|

|

Construction of the Overland Mail Co. Stage Line in California.

© Gerald T. Ahnert

SCVHistory.com | January 2014.

|

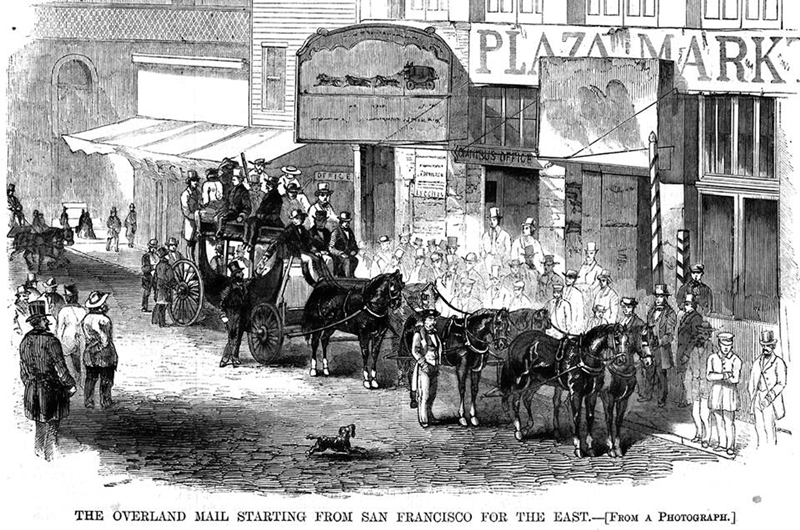

John Butterfield's Successful Bid for the Overland Mail Co. Contract Contract No. 12578 for $600,000 per annum for six years for a semi-weekly service was signed Sept. 16, 1857, by John Butterfield, his partners, and Postmaster General Aaron V. Brown. Butterfield met the terms for building the trail and started service from San Francisco one year later, on Sept. 14, 1858, exactly 10 minutes past midnight.[1]

John Butterfield was the president of this company, officially designated the Overland Mail Co. The Postmaster General stated his reason for choosing John Butterfield's bid[2]: ...–a route which no contractor had bid for, but one which, in the judgment of A.V. Brown, of Memphis, "had more advantages than disadvantages than any other." And, as John Butterfield & Co. had, in the opinion of Brown, "greater ability, qualification and experience than anybody else to carry out a mail service," John Butterfield & Co. was selected and preferred… San Antonio to San Diego Mail Line Before the Overland Mail Co. (OMC) started its service on the Southern Trail, there was another pioneering stage line of note. The San Antonio to San Diego Mail Line (SA&SD) was the first attempt to connect the East to the West with a mail-carrying stage line. Most of the travel was accomplished by stage, but part was on mule back — thus the nickname, "Jackass Mail." The trail for the line didn't exactly connect the East to the West, as it started in central-south Texas. Mail was brought to San Antonio from the South, and in Southern California, mail was delivered only to San Diego. This left out key cities such as San Francisco. It also ran only twice a month. The line used the old Emigrant Trail and established few stations. As an example, only one crude brush station was built in Arizona, at Maricopa Wells. The only two other places in Arizona used as possible stations were at Tucson and what was known as Peterman's, about 40 miles east of the Colorado River.[3] Although Butterfield's Overland Mail Co. did travel on some of the tracks made by the SA&SD line, the OMC made significant improvements by building new sections to shorten the trail.[4] In Arizona alone, the OMC built 23 new stations. The SA&SD started its service July 24, 1857, and ran until December 1858. As the OMC started its service in mid-September 1858, the services overlapped by about three months.

