|

|

Part 2: Ridge Route Paves the Way.

By Alan Pollack, M.D.

| Heritage Junction Dispatch, July-August 2015.

|

However, much work was left to be done to ease the passage of automobiles over the new route. In fact, the road was not paved until a few years later. Before the Ridge Route Twelve years prior to the opening of the highway, a civil engineer for the Edison Co. ran a survey over the mountains for a pole line that would later parallel the road. In 1916, he described to the Los Angeles Times his experience traversing the mountainous area that preceded the Ridge Route: What was originally an Indian trail had become a poorly maintained cattle trail which represented the only way for drovers to get their stock out to the railroad shipping lines running through the San Joaquin Valley. The first vehicles to use the route were wagons belonging to the Edison Co. The ruts from these wagons became used as some semblance of a road that eventually became the Ridge Route. The route across the ridge presented many unforeseen difficulties for the surveyor and his crew. Water was so scarce that the crew could not wash its hands or faces for three weeks in order to save what little water they had for their horses. Houses of any kind were few and far between. They underestimated how much time it would take to extend the power line over the route and almost ran out of supplies. A job that was supposed to take three days lasted more than twice as long. On a subsequent trip over the route, the surveyor was accompanied on horseback by several of the directors of the Edison Co. He later stated: "What these men had to say about the 'Ridge Route' of those days was interesting, but I do not believe it would be printable."

