|

|

Part 1: The Route Over the Ridge.

By Alan Pollack, M.D.

| Heritage Junction Dispatch, May-June 2015.

|

But the initial proposal for the Ridge Route was not without controversy. Proposed State Highway to Bakersfield On Nov. 3, 1912, the Los Angeles Times reported on "the proposed state highway direct to Bakersfield." The final hearing on the proposed road was to be held later that month by the state Highway Commission. The article stated: "When completed, which will probably be in about a year, the state highway from here to Bakersfield will be unique and admirable among mountain roads of the country." A competing proposal would take the road through Soledad Canyon, out to Lancaster and Mojave, and then through the Tehachapi Pass into the San Joaquin Valley and on to Bakersfield. This route would essentially follow the Southern Pacific Railroad line. But the Ridge Route was favored over the Tehachapi Route by the state Highway Commission and the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce since it would save 50 to 60 miles of driving and avoid shifting sands and creek crossings. The Times article pointed out further: "Notwithstanding the wild nature of the country, the highway will be as level as a city street. The maximum grade will be only 6 percent, and in few places will it be necessary to establish a grade as high as that. It will be possible for the automobile driver to go from here to Bakersfield on the high gear over a paved road with the friction reduced to a minimum — all the advantages of a mountain ride without any of its discomforts." As things were to turn out, this statement about the comforts of the road would prove to be overly optimistic. The proposed road would be 21 feet wide in the cuts, 24 feet wide at the fills, and would be paved to a width of 15 feet throughout. In reality, the road was not completed until 1915, and it wasn't paved until 1919. Competition from Tehachapi At the time of the proposal, there were many cities and localities requesting and demanding that the new road be routed through them, but meeting all of these demands would have added many miles to the route and greatly increased the cost. The commission thus chose to follow the edict of the Highway Act of 1909, "to build by the most direct and practicable route, depending upon its tributary roads from each side to complete the highway connection." The Tehachapi Route was said to impose a "tax" of $5 on every automobile, since it was estimated that the cost of driving would be about 10 cents per extra mile. Ultimately and as expected, the commission chose the Ridge Route over the Tehachapi Route. But there were those along the Tehachapi route who attempted to reverse the decision of the commission.

In favor of the Ridge Route, they further stated that the Tehachapi route would be 57 miles longer than the Ridge Route; that the extent of mountain grade on the Tehachapi would be double the 6 percent grade of the Ridge Route; and that unlike the Ridge Route, the Tehachapi route would be subjected to the excessive summer temperatures and high winds of the Mojave Desert. Also mentioned were bad drainage conditions and multiple stream crossings along the Tehachapi route, the increased maintenance cost of the Tehachapi due to its location in canyons as opposed to mountain ridges, and the increased cost of $500,000 more to build the Tehachapi as opposed to the Ridge Route. Later in April, the Motor Truck Club of California also followed the lead of the Auto Club and passed a series of resolutions favoring the Ridge Route over the Tehachapi route. By June 2013, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors had come up with a "compromise route" which would add an additional 30 miles to the proposed Ridge Route. The compromise road would go through Mint or Bouquet Canyon to the Antelope Valley and then proceed to the Tejon Pass and on to Bakersfield. The Auto Club vigorously opposed this plan, stating, "it will cost a quarter of a million dollars more to build the longer route and will impose the additional run of thirty miles upon every automobilist making the trip." Great Ridge Route Soon to be Passable

