we have documented, Frances Cook (nee Garcia) was the hereditary chief of the local Tataviam families, having inherited the mantle from her father, Isodoro (b. 1860). Frances descends from individuals who, on her mother's side, lived at Chaguayabit (aka Tsawayung), a Tataviam Indian village at Castaic Junction, prior to European contact in 1769. Her ancestors' names are recorded in Spanish mission records. Fred Cook descends from California Indians of undermined origin, probably including Tongva. His paternal grandmother Trinidad Espinoza was born at the San Gabriel Mission, and his maternal grandmother, Florida Parker, is identified in mission records as a California Indian. The consultants who prepared the cultural resources section of the project EIR did not review mission records. In 2003, the consultants ordered a search of cultural resource records at the South Central Coastal Information Center at California State University, Fullerton. That is the accepted and appropriate "first step" in assessing cultural resources.

According to the EIR, "the records search provided information on known resources and on previous studies within one mile of the project boundaries." Those resources included the Harry Carey ranch house, the Harry Carey ranch complex, two historic oil well platforms, a historic dump — and the Ruiz-Perea Cemetery, which it identified as non-Native American. The consultants probably didn't expect to find evidence of Native American habitation or burial. According to the EIR, in 2000, the Native American Heritage Commission in Sacramento commented on the initial project documents. The consultants, BonTerra Consulting (now part of Psomas), subsequently "contacted the NAHC regarding the following: 1) special Native American sites or properties that may be present in or near the project area; and 2) a list of local Native Americans who could be contacted about the project." The result? "The NAHC search of the Sacred Lands File did not reveal any Native American sites or properties in the vicinity of (the project area). No further Native American consultation was undertaken because no prehistoric sites were identified in the project area." The phrase, "no prehistoric sites," is a misnomer. According to NAHC, "Prehistoric sites represent the material remains of Native American societies and their activities. Ethnohistoric sites are defined as Native American settlements occupied after the arrival of European settlers in California." Both types of sites (as well as historic buildings) must be assessed. The Ruiz-Perea Cemetery is an ethnohistoric Native American site. Under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), sites must be assessed if they are eligible for listing in the California Register, which is "an authoritative guide to the state's historical resources and to which properties are considered significant." According to the California Office of Historic Preservation (OHP), "Unless a resource listed in a survey has been demolished, lost substantial integrity, or there is a preponderance of evidence indicating that it is otherwise not eligible for listing, a lead agency should consider the resource to be potentially eligible for the California Register." The Ruiz-Perea Cemetery is a listed site (as CA-LAN-1448H), but it is not listed as containing Native American burials or as a site that is significant to a Native American community. According to OHP, "a resource does not need to have been identified previously either through listing or survey to be considered significant under CEQA." Thus, the fact that it wasn't recognized as a significant Native American site when the EIR was written has no bearing on its significance today. Heightened Significance CEQA establishes the processes for dealing with sites that meet the definintion of "unique archaeological resource" under Public Resource Code Section 21083.2. PRC Setion 21083.2 defines "unique archaeological resource" as "an archaeological artifact, object, or site about which it can be clearly demonstrated that, without merely adding to the current body of knowledge, there is a high probability that it meets any of the following criteria: (1) Contains information needed to answer important scientific research questions and that there is a demonstrable public interest in that information; (2) Has a special and particular quality such as being the oldest of its type or the best available example of its type; (3) Is directly associated with a scientifically recognized important prehistoric or historic event or person." The descendants of Fred and Frances Cook have repeatedly demonstrated a "public interest" in the Ruiz-Perea Cemetery, as evidenced for example in a March 2001 reunion of Fred and Frances' descendants at the cemetery site. The cemetery actually meets the criterion of being "directly associated with a scientifically recognized important prehistoric or historic event or person" in more than one way. The association with an "important person" is seen in the fact that Frances Cook was chief of the local Tataviam families and moreover that she is one of very few people whose connection to Native Americans at Castaic Junction prior to European contact is recorded. That connection is "scientifically" important, as well. In March 2005, a match of mitochondrial DNA was made between a prehistoric burial site in Palmdale and samples taken from Lydia (aka Lyda) Manriquez and other family members. As of 2015, it is the ONLY instance in which a prehistoric Native American site in California has been scientifically linked to living Native Americans. Lydia Manriquez was a daughter of Fred and Frances Cook. Fred and Frances were also the grandparents of the late Chief Charlie Cooke and great-grandparents to the current chief, Ted Garcia Jr. In addition to its Native American occupancy, the Ruiz-Perea Cemetery "has a special and particular quality," as enumerated in PRC Setion 21083.2, and "is directly associated with a scientifically recognized important prehistoric or historic event": It is the nearest and most closely associated burial site for St. Francis Dam victims. The SunCal project's EIR is silent on the signifance of the Ruiz-Perea Cemtery in the context of the St. Francis Dam — or any other context. So What? Why didn't the Ruiz-Perea Cemetery appear in the California Register as a significant Native American site when the EIR was written? And why did the EIR consultants misidentify it? Possibly because both the DNA analysis was performed, and the genealogical research was conducted, after 2000/2003. NAHC might not have known, and the consultants looked no further. No such explanation can be given for the failure to associate the cemetery with the St. Francis Dam. The reader might wonder: If the Ruiz-Perea Cemetery isn't going to be destroyed by the SunCal project, and if it isn't even on the SunCal property, why does it matter if the SunCal EIR doesn't identify it as a Native American site? It matters because the EIR is a government-certified document that says there are no "Native American sites or properties in the vicinity." It is an official "record" that will be discovered in a "records search" one day, when a future owner of the Keatley property decides to develop it. It is not too late. With the project going back to the Regional Planning Commission to resolve water issues, the county could require the developer to consult with descendants of Fred and Frances Cook and prepare an addendum or supplement to the EIR, correcting the errors and omissions. For the record.

|

Enrique (Henry) & Rosaria Ruiz

Ruiz Family x7

Perea (Founder)

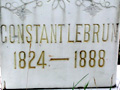

Constant LeBrun

Gus LeBrun Marker & Death Certificate

Nick Rivera

Leonardo Cesena

Erratchuo 1928

1928 Mourners

Newhall Cowboys 1928 Marker x2

Johnny Cordova

1963 Mabel Packard Wagner Visit x5

Fred & Frances Cooke

Harry S. Chacanaca

Pre-2002 Fire

2002 Copper Fire x10

Raw Video ~2004

Tesoro Extension 2015

City Open Space 2018

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.