|

|

|

The First Highways Commerce is predicated on transportation — which at that early date meant roads. The first Legislature (1850) determined: "All roads shall be considered public highways, which are now used as such and have been declared such by Order of the Court of Sessions or Board of Supervisors within their respective counties." On May 19, 1851, the Los Angeles Court of Sessions detailed the road from the Pueblo of Los Angeles to San Bernardino, and the East, existing roads between Missions and also "The Tulare Road to the Mines by the Tulares" from Cahuenga or Verdugo (Glendale) to ex-Mission San Fernando, thence to Rancho San Francisco, thence to the Cañada des Alamos (San Francisquito Canyon), thence to Rabbit Lake (Elizabeth Lake) — and that is how the roads became legalized on Rancho San Francisco. The Records of the Board of Supervisors of this County, back in those formative days, show more appropriations and expenditures to get to and through Rancho San Francisco than all the rest of the County for its first decade. An authoritative study detailing the opening of road over the San Fernando, or Newhall, Pass appeared in Vols. 29-30 of the Quarterly of the Historical Society of Southern California, authored by Vernette Snyder Ripley. The First Stagecoach Major Horace Bell's account ("Reminiscences of a Ranger") of the first stage ride over the pass is, in any event, contemporary and certainly self-explanatory. He writes:

Believe it or not, the foregoing is not an exaggeration. A few years ago the writer [Perkins}, with Pierre Daries and Thomas Mitchell, both of old local families and then with the Forestry [Dept.], went over the Grapevine Canyon Road in a jeep. Much work has been done since 1850, but the old tracks, straight up precipitous faces of solid rock, are so obviously impossible to travel, except on foot, that one cannot believe the Butterfield Stages and the Overland Stages used that route — but they did. Phineas Banning's Ride Horace Bell continues:

Honestly, didn 't Major Bell have a wonderful control of words? Much later, another pioneer, John Kuhrts, wrote:

The Butterfield Mail

The full quotation from the Ormsby articles through the Pass to Hart's[14] (Lyon's Station) and on to Ft. Tejon follows:

Traces Remain The old ruts still visible detail this old route. At the junction of Highway 6 [Sierra Highway — ed.] and San Fernando Road, turn left up the Elsmere Canyon and travel west less than a mile, to an old road going southerly up a canyon. You may have to climb a Forestry gate, a Standard Oil locked gate in one-quarter mile with Forestry lock. If you haven't arranged access — keep on this road; it is a Forestry road over the crest and down into Grapevine Canyon, on the San Fernando side of the range. Portions of this road have been built for Forestry access, but the observer will see the old ruts of the Stage road ground into the exposed sandstone of almost precipitious cliffs over which — believe it or not — the pioneers drove their stages and wagons.