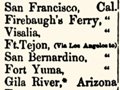

Correspondent Farwell noted in late October 1858[5], while at Butterfield's San Simon Stage Station in Arizona: "Opening from this is San Simon's Valley. Here is a new station, just established, where we changed horses, and here we met the San Diego mail." The SA&SD benefited for three months by this new section constructed by Butterfield. The OMC's route was better positioned to receive mail from the northeastern and southeastern United States for shipment to San Francisco, as the route had two starting points. One was at St. Louis, and the other at Memphis, Tenn. These trails met at Fort Smith, Ark. The OMC route served more states, territories, cities and towns than did the SA&SD, since the OMC’s route was 2,860 miles. The SA&SD’s route was 1,475 miles. Because the OMC route started at St. Louis, it truly connected the East to the West; in 1858, St. Louis was considered the jumping-off point for the Western frontier. Historians often debate who gets the honors for the first stage line to connect East and West. From many primary-source references, it appears the Overland Mail Co. was the first successful company to accomplish this important task. Overland Mail Co. and Its Involvement with Wells, Fargo and American Express Seven of the 11 owners of the OMC who signed the contract were also on the board of directors of two famous express companies. John Butterfield was one of the founding members of the American Express Co. in 1850.[6] Three of the OMC contract signers were on the board of directors of both Wells, Fargo & Co. and American Express Co. William G. Fargo was a director of the OMC; Henry Wells was not. To understand the intertwined relationship of these companies and their influence on each other, an understanding of the word "express" in this context is needed. The World Book Encyclopedia Dictionary gives the following definition: "A quick or direct means of sending things. Packages and money can be sent by express in trains or airplanes" or stagecoaches. Both Wells, Fargo & Co. and the American Express Co. furnished financial support to the OMC. Their investment increased over time. Wells, Fargo & Co. was the dominant financer,[7] as its wealth increased rapidly. In the beginning, its influence on the OMC and on other transportation lines amounted to the stage lines carrying its parcels. Ken Wheeling, a leading expert on wagons, carriages and stagecoaches, stated the following[8]: Although Wells, Fargo & Company shared board members with several stagecoach companies, it was not primarily in the stagecoach business. It was, first and foremost, an express company, concerned with expedition the shipment of almost anything between a paying sender and an intended addressee. At times, it found it necessary to subsidize this or that stage company in order that its own shipping business might not suffer from want of a carrier. An article in the Daily Alta California on Oct. 16, 1858, thanked Wells, Fargo & Co. for shipping Atlantic newspapers by express via the Overland Mail Co. After the formation of Wells, Fargo & Co. in 1852, the firm became involved in banking and the transporting of valuable shipments, such as gold from the California mines to banks in San Francisco. It would often use its own wagons and guards. It was forbidden to ship any valuables on the Overland Mail Co. stages, as shown in John Butterfield's order No. 8 in the company's Special Instructions issued to all employees: "No money, jewelry, bank notes, or valuables of any nature, will be allowed to be carried under any circumstances whatever." For this reason, no Overland Mail Co. stage on the Southern Trail was ever held up by outlaws. Many of the pioneering stage companies on the central trail, as well as the Overland Mail Co. on the Southern Trail, suffered some financial hardships. Wells, Fargo & Co. increased its investments in these troubled companies. Even before the OMC was moved to the central trail after March 1861 because of the impending Civil War, John Butterfield was voted out of office (in April 1860) for spending what was perceived as too much money on the efficient running of the line. Wells, Fargo & Co. threatened to foreclose because its loans and investments were not showing a profit. (Although no longer president, Butterfield remained a member of the board.) William Dinsmore, as president, took over the reins of the company. By 1866, Wells, Fargo & Co. achieved the Grand Consolidation of all of the independent companies on the central route — including the OMC. Wells, Fargo & Co. did not operate on the Southern Trail as a stage line during the OMC's service from September 1858 to its abandonment there in March 1861. Wells, Fargo & Co. Operates for First Time in California as Stage Line In Ken Wheeling's well documented article, "The Abbot-Downing and Company's Famous '30'" for the Overland Journal, he writes that Wells, Fargo & Co. still had not achieved the total running of a stage line with its logo on the side of a stagecoach until 1867: In the spring of 1867, the stagecoaches of the old Pioneer Stage Company were re-decorated and re-lettered. For the first time, stagecoaches in California bore the name of Wells, Fargo & Company on their transom rails. On April 20, 1867, Wells, Fargo & Co. placed its first order with Abbot-Downing & Co. for 30 Concord stagecoaches. They did not arrive at Salt Lake City to be put into use on the central line until June 20, 1868. For the first time, the name "Wells, Fargo & Company" appeared on the transom rails of new stagecoaches acquired by the firm. The Grand Consolidation of the stage lines on the central route by Wells, Fargo & Co. would be short-lived with the completion of the transcontinental railroad on May 10, 1869. Only two stagecoaches and the gear of a third survive from the original 30 ordered by Wells, Fargo & Co. The state of California owns the renovated No. 251, which is on loan to the Wells Fargo History Museum in Old Town San Diego.[9] Marquis L. Kenyon, Butterfield's Chief Architect of the Overland Mail Co. Line in California There are many primary-source references to support Marquis L. Kenyon's[10] involvement in building the infrastructure of the line. He was also one of the 11 owners of the OMC. He was not on the board of directors of Wells, Fargo & Co. or American Express and was directly under the supervision of John Butterfield. Many employees of the OMC had upstate New York connections. John Butterfield's home was in Utica, N.Y., but the head offices for the company were in New York City. Along with Butterfield, Kenyon had many years of experience in the staging business. Before his employment with the OMC, he was the proprietor of an extensive line of stages at Rome, N.Y., where he had resided since 1839.[11] Kenyon left New York by steamer and traveled to San Francisco in November 1857. With him were John Butterfield Jr.[12], F. De Ruyter and S.K. Nellis.[13] De Ruyter was on the construction crew that built Dragoon Springs Stage Station in Arizona. They had just left to go to a site on the bank of the San Pedro River to build a station when three Butterfield employees were massacred at the Dragoon Springs Stage Station on Sept. 8, 1858.[14] In the winter of 1857-1858, Kenyon's task was laying out the line. He traveled about 35 to 45 miles per day by mule, finding efficient routes through the designated corridor for the trail and selecting station sites.[15] John Butterfield Jr. was with Kenyon on this initial trip to supervise the layout of the trail. It was John Butterfield Jr. who was the driver of the first stage when the line opened for service between Tipton, Mo., and San Francisco. In June, Kenyon was engaged in setting up the line in California and hiring crews to construct stations and stock the road from San Francisco to San Bernardino. Mr. E.G. Stevens and a Mr. Hall were hired by Butterfield to stock the road and build stations on the selected sites from San Bernardino to Fort Yuma. To access San Bernardino, they had a difficult job clearing a trail over San Bernardino Hill and San Francisco Pass.[16] In late June, Kenyon announced that the stations were completed enough and stocked from San Francisco to Fort Yuma, and stages could be running twice a month on this section starting in August. He also stated that the line would be ready to meet the contract's requirement for service twice a week on the entire length of the trail on Sept. 15, 1858. In late August 1858, it was announced that 52 stations were ready for service in California.[17] Three stations were established in Mexico from about where New River crossed the Southern California border into Mexico, to the border of Arizona at the western bank of the Colorado River. This was done to avoid the sand dunes of southeastern California. It is not known if these three were counted in the total of 52 stations.

