|

|

Stagecoach or Celerity Wagon?

A primer for those who write about the history of Butterfield's Overland Mail Company

© Gerald T. Ahnert

| January 2014.

|

There is a "mountain" of erroneous history concerning this famous stage line. Much comes from not correctly stating the official name of the company. Using the proper term will also help future researchers when they use search engines for their research. Here are a few suggestions for writers on this site to help in presenting our true history. In this age of search engines on the internet, it is very important to be specific. Always use the official name "Overland Mail Company" and if used with Butterfield's name state "Butterfield's Overland Mail Company." If "Butterfield" is used instead of "Butterfield's" it may suggest that Butterfield was part of the official name used on the lines equipment. This will go a long way to alleviate confusing the Butterfield Overland Despatch with the Overland Mail Company. The Butterfield Overland Despatch was a stage line on the central route several years after the Overland Mail Company closed its operations on the southern route. The "Butterfield Overland Despatch" was a completely different and unrelated line. Two unrelated people had the coincidence of having the same last name. When stating the name that was emblazoned on the side of the Butterfield's stagecoaches and stage wagons, always use "Overland Mail Company." There were no exceptions to this practice. When referring to the coaches they used from Fort Smith, Arkansas, to Los Angeles, California, always use the term "stage wagon" — not "stagecoach." He used exclusively the stage (celerity) wagons on this section, which was 70 percent of the trail. They were a very different style of stage. There were a few minor exceptions to this use at the start of the line in late 1858. When stating a general term for the line, always use Butterfield stage line — not Butterfield Stage Line, as capitalizing the "s" and "l" may give the impression to the readers that was the official name of the line. To also aid future researchers, use "stage station" instead of "station." This will help in eliminating the many other unrelated references that will pop up concerning railroads and the military.

About the Writer.

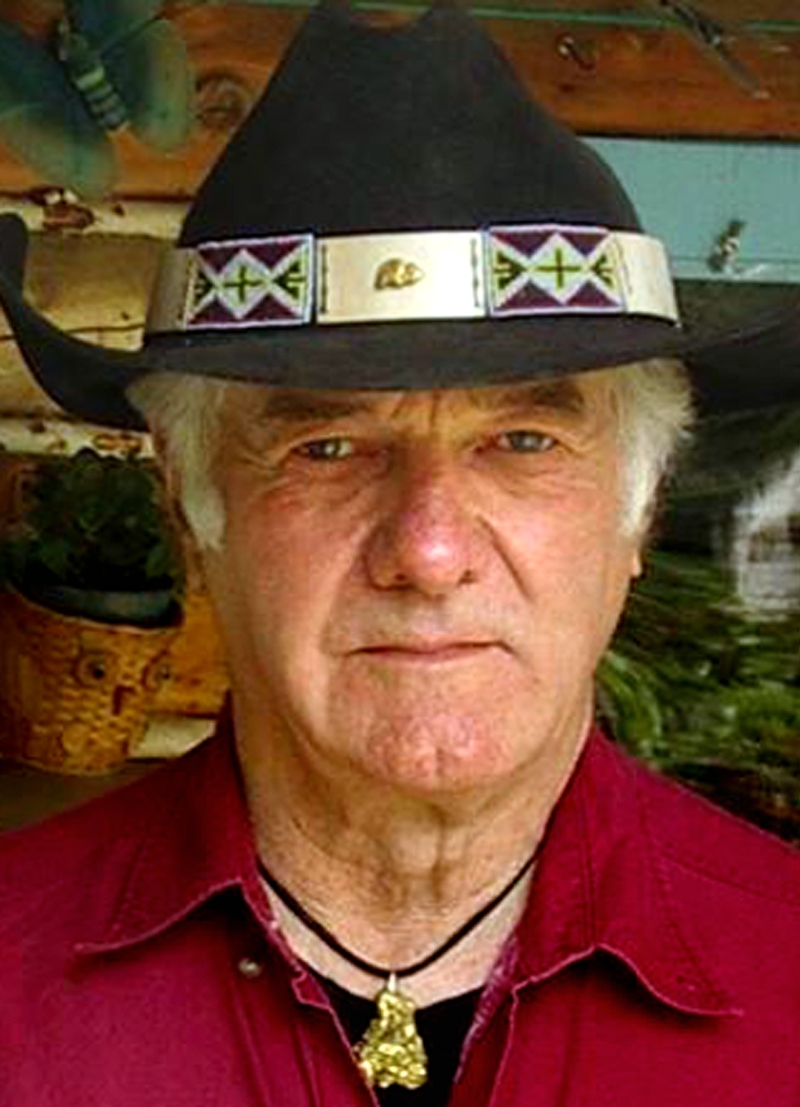

About the Author. Gerald T. Ahnert has been researching the history of the Butterfield Trail in Arizona since 1970, when an aerospace contract first took him to the Grand Canyon State. In 2011 his research culminated in the publication of his second book, "The Butterfield Trail and Overland Mail Co. in Arizona, 1858-1861." Ahnert is a member of the Arizona Historical Society, which honored him in 2011 for his efforts to preserve the trail on the Sentinel Plain in Western Arizona; and of the Southern Trails Chapter of the Oregon-California Trails Association. He has recently written about the Butterfield Trail for the association's Desert Tracks publication and for the Overland Journal. His articles have been published in the Sunday New York Times, Antiques Journal, Coin World and other hobby periodicals, and online by the California Parks Department. Before his wanderlust took hold, Ahnert had been a micro-electronic designer for the NASA-2 spaceflight simulator on the Apollo 11 project. Then, bitten by the trail bug, Ahnert and his wife spent 1973 and 1974 crossing the Sahara Desert on one of the world's longest desert trails, the Tanezrouf. For the past 35 years the couple has owned gold mining claims in the Klondike in Canada's Yukon Territory, where they make their summer home. The rest of the year they live in Syracuse, N.Y. — where Gerald studied photojournalism — except for January and February when they return to Arizona to warm up, walk the trail and lecture about the Overland Mail Co.

|

Butterfield's Overland Mail Stations, SCV & Environs

Read: Overland Mail Co. Stage Line in California

Backgrounder: Express Companies & Staging in California

Ripley: San Fernando (Newhall) Pass Part 11

Jackass Mail, 1857/61

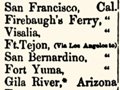

Timetable, Southern Route Through Tejon 1858

Butterfield Coach 1858

Butterfield Celerity Wagon 1858

Butterfield Wagon 1861

Mud Wagon x4

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.