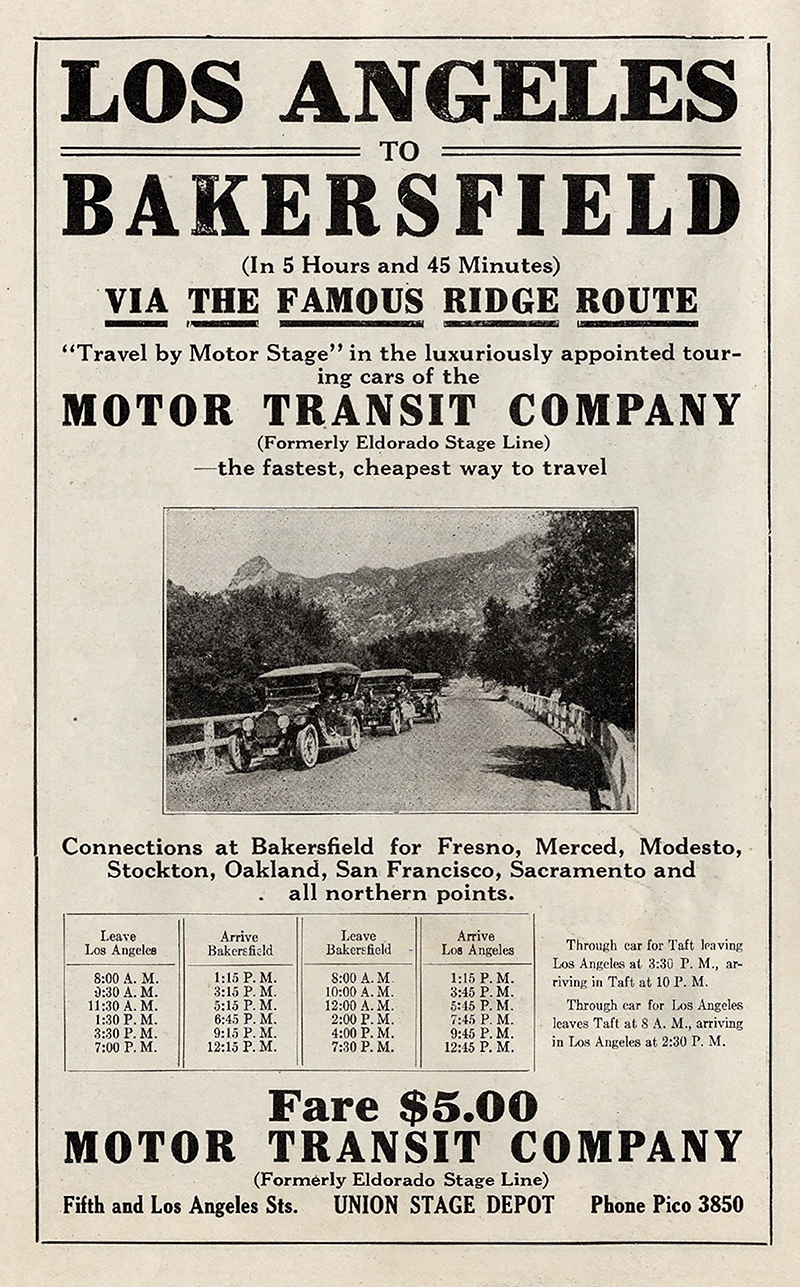

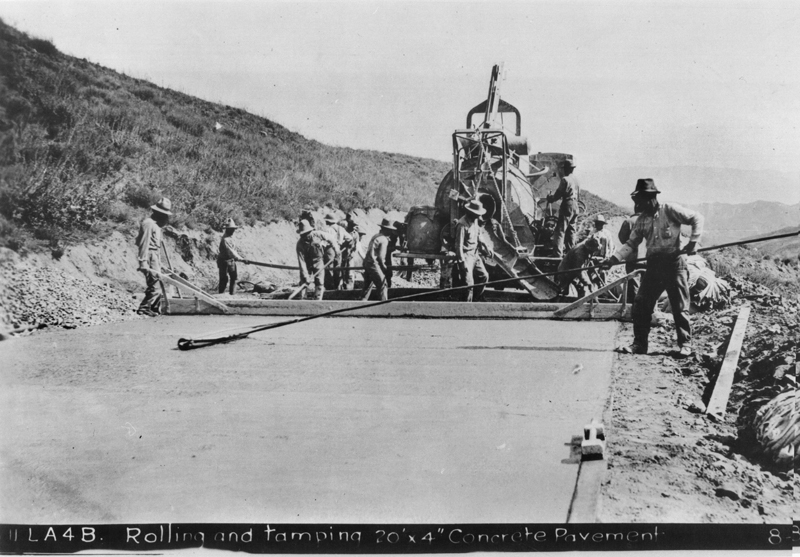

Route Opens After the road opened in 1915, the advantages of the new highway were seen almost immediately. Even over the unpaved road, auto stage (bus) lines loaded with up to nine passengers and their luggage could beat the Southern Pacific rail line running between Los Angeles and Bakersfield. Four large Packard cars carried passengers daily between the two cities. Without exceeding the speed limit, the auto stages could make it to Bakersfield in six hours, inclusive of a half-hour stop for lunch. In contrast, the Southern Pacific's Owl train took 6-1/2 hours to connect the two cities at a much higher fare for its passengers. By 1917, as reported in the L.A. Times, the Ridge Route had become "the best known highway in the entire West." It was popular with tourists as a scenic route that was comparatively safe. An endless chain of trucks plied the route night and day, carrying the resources of the San Joaquin Valley to the markets and trading points of Los Angeles. Farm machinery, mining machinery and equipment for the oil well districts were transported over the road by truck from the railroad stations. Scores of buses traveled the route carrying passengers between San Francisco, Fresno, Bakersfield and Los Angeles daily. Paving Starts Paving of the Ridge Route began by 1918. Due to the paving project, there were initially two steep but navigable detours at either end of the road. A 4-mile detour began from the schoolhouse at Castaic Station and went up a narrow canyon before climbing steeply up the side of a hill and back to the main highway. A detour at the north end of the road was less steep but had sand in places that required autos to use their low gear. Both detours were narrow, with few passing places for autos. At one point on the south end, the detour passed through a ranch at which point it became so pinched that there was not enough room for two cars to pass between two lines of barbed-wire fence on either side of the road. The road between the two detours was rougher than it had ever been since opening. There were many dirt and rock slides that were not repaired except for maintaining a pathway just wide enough for a car to pass through. On July 7, 1918, the Times reported that the detour at the south end of the road had been eliminated by the opening of five miles of paved road. It estimated that by July 20, the new pavement between Sandberg's and Crane Lake would be hard enough to uncover and open for traffic. In December 1918, a new stretch of pavement opened at the north end of the road near Sandberg's. Construction of the Sandberg link was hampered by lack of materials, labor and water. After completion of the Sandberg link, construction was halted for the winter, with plans to resume in the spring.