If you have walked through the old Grapevine Road, you might return via Beale's Cut, where you will see the old bar and pick marks as clearly outlined on the exposed walls of the Cut as they were when freshly made. The writer was once fortunate enough to go through the Grapevine Road in a Forestry jeep with Pierre Daries and Thomas Mitchell, both of whose families have been here for three-fourths of a century. As has been mentioned, the jeep road does not stick literally to the original route all of the way for the reason the jeep couldn't get sufficient footing where the stage went. Grapevine Canyon Where is Grapevine Canyon? In the Mexican era but one trail ran from Rancho San Francisco to the Mission at San Fernando. Because of its rocks, grades and general handicaps, it was called "El Camino Desesperar" by some — the Road of Despair — so christened by an unfortunate dowager whose carreta had upended in the defile. Going towards the Mission from the Rancho one turned easterly up Whitney Canyon at the junction of Highway 6 and San Fernando Road (a half-mile up is now a locked Standard Oil Co. gate) and about a mile up, turned southerly up a canyon headed to the crest of the range, and bearing wheel tracks visible. After crossing the summit and starting down the San Fernando Valley slope, still in or on the canyon road, one used to enter quite a patch of wild grapevines — a few of which are still to be found — from which obviously the canyon derived its name. From the mouth of the canyon, the trail ran practically in a straight line to the Mission, diverted only by what used to be a very deep arroyo but now filled to road level. The Main Highways As of 1850, access to our Valley from the south, the San Fernando Valley, was through the Grapevine Canyon. Westwards there was a sandy rut running all of the way to Mission San Buenaventura. To the north there was the very rocky trail through San Francisquito Canyon. All roads were equally bad, the Ventura road substituting sand and water crossings for the rocks and precipitous steeps of the other trails. After all, pedestrians do not require paved roads. The only wheeled vehicles were the springless wooden disc-wheeled carretas, pulled by oxen. The north-south road was the important consideration, for there was an unbelievable influx of population in the middle section of California during the gold rush; that meant mining camps and markets. The merchants of the pueblos already trading through a 1,500-mile radius were not overlooking the short hauls opening up. At that time the population of Los Angeles County was 3,550 — 486 houses of which 278 were in the pueblo. Prior to the gold rush, cattle — and that was about all produced in this county — were valued at from $1 to $2 per head. There was a ready market on the Mother Lode at $15 per head — of course, you walked the 500 miles, a bagatelle to a vaquero. History shows commerce to be more profitable than mining. Six White Horses That first Butterfield Stage was drawn by six white horses. Stage schedule was tri-weekly. The California Stage Company had been running since 1855. It ultimately entered the Stage consolidations of James Birch, known as the Telegraph line. Ventura had a local stage line connecting with the major routes at either Moore's or Hart's stations. Stage lines, of course, run primarily on stock and wheels, but they couldn't get far without stations at very short intervals. That, of course, explains Lyon Station, our first settlement at [the south] end of the Valley — excluding, of course, the aboriginal population. It was located at the junction of Highway 6 and San Fernando Road of today, and is now marked only by the old graveyard on the Needham ranch. Its name changed with that of the current stage-tender, or station operator. It was known variously as "Fountain's," "Hart's," "Hosmers," "Andrews," "Lyon's," at various dates. San Fernando Mission, or Lopez stage station was also known as "Twenty-five-mile," from whence it was 8.79 miles to Lyon Station. There was a "Moore's Station" located at the mouth of San Francisquito Canyon that probably ended when the main road switched to Soledad Canyon. In 1860 that station, then called "Hollandsville," was the scene of a small slaughter when three Mexicans attacked the station, killing J. T. Williams from Milwaukee, Wis., and G.W. Laughly of Hebron, Ohio. The Moore family is still with us living at their home on Spruce Street. Lyon Station Cyrus and Sanford Lyon were still operating the station at Lyon in 1856. Harris Newmark recalls stopping there and seeing one of the brothers start filling a molasses jug, get into a discussion, and return his attention to the jug only after the molasses had flooded the dirt floor. The Lyon brothers were very well known in Los Angeles County in the early days. Sanford Lyon, father of the late Addi Lyon, lies in the graveyard at Lyon Station, since 1885[15]. Shortly thereafter the family left here for the southern end of the county, and they always retained their local ranch upon which Mrs. Addi Lyon lives[16]. To date, no picture of Lyon Station, as it was, has been located, but a contemporary description of 1875 leaves little to the imagination.