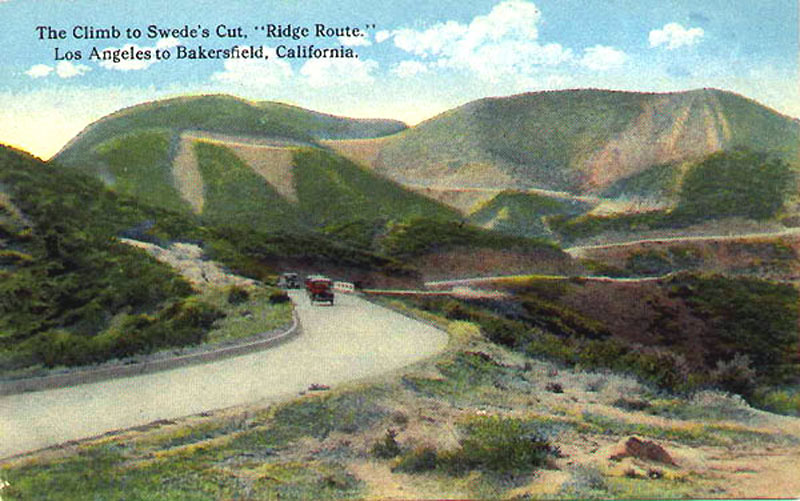

The new route was to cut the travel time between Los Angeles and Bakersfield from well over six hours to just four hours. It was also destined to be a new tourist attraction, climbing for 30 miles "through some of the most wild and rugged mountain country to be found in Southern California." The road was due to be opened to travel within about 45 days of the last grading, as the Highway Commission planned to oil the road to preserve the surface. It was not to be paved for at least two years "owing to the great number of fills that must be allowed to thoroughly settle." N.D. Darlington of the State Highway Commission proudly told a Times reporter: "For the most part our work of highway building has been merely to improve existing roads. In the Ridge Route, however, we had an opportunity to so vastly improve one of the main trunk line roads between two important points that I regard it as the most striking single piece of work that we have been able to accomplish." On Sept. 9, 1915, Darlington led the first trek of automobiles over the Ridge Route, consisting of members of the Board of Supervisors and representatives of the Chamber of Commerce and Auto Club. Carl McStay of the Auto Club noted "a saving of twenty-four miles. That means a saving of from $1 to $3.50 in gasoline and maintenance for every automobilist that goes over this road from now until eternity." Describing the new road, the newspaper reported: "It is the Ridge route in fact, for the road leaps from ridge to ridge over connecting causeways. It is a highway hung up against the sky, with the dark canyon of Castaic Creek yawning at one turn, and a smiling ensemble of chaparral-clad and creased hills at another. ... It is a road that traverses a new country of great possibilities, runs close by historic Fort Tejon, and finally merges in the mountains with the concrete road system of Kern County." Ridge Route Opens

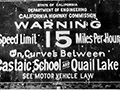

The Times advised motorists: "To reach the beginning of the ridge route, motor cars will travel out through the San Fernando Valley over the San Fernando boulevard, passing through the fertile fields at the base of the foothills, and on to Saugus, where the turn is made into the Castaic country." On Nov. 16, 1915, the Los Angeles Times reported from Bakersfield: "The 'Ridge Route' on the state highway between this city and Los Angeles was formally opened for traffic today, reducing the distance between here and the southern metropolis to 126 miles. ... Travelers are requested to keep to the side at the present time as there is some oil on the highway, which is best left unmolested." It was noted that the Auto Club had placed direction and warning signs along the new highway in world-record time. What should have taken two weeks was accomplished in one evening. Each sign was made of metal, affixed to a metal post that was sunk three feet into the ground. The Auto Club had been given only 24 hours' notice by the Highway Commission to get the job done before the road was to open. The majority of the signs were to warn motorists to keep to the right side of the roadway and to sound horns at all curves. At the two summits and ends of the road, large signs read: "Caution! 29 Miles Mountain Road. Grades. Curves. Drive Slowly — Keep Right. Sound Your Horn!" Today, the old Ridge Route still hugs the ridges of the San Gabriel and Tehachapi Mountains as it did back in 1915. It has been closed to vehicular traffic for several years by the U.S. Forest Service due to extensive damage from heavy rains during the last El Nino weather event. In the valleys below runs the modern Interstate 5, which now serves as the main artery between northern and Southern California, much as the Ridge Route did in its heyday. And time marches on. Alan Pollack, M.D., is president of the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society.

|

SEE ALSO:

Ridge Route Series

Story by Harrison Scott 2004

Auto on Ridge Route ~Late 1910s

1918-1930

1920s

Castaic Area ~1920s

Serpentine Drive x2

Ridge Route ~1930s

Grapevine Grade (Mult.)

Speed Warning 1920s

Graceful Turns ~1930s

4-26-1937

Film: Gorman to Grapveine, Winter 1939

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.

Historian Harrison Scott called it "the road that united California." The famous Ridge Route was the first road to serve as a direct connection between the Santa Clarita and San Joaquin valleys. It was thought that California was in jeopardy of being divided into two states due to the difficulty in navigating the mountains north of Santa Clarita prior to the construction of the Ridge Route.

Historian Harrison Scott called it "the road that united California." The famous Ridge Route was the first road to serve as a direct connection between the Santa Clarita and San Joaquin valleys. It was thought that California was in jeopardy of being divided into two states due to the difficulty in navigating the mountains north of Santa Clarita prior to the construction of the Ridge Route.