|

David Wark Griffith brought a not-quite-18-year-old Mary Pickford and the rest of his traveling Biograph cast and crew to Rancho Camulos and the town of Piru in the spring of 1910. Mission: Adapt Helen Hunt Jackson's still-popular 1884 novel, "Ramona," to the still-new medium of film. It is the first moving picture known to have been made in the Santa Clarita Valley (or, as it's known in Ventura County, the Santa Clara River Valley).

Screenshot: Mary Pickford as Ramona and Francis J. Grandon as Felipe converse in the courtyard of the Del Valle family's 1853 adobe home at Rancho Camulos. Click to enlarge.

|

Griffith had begun directing for the Biograph Company in New York in 1908. His arrival in California in January 1910 made Biograph the third major film company to set up shop out West, following Selig and the New York Motion Picture Company [Bowser 1990:152]. California was the place everyone wanted to be; Florida and Texas could compete for year-round filming conditions, but California offered unmatched variety: "summer greenery and winter snow, sunny beaches, barren deserts and rocky mountains ... all within a short distance of each other" [ibid:151].

Filming "Ramona" at the fabled "Home of Ramona" (Rancho Camulos) not only provided authenticity that was marketable — "Ramona" was probably the first moving picture to credit its filming location on screen — but it also freed the company from the stage, fostering innovation. "Ramona" was the first film — at least the first film by Griffith, and likely overall — to use very long shots [Barry 1940:17], which it did with both the action and the mountainous topography. "The confines of the stage, so oppressive in earlier films, were being broken, movement in any direction on the screen was employed freely and the motion picture began finally to be a fluid, eloquent and utterly novel form of expression" [ibid.]. The combination of D.W. Griffith and pioneering cinematographer G.W. "Billy" Bitzer, who was present for the beginning of the industry in the 1890s, also invented the closeup and the fade in/out.

Despite its 17-minute runtime, "Ramona" was a one-reeler. How can a single 1,000-foot reel of film run longer than 11 minutes, you ask?

Well, in the 1910s, silent movies were shot at 16 frames per second (fps), and 1,000 feet of film could hold 16 or 17 minutes of action at that speed.

Frame rates increased to 24 fps when talkies came in, so more film stock was required to capture the same amount of action. At 24 fps,

11 minutes of action would fill a 1,000-foot reel. With 11 minutes of action captured at only 16 fps — imagine cranking your camera slower —

you'd have one-third of a film reel left over. Had "Ramona" been shot at 24 fps, two reels would have been required for its 17 minutes of action.

|

In the spring of 1910, Griffith had a Biograph contract that paid him on both the production and the distribution side. The real money was in distribution. He cleared $50 a week plus one-tenth of 1 percent per lineal foot of positive film sold [ibid.:13]. His "Ramona" was 1,000 feet, had multiple U.S. releases, and was sold to theaters around the world.

It was one of hundreds. Through 1913, Griffith was churning out one 6-minute and one 12-minute subject every seven days for Biograph. So, at 17 minutes, "Ramona" was a bit of an exception in terms of length. Bitzer remembered it as "one of the longest pictures we made" [Bitzer 1973:81].

Entertainment being "soft" news at the time, Biograph and other film companies were able to control their own publicity. They sent synopses of their productions (including spoilers!) to newspapers and magazines, which usually printed them verbatim, sans byline. Thus, substantially similar copy appears universally, as shown below.

The informed reader will note that Biograph's publicity hounds overstated the connection between the "Ramona" story and the Del Valle family of Rancho Camulos — which was typical of the period. The connection was rooted in the popular culture.

Vacationers consistently made Rancho Camulos a must-see destination in hopes of encountering the "real Ramona." But there was no such person. The characters in the story are fictional. They are amalgamations of people Jackson met and heard about during her California travels. True, there really was a Del Valle family matriarch who died in 1905, but saying "the Señora (of the story) has died," which the promoters did in 1910, is a misappellation.

