|

|

|

Iconic Camulos Bell, Del Valle Portrait Come Home.

Two important pieces of local history that have been absent for nearly a century came home Saturday to Rancho Camulos Museum. Accompanied by several family members, Suzanne "Suzie" Daggett, lately of Nevada City, presented the museum with one of the three original "Home of Ramona" bells and a portrait of her great-grandmother in her wedding dress. Her great-grandmother was Josefa del Valle Forster (1861-1943), daughter of Ygnacio and Ysabel del Valle. The Del Valles once owned everything from Piru on the west to the edge of Soledad Canyon on the east. As a child, Josefa saw most of the 48,000-acre Rancho San Francisco (Santa Clarita Valley) slip from family ownership. By the time she became the titular head of the family ranch as an adult, only the Rancho Camulos section remained, 10 miles west of today's Valencia on scenic Highway 126. Although it appears to be unsigned, the portrait is attributed to Alexander Harmer (1856-1925), a famous California artist who settled in Santa Barbara. He was a frequent visitor to Camulos and even got married there himself. The gift was arranged by museum director Susan Falck, who invited another Del Valle descendant — museum volunteer Hillary Weireter — to be present for the handover. Weireter hadn't met her distant cousins face-to-face before Saturday. It's a big family. The portrait shows Josefa as she would have looked on Sept. 30, 1885, when she wed John Forster, scion of a San Juan Capistrano family that owned Rancho Santa Margarita in (now) Orange County. The Spanish-born Bishop Francisco Mora y Borrell of Los Angeles married them at Rancho Camulos. A petite woman, Josefa would wait 14 more years before bearing their first child. "She lived here at Camulos, and my great-grandfather lived in Los Angeles," Suzie Daggett said. "We don't know quite why, but this arrangement worked. They met up quite frequently." First son Yngacio Forster came along in February 1899. Josefa was pregnant with their second son, Juan, when her husband died Aug. 12, 1901. Josefa "wore black from the day her husband passed until she passed," Daggett said. As a Del Valle in the 1800s, Josefa was L.A. royalty — and devoutly Catholic. "She entertained constantly when she had money," Daggett said. "Big, long tables, full of bishops and cardinals and those who counted in Los Angeles. Lots of silver and china and everything. And that went away." Josefa's fortune reversed after her husband died. "She went from being extraordinary to ordinary," Daggett said. "The whole family did." Josefa ultimately lived in the same household as her granddaughter, Lorenita Forster Weisenberg — Daggett's mother. Which is how Daggett ended up with the portrait. "It hung in our house from the day I remember ... until my mom passed, and then it hung in our (Nevada City) house for a year, until Camulos was ready to receive her," Daggett said, referring to the recent restoration of the 1920 "small adobe" and the opening in June of the research library (by appointment only). "She is now back in her home where she belongs, in my estimation, because she is museum quality," Daggett said. "She is a beautiful, beautiful woman, and a kind woman who did a lot for California. (There is) a lot of history written about her, but it's kind of buried history."