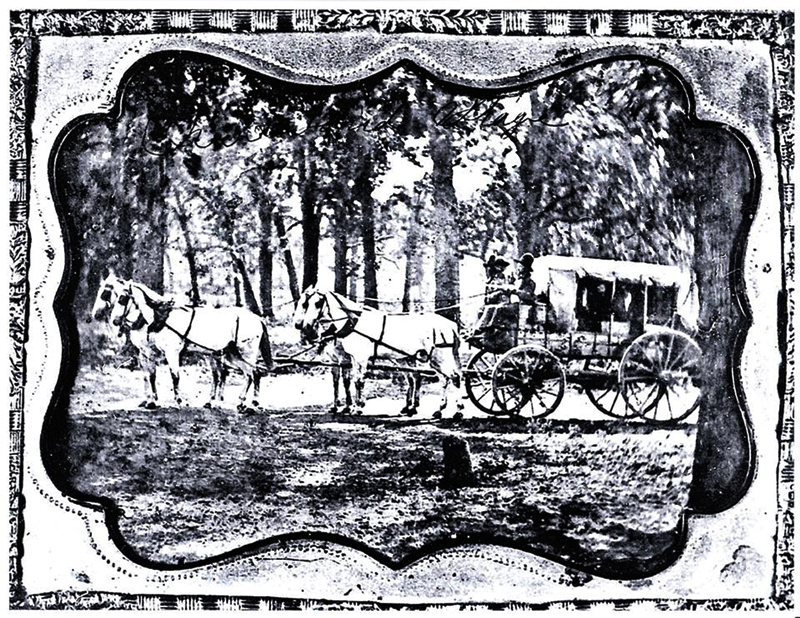

Many settlements and ranches between San Francisco and Los Angeles were contracted by the OMC to provide stage stations. For this reason, many of these stations were not named by Kenyon, but instead retained their existing names. One of the most notable was Warner's Ranch, which was established many years before Butterfield's service. Kenyon named some of the remote stations on the trail to Tipton. As an example, he gave five of the 26 stage stations in Arizona names from around his home in Rome. And one he named after himself — Kenyon's Stage Station in western Arizona. The next station to the west of Kenyon's he named Stanwix. Kenyon owned Stanwix Hall hotel in Rome. Three other names of stations in Arizona bore familiar names from near his home: Oneida, Mohawk and Seneca. A minimal number of stations was established to put the line into service by Sept. 15, 1858, but after service started, many more were added, and some sections of the trail were straightened. This was particularly evident in eastern Arizona.[18] Although the trail ran through an established corridor, the route of the trail as it existed on Sept. 15, 1858 had many local changes by March 1861 when the OMC ceased service on the Southern Trail. Kenyon stocked a line of the classic Concord stagecoaches from San Francisco to Los Angeles, but stage (celerity) wagons were used from Los Angeles to Fort Smith. One hundred of these stage wagons were designed to meet John Butterfield's specifications. They were built either in Albany or Troy, N.Y. Many were stocked at the stations, as the stages were changed about every 60 miles.[19] Kenyon resigned as a superintendent and director of the OMC in 1860 when the morale and discipline started to decline with the ousting of John Butterfield as president. He returned to his home in Rome, where he again participated in many transportation businesses. He died March 27, 1862, and is buried in the Rome Cemetery. John Butterfield, his son John J., and his main architect for the building of the trail, Marquis L. Kenyon, are recognized for their monumental achievement of establishing what was known as the world's longest stage line. There is a bill in Congress to give it its proper recognition and make the Butterfield Trail a National Historic Trail.

Notes. 1. G. Bailey, The Senate of the United States, Second Session, Thirty-fifth Congress, 1858-1859, Report of the Postmaster General, Appendix: "Great Overland Mail," Washington, October 18, 1858, published in Washington (D.C.) by William A. Harris Printer, 1859. This report contains Bailey's inspection of the line and tables of times arrived at significant points along the trail (pg. 739). 2. Sacramento Daily Union, November 2, 1858, "Immigrant Roads and Mail Routes Across the Continent." 3. The Senate of the United States, Second Session, Thirty-fifth Congress, 1858-1859, Report of the Postmaster General, "San Antonio and San Diego Mail Route," Washington, October 18, 1858, published in Washington, D.C., by William A. Harris Printer, 1859. The report of Superintendent for the San Antonio and San Diego Route, detailing his trip during November 1857 (pg. 744). 4. Gerald T. Ahnert, "The Construction of the Butterfield Trail in Eastern Arizona," in Desert Tracks, publication of the Southern Trails Chapter of the Oregon-California Trails Association, June 2013, pg. 18. 5. Daily Alta California, November 16, 1858, by J.M. Farwell. 6. Syracuse Daily Standard, April 5, 1850. 7. Letter from the Secretary of State, 46th Congress, 3d Session, Ex. Doc. No. 24, "Route 12578, California–St. Louis, Mo., to San Francisco, Cal. Overland Mail Company contractor in account with the United States." This record shows Wells, Fargo & Co.'s financial involvement (other than personal loans) starting June 29, 1860. 8. Kenneth Wheeling is Associate Editor of The Carriage Journal and director of the Carriage Association of America. Quote is from his article, "The Abbot, Downing & Company's Famous '30,'" in the Overland Journal, Vol. 23, No. 4 (2005-2006), pg. 142. The Overland Journal is a publication of the Oregon-California Trails Association. 9. Wheeling, ibid. 10. Marquis L. Kenyon is the correct spelling for his name. Newspapers misspelled his name in various ways, the most popular being "M.L. Kinyon." The 1860 Federal Census incorrectly spelled his name as "Marcus L. Kinyon." The Congressional Record copies of the contract also misspell his name as "M.L. Kinyon." 11. "Biographical Sketches of the State Officers and Members of the Legislature of the State of New York, in 1861," New York, 1861, pp. 213-214. 12. The Binghamton Press, March 23, 1909. 13. Evening Star, Washington, D.C., November 23, 1857. 14. Ahnert, Gerald T. "The Butterfield Trail and Overland Mail Company in Arizona, 1858-1861." Canastota, N.Y.: Canastota Publishing 2011:37. 15. Evening Star, Washington, D.C., April 29, 1858. 16. Los Angeles Star, June 12, 1858. 17. Los Angeles Star, June 26, 1858. 18. Gerald T. Ahnert, "The Construction of the Butterfield Trail in Eastern Arizona," in Desert Tracks, June 2013, pg. 18. 19. Gerald T. Ahnert, "Butterfield Overland Mail Company Stages on the Southern Trail," article to be published in the Overland Journal in 2014.