Jackson visited Rancho Camulos one afternoon in 1882 but drew most of her knowledge of its people and its functions from discussions with friends in Los Angeles.

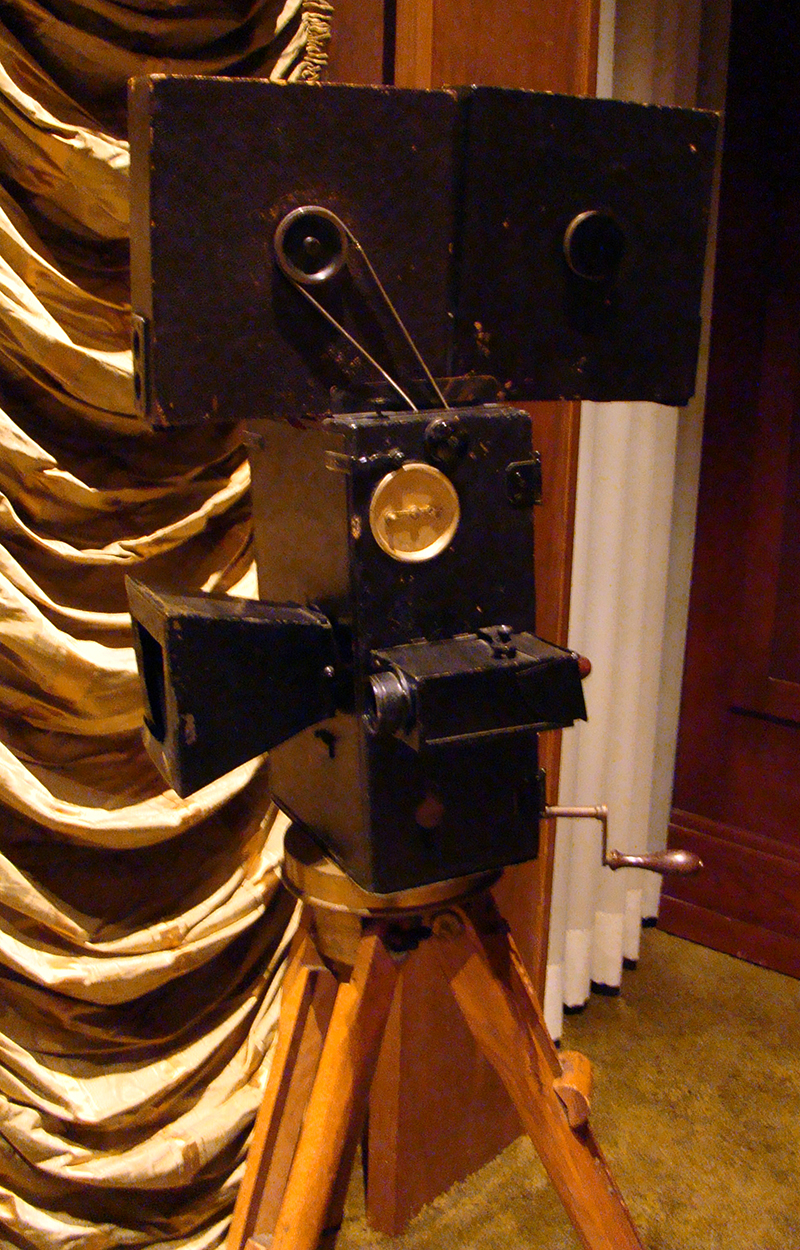

A camera used by Billy Bitzer in 1912. In the Nethercutt Collection at San Sylmar. Click for more.

|

José Jesús López, who was Edward F. Beale's ranch foreman at Tejon, was one of many claimants to a piece of the story. He said Jackson "talked with me about the plot for her story and about the characters to use in it." He said he told Jackson about a "half-blood Indian girl who was born at the old Castaic headquarters of Rancho San Francisquito" and who "had a rather tragic life;" and about her husband, a man named Alejandro who, like the Alessandro of Jackson's novel, "headed a band of Indian sheep shearers."