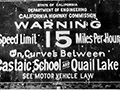

Cadillac agent Don Lee found out the answer from the office of the Highway Commission and told the L.A. Times: "Less than 18 miles of the Ridge remains to be paved, and I am informed that this will be completed during the summer and the Ridge will be a paved road from end to end before next winter. Over 12 miles of paving has been laid during the last year, and work is now in progress. The remaining road has been graded and is ready for paving. Within a very short time, all travel even to a wheelbarrow will be stopped. This is necessary on account of the conditions in the higher parts of the Ridge. The Ridge Route has been in poor shape for over one year, and the paving of this road will remove one of the unpleasant features of the trip between Los Angeles and San Francisco... "On account of the many turns, a couple of good features are being incorporated in the work now being done. On the blind curves, daylight cuts, or benching, is being put in. This consists of cutting away enough of the hill on the blind side to permit a view of the vehicles that might be coming around. ... On the dangerous curves, curbing is being put in. This curbing is 6 inches wide and 10 inches high and is for two purposes, one to assist in the drainage, and the other to protect reckless drivers who may come around a turn too fast." As June of 1919 rolled around, the motoring public grew increasingly impatient. The Automobile Club of Southern California was inundated with inquiries as to when the road work would be completed. The Times pointed out that the approximately 250 cars and trucks traveling the route each day were driving an extra 23 miles, wasting valuable time, oil, and wear-and-tear on tires and parts. It was estimated the road closure was costing motorists an extra $500 a day in economic waste. Paving Complete Finally, on Nov. 16, 1919, the L.A. Times announced: "The famous Ridge Route, paved from end to end with solid concrete, is now open to traffic. Nothing has been spared to make this highway one of the finest mountain roads in the world. "The paving itself is 20 feet wide. On all turns, a curb of concrete protects motorists from possible danger. The Automobile Club of Southern California has posted the road in a most thorough way. Every sharp curve is marked and wherever a warning is needed an Auto Club sign gives it. The usual danger of collision on curves has been greatly decreased by cutting the banks on the inside of the turn. It is now possible for driver to get a clear view of the road ahead before they go into a turn." Grapevine Spoils the Party Motorists over the newly paved road were delighted as they traversed the Ridge Route, but as they approached the Grapevine, they were in for a most unpleasant surprise. As the Times described it: "The situation is like this. After leaving Lebec bound north, or the foot of the Tejon bound south, the motorist is most rudely jolted out of the twentieth-century era of good roads and slammed into the days of yore. Yea, he is 'plunked' one might say."

While the rest of the road had been paved, the Grapevine sector was just coming under construction, requiring slippery detours with grades up to 22 percent. "To begin at Lebec and work north, one rounds the corner and starts down the hill, over a high crowned road full of chucks and ruts. After slowing down to 10 miles per hour, he finds himself still banging around like a dry lima bean in an empty quart measure. After 7 miles of this, the real excitement begins as the 'Gas House' detour must be made. At the bridge just above the natural gas plant, one veers sharply to the left, through a fence and onto a road that would make any bad highway in the country blush with envy." Life was hard on the highway in those days. The Ridge Route traveler just could not win. Next time: More on the travails of driving the Ridge Route, the Lebec Hotel, and the demise of the road with the completion of the Ridge Route Alternate. Alan Pollack, M.D., is president of the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society.

|

SEE ALSO:

Ridge Route Series

Story by Harrison Scott 2004

Auto on Ridge Route ~Late 1910s

1918-1930

1920s

Castaic Area ~1920s

Serpentine Drive x2

Ridge Route ~1930s

Grapevine Grade (Mult.)

Speed Warning 1920s

Graceful Turns ~1930s

4-26-1937

Film: Gorman to Grapveine, Winter 1939

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.

The famous Ridge Route opened to great fanfare on Nov. 16, 1915. It was the first direct route over the mountains between Southern and Central California.

The famous Ridge Route opened to great fanfare on Nov. 16, 1915. It was the first direct route over the mountains between Southern and Central California.