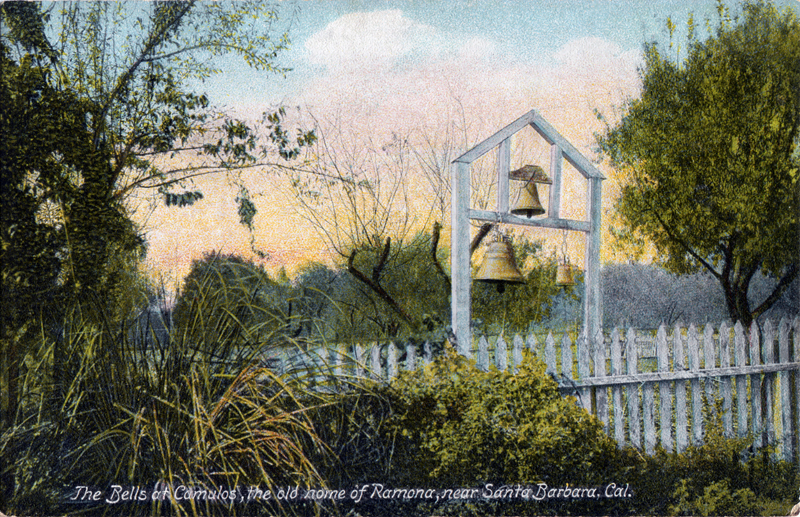

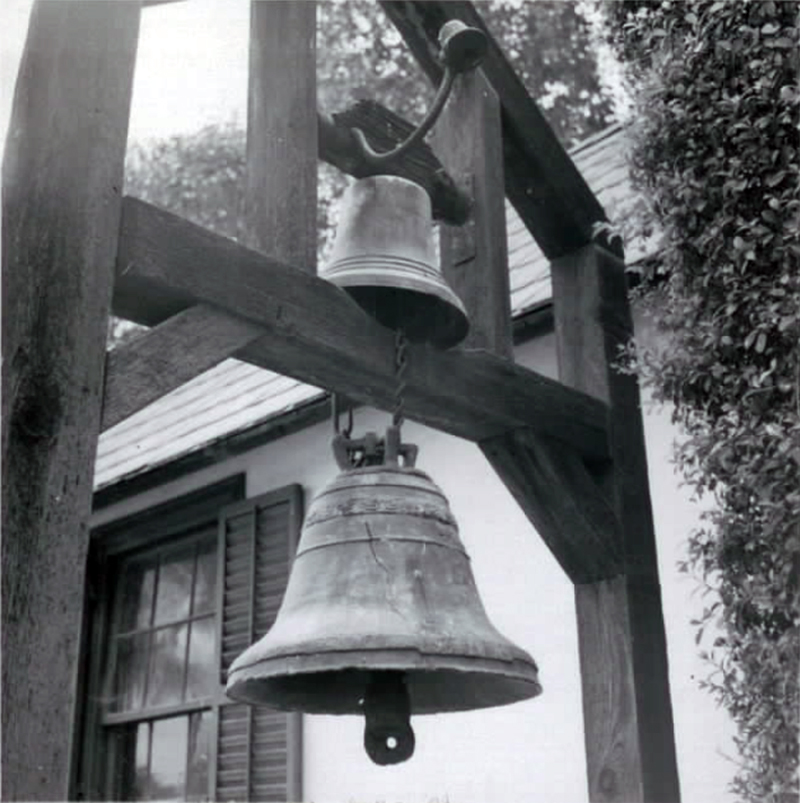

One thing buried, for the time being, is the meaning of a handwritten date on the back of the portrait frame — October 10, 1887. The frame itself has a patent date of 1883. Josefa's portrait is destined to hang alongside another Alexander Harmer portrait of Josefa's brother, Reginaldo del Valle, which was previously donated by another descendant. Reginaldo was president of the California State Senate in the 1880s and later served on the commission responsible for William Mulholland's L.A. water project. Josefa spoke Spanish; Reginaldo was bilingual. One major event of Josefa's young adulthood was the 1882 visit of Helen Hunt Jackson. The author modeled her epic 1884 novel, "Ramona," in part on the Del Valle family and Rancho Camulos. (Harmer also painted Jackson's portrait.) Jackson was an early Indian rights activist who hoped her romantic novel would reach audiences in ways her political prose did not. "Ramona" did reach audiences, but not in the way Jackson intended. The blockbuster best-seller of its day, "Ramona" sparked a massive westward migration to California as people flocked to see the idyllic places Jackson described — right down to the set of three mission bells at a fictionalized rancho. One of those bells disappeared around the time the Del Valle family sold Rancho Camulos in 1924. Now we know where it went. And now it's back to join the other two. "Somehow Josefa gave her son John (Juan) this bell," Daggett said. "When (he) died and his wife Madeline died, the bell was going to linger nowhere. Mom asked (my husband) Brent and I to go to San Francisco, to Mill Valley, and to abdicate the bell. Free the bell. So, the bell was freed from the deck of my grandfather's house and brought to my mom and dad's house at the beach in Oxnard, where it lived happily until they moved up to our neighborhood, Nevada City, where it lived happily until my mom passed and my dad passed. Now it has been delivered back to its rightful home here at Camulos." Genealogical research by Tricia Lemon Putnam.

|

• C. Rasmussen Story

Ygnacio Family Tree

Ygnacio 1808-1880

Family History: Del Castillo 1980

Del Valle Branding Iron, RSF 1830s-40s x5

Livestock Ledger 1853

History of Ownership

Wolfskill Foreclosure 1864

Labor Records

1919-1924

Ygnacio's L.A. Property 1871

Envelope: Reginaldo to Ysabel 1877–1883

James Walker Art

(1818-1889)

Ygnacio Bio 1889

Ysabel 1837-1905

Description 1879

Bedroom ~1890

Reginaldo Nominated Lt.Gov. 1890

Pico Oil Connection

Probate Filing, Death of Juventino, 1919

Reginaldo 1854/1938

Reginaldo Bio 1889

Lucretia 1892/1972 (Multiple Entries)

Nor. Cal. Basket mid-1800s

Bell, Portrait Come Home 10/28/2017

Reginaldo Recognized at UCLA 5/24/2019

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.