Jackson also visited Riverside and San Diego counties. If she did talk to José Jesús López, perhaps she liked the name Alejandro and affixed it (or an Italianization of it) to the story of Juan Diego, a Native American sheep shearer in San Jacinto who "borrowed" the wrong horse in 1883 and was murdered for it by Sam Temple, who was exonerated. Under California law at the time, a white man could not be convicted on the testimony of an Indian. Helen Hunt Jackson knew the story and may well have met Juan Diego's wife, Ramona Lubo, a master Cahuilla Indian basket weaver who later insisted she was the "real Ramona" of the story.

Griffith found a way to tell the "Ramona" story in 17 minutes, but the stories about the story go on.

|

Click to enlarge.

|

Home of Ramona in Moving Pictures.

Enterprising Theater People Have Forty Actors Represent Scenes of the Story at Camulos.

The Daily Oxnard Courier | Thursday, April 7, 1910.

Few people realize the expense connected with the taking of the films for moving pictures; and still fewer have any idea of the carefulness with which these films are prepared. Our people had the opportunity last week to see and know for themselves. The American Biograph Co. of New York sent about forty well-known theater people to Piru and on Wednesday [May 30, 1910], they commenced the taking of pictures for a moving picture representation of Helen Hunt Jackson's well-known book, "Ramona." They were very courteous and pleasant, willing to answer questions, and did not seem to care if people "rubbered" while they were at work.

The conditions at Camulos are very much the same as when the gifted author wrote her story. The weather was auspicious, the air languorous, restful and quiet. The orange trees were laden with luscious fruit, and the rich perfume of the orange blossoms made one almost feel that he and other flowers in profusion and the graceful foliage of the ornamental trees added to the incense from nature's censer and the chirp and anthem of birds and drone of bees and insects combined to turn back the dial of progress and Ramona, Felipe, Sonora, Indiana were what we expected to see; anything else would have seemed out of place.

The manager of the company and his helpers made careful inquiries and as much as they could shut the door of the world and lived in the orange trees, camped in the canyons, threaded tortuous mountain trails and fled and suffered with Ramona and Alessandro. The actors for each part had been carefully selected so that in temperament and inclination they seem ed to fit into and live the life of the early days.

The principal scenes were enacted in the actual places where the author pictured them so these films will be as real a representation as can be made of the characters and the places mentioned in "Ramona." The old chapel with its shell front, beautiful rich altar and quaint furniture for the outer court; the sheep shearing, the household arrangement, the flight, all are true to the old days.

The company look wonderful pains and spared no effort to secure accurate pictures. An Indian village was built and burned; they climbed mountains with the fearlessness of Alpine guides, and as many of the actors have a national reputation, the pictures should be among the best.

— Free Press.

|

Click to enlarge.

|

Varsity Theater to Show Ramona.

Berkeley Daily Gazette | Wednesday Evening, May 25, 1910.

The Varsity theater management has concluded arrangements for the appearance tomorrow of the highly interesting motion picture, of the Biograph company, entitled "Ramona." It is a story picture of the white man's injustice to the Indian and is taken from the novel "Ramona" written by Helen Jackson.

Intensely thrilling without sensationalism, it most graphically illustrates the white man's injustice to the Indian. It is a romance with a deep motive, told with such sympathetic tenderness that the reader longs to visit the scenes wherein lived the simple, patient Ramona and the noble-hearted Alessandro, as described by Mrs. Jackson.

Realizing what a gratification, both re-creative and instructive, the depicting of this favorite novel, with absolute authenticity, would be to the patron of motion pictures, the Biograph company made the journey to Camulos, Ventura county, California, where were found the identical locations and buildings wherein Mrs. Jackson placed her characters.