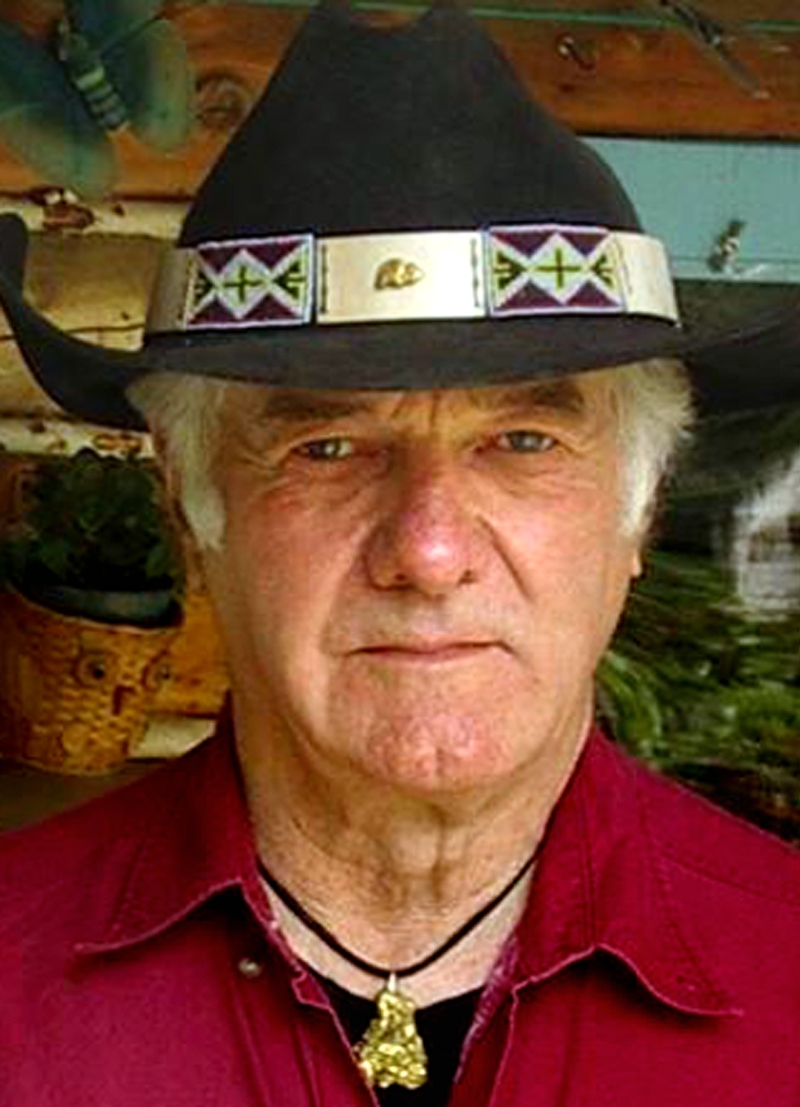

About the Author. Gerald T. Ahnert has been researching the history of the Butterfield Trail in Arizona since 1970, when an aerospace contract first took him to the Grand Canyon State. In 2011 his research culminated in the publication of his second book, "The Butterfield Trail and Overland Mail Co. in Arizona, 1858-1861." Ahnert is a member of the Arizona Historical Society, which honored him in 2011 for his efforts to preserve the trail on the Sentinel Plain in Western Arizona; and of the Southern Trails Chapter of the Oregon-California Trails Association. He has recently written about the Butterfield Trail for the association's Desert Tracks publication and for the Overland Journal. His articles have been published in the Sunday New York Times, Antiques Journal, Coin World and other hobby periodicals, and online by the California Parks Department. Before his wanderlust took hold, Ahnert had been a micro-electronic designer for the NASA-2 spaceflight simulator on the Apollo 11 project. Then, bitten by the trail bug, Ahnert and his wife spent 1973 and 1974 crossing the Sahara Desert on one of the world's longest desert trails, the Tanezrouf. For the past 35 years the couple has owned gold mining claims in the Klondike in Canada's Yukon Territory, where they make their summer home. The rest of the year they live in Syracuse, N.Y. — where Gerald studied photojournalism — except for January and February when they return to Arizona to warm up, walk the trail and lecture about the Overland Mail Co.

|

Butterfield's Overland Mail Stations, SCV & Environs

Read: Overland Mail Co. Stage Line in California

Backgrounder: Express Companies & Staging in California

Ripley: San Fernando (Newhall) Pass Part 11

Jackass Mail, 1857/61

Timetable, Southern Route Through Tejon 1858

Butterfield Coach 1858

Butterfield Celerity Wagon 1858

Butterfield Wagon 1861

Mud Wagon x4

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.