The house wherein Ramona lived with its vine-clad verandas; the inner-court, which is a veritable paradise, the little chapel amid the trees, the huge cross, and the bells from old Spain are all apparently just as Mrs. Jackson saw them, and while the very air breathes romance there is a pious solemnity about the place that is awe-inspiring.

The production adheres closely to the novel, showing the experiences of Ramona, the little orphan of the great Spanish household of Moreno, and Alessandro, the Indian. It opens with his arrival at the Camulos ranch with his sheep-shearers, showing his first meeting with Ramona. There is at once a feeling of interest noticeable between them which ripens into love.

This Senora Moreno, her foster mother, endeavors to crush, with poor success, until she forces a separation by exiling Alessandro from the ranch. He goes back to his native village to find the white men devastating the place and scattering his people.

The Senora, meanwhile, has told Ramona that she herself has Indian blood, which induces her to renounce her present world and go to Alessandro. They are married and he finds still a little shelter left from the wreckage. Here they live until the whites again appear and drive them out, claiming the laud.

From place to place they journey, only to be driven further until finally death comes to Alessandro just as aid comes in the person of Felipe, the Senora's son, who takes Ramona back to Camulos.

|

"Ramona" Motion Pictures Tonight at Victory Theatre.

The Daily Oxnard Courier | Friday, July 8, 1910.

Click to enlarge.

|

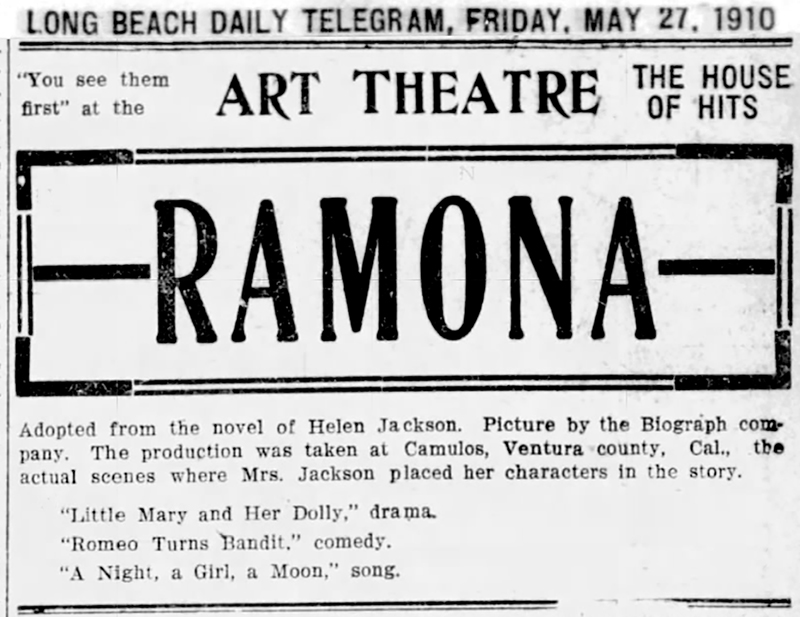

"Ramona," a story of the white man's injustice to the Indian, will be given at the Victory Theater tonight. The pictures are produced by the Biograph company. They are adapted from the novel of Helen Hunt Jackson. The production was taken at Camulos in this county, the actual scenes where Mrs. Jackson placed her characters in the story.

There are few American novels better known than the story of "Ramona" by Helen Hunt Jackson. Intensely thrilling without sensationalism, it most graphically illustrates the white man's injustice to the Indian. It is a romance with a deep motive, told with such sympathetic tenderness that the reader longs to visit the scenes wherein lived the simple patient Ramona and the noble-hearted Alessandro, as described by Mrs. Jackson.

Realizing what a gratification, both recreative and instructive, the depicting of this favorite novel with absolute authenticity would be to the patron of motion pictures, the Biograph company made the journey to Camulos, Ventura county, California, where were found the identical location and buildings wherein Mis. Jackson placed her characters. The house in which Ramona lived, with its vine-clad verandas, the inntercourt, the little chapel amid the trees, the huge cross, and the bells from old Spain are all apparently just as Mrs. Jackson saw them, and while the very air breathes romance there is a pious solemnity about then place that is awe inspiring.

Ramona, the little orphan of the great Spanish household of Moreno, knew nothing of her own ancestry. She had id lived at the Camulos ranch ever since she could remember, Senora Moreno being the only mother she bad ever known. She did not know who her parents were, whether they were living or dead, or why she lived in the Senora's house as her daughter, attended equally with Felipe, her son. Since the death of General Moreno, young Filipe had conducted the affairs of the ranch, and adhered to his father's custom of employing each season a band of Indian sheep-shearers from Temecula, of which Alessandro was the leader. Alessandro was a rather superior type of Indian, the son of Chief Pablo, who had been the leader of the choir at the San Luis Rey Mission. Alessandro, inheriting his father's love for music, sang and played, was possessed of a fair education, and of well-grounded religious principles.

The sheep-shearing at Moreno's was always undertaken upon the arrival of Father Salvierderra, the dear old padre who trudged through Southern California from ranch to ranch, year after year, that the faithful might he afforded an opportunity to hear mass and receive the word of God at least once a year. It is in the evening of the day of the padre's arrival, that Alessandro appears with his band of shearers. Ramona is seated on a bench in the grove, mending a rent in the altar-cloth to be used in the chapel next morning. At sight of the beautiful girl, Alessandro halts for a moment transfixed with admiration. He experiences an indefinable tenderness for the unknown maiden, he having never seen her before, as she had been at school in the Convent of the Sacred Heart at Los Angeles, during his previous visits to Camulos. They meet at the chapel the next morning and, although each fights against it, there is an irrepressible interest in each other growing within them. So compelling does it become that Ramona is moved to reject the suit of Senor Felipe. At length Ramona, realizing her own helplessness and the grief that she is causing Alessandro, listens to the prompting of her heart and confesses her love to him. It is now that the Senora Moreno appears and separates them, giving Ramona a blow in the face, so far does her temper impel her. Locking Ramona in her room, the Senora exiles Alessandro from the place. The poor fellow makes his way back to Temecula, his native village, to find that the whites have devastated it and scattered his people, his father being among the dead. Crushed in spirit and heartbroken, he wanders back to take one last view of Camulos and her whom he feels is now far beyond his reach. But he does not know that Ramona has discovered that she is nearer to him than ever, for she has learned that she too has Indian blood. The Senora, rather through spite than anything else, has told her that her father was the fiance of Senora's sister, who after a misunderstanding between them had, through pique, married an Indian maiden. Ramona was their child, who at the death of her parents, while still an infant, was left at the Moreno household.

This intelligence is most agreeable to her, as it refutes Senora's assertion that a marriage with the Indian Alessandro would be ignoble. Her natural intuition tells her of Alessandro's return and so she goes to meet him, and despite candid exposition of his now penniless condition, she declares she is determined to leave her world and go with him. Making their way to San Diego, they are married by Father Gaspara. Returning to his former heath, he finds a little shelter left from the wreckage, a small adobe hut, where the young couple make their home for about two years, during which time a child blesses their union. However, their happiness is cut short by the appearance of the whites, who drive them out, claiming the land as theirs. Homeless again, they wander forth, and during their journey from place to place they suffer the loss of their baby, who really dies of hunger. They bury it and then wander on. By this time poor Alessandro's mind becomes shattered by grief. Finally they locate at the very summit of the mountains, feeling that they are now free from molestation, but even here they are besieged by the whites and ordered to move on. Alessandro pleads with them to be merciful, but in answer he is cruelly shot down in the presence of the horrified Ramona.

During all this time many changes have transpired at Camulos. The Senora has died, and after her death Felipe starts out to find Alessandro and Ramona, and after a long journey comes upon Ramona as she kneels beside the pyre of her dear husband.

|

Click image to enlarge.

Click image to enlarge.

|

|