This makes up the sum total of Lyon Station. Lyon Station was important from about 1855 to 1875. It was the mail and supply point of the Valley for a quarter-century. In an early County Directory of about 1875, 20 men were registered from Lyon Station, as against eight from Plaberitas and 30 from Soledad. Of the names there listed, descendants of the Mitchell brothers, the Powell brothers, Francis Moore, the Lopez Brothers, F. Pina, Sanford Lyon, L. Contraris and John Howe live here today. The first post office of the Valley was commissioned at Lyon Station in 1874. It was discontinued in 1879. The old graveyard at Lyon Station should have mention. Many of our oldest pioneers, such as Sanford Lyon, sleep there. For some reason, the graves all seem to be on the southern side of the little canyon, and appear from the canyon floor almost to the summit of the hill. Some few are marked with granite, or, as in the case of the Whitney's (the pioneer ranchers or farmers of Whitney Canyon), with marble. Turnpikes United States occupation of California had started in 1847, but not until 1850 did the first Legislature meet. Foremost was the problem of tying together the widely scattered mining camps of the Mother Lode section and outlying areas being prospected by the '49ers, and doing it without money. For this reason, the Legislature made it easy for anyone road-minded to build roads. By the Plank & Turnpike Road Act (Section 894, General Laws 1850) it was made possible for any nine or more people to organize a joint stock company for construction of plank or turnpike roads by making and subscribing to a declaration of intention or organization or description of proposed road, terminal and route, which declaration, after one week's publication, allowed them to elect officers, designate corporate name and file certificate of same, and proceed to the survey, estimate of costs and issuance of stock. Apparently the only deadline tied to the new road company was a 30-day time limit on preliminary organization and a six-month time limit of the final organization for stock subscription, these restrictions evidentiy being solely for the purpose of hurrying road construction. This Association could condemn private property for right of way, but (Section 909) could not go within 50 feet of a dwellng house, nor interfere with mining flumes, or mine operation. In 1878 there were 68 of these turnpike companies still operating. In 1857, it was found necessary to limit the toll charges imposed by an act allowing supervisors in whose district the roads were built, to set the tolls from year to year. Companies failing to conform to this could be prosecuted before the Justice Court of the Township. The Wagon Road Act The above regulations governed only plank and turnpike roads. Wagon roads were even more simply handled. Under wagon road companies, as approved April 22, 1853, pg. 928, the same general rules were followed except that the life of the wagon road companies was held at 10 years, subject to the authority from supervisors or courts of session of counties through which proposed roads run; no office need be maintained, the books could be left with the county clerk. And under Section 931, it provided that the entire cost of the road plus 20 percent per annum interest, should be repaid to the company, after which the toll should be reduced to merely yield operating income. Compare the setup with that under which the bridge companies operate at San Francisco; it is surprising how little alteration was necessary for today's problems. It was a criminal misdemeanor to delay passengers or conveyances unreasonably by a toll gate keeper; to overcharge the public; to break or deface milestones; or obstruct open road. Refusal to pay the just toll drew a $25 fine plus damages, while swinging around the toll gate cost an extra $5. E.F. Beale Edward Fitzgerald Beale was a pioneer of great initiative and ability. He had come to California with General Kearny, served both in the Army and Navy, had been Superintendent of Indian Affairs in California and Nevada in 1852 and held many federal posts of importance. In the middle [18]50s, with his partner Samuel A. Bishop, he acquired title to a tremendous Kern County acreage (La Liebre Ranch). At one time he was the federally appointed Surveyor General of California and Nevada under President Lincoln. There is a story that Lincoln was once asked if he would reappoint Beale to that office, to which Lincoln replied, "No, he apparently becomes monarch of all he surveys." Driving back and forth from the Pueblo to his ranch, Beale was only too well aware of the transportation difficulties at the Newhall Pass: Time lost waiting while wagons were windlassed up the slope; scattered loads salvaged from the canyon and hillside — and flour was then universally shipped in wooden barrels; the bother of setting drags for brakes on any wheeled vehicle. First Road Efforts In 1860, Dr. John S. Griffin, J.G. Winston, Gabriel Allen, and J.C. Welsh were empowered to put in a toll road from San Fernando Mission to the arroyo of the Santa Clara River. That seems to have been as far as any action went. In 1861, a similar Act empowering Charles R. Brinly, Andres Pico and James R. Vineyard was passed. This frianchise very shortly was in the possession of E.F. Beale. Quoting from the Los Angeles Star, April 4,1863:

Cut Dug by Hand That cut, slicing the range cleanly, has been standing ever since construction with practically no sloughing[17]. Dug before the days of giant powder, the marks of the steel picks stand out clearly on the perpendicular walls today. Most of the tolls were paid in gold dust. The gold scales upon which it was weighed very recently were still in the hands of the late Mrs. MacAlonan, whose first husband, Tom Dunn, took over the Robbins interest in 1873. The Toll House was a five-room, whitewashed adobe. Two bedrooms flanked a living room on the east front, shaded by a porch. A counter-weighted pole, for barrier (said to have been brought down from the defunct Soledad Toll Gate) was fastened to a porch pillar. Tolls Resisted The very idea of paying toll was repugnant to the sensitive natures of the early Basque sheep men. Many were the days some of them spent working their flocks over the mountains some little distance from the Cut. The right of way covered one mile each side of the Pass. Many a herder was sadly aggrieved after spending a week getting his flock over the hills, to meet the toll gate keeper and a constable, where Saugus now stands[18], demanding and collecting tolls for the flocks had encroached on the right of way coming across. In 1875, Mrs. Dunn, temporarily keeping the gate during her husband's absence, was assured by a group of horsemen that a party yet to arrive would pay the tolls — but they didn't. Mrs. Dunn hastily collected her rifle and horse and went after her husband on the south slope. With a constable, the horsemen were pursued and overtaken at San Francisquito, where they were relieved of $16.50; $2.75 was the original toll, the rest balm for the toll gate keepers' injured feelings and the constable. The late H. Clay Needham's favorite story of the old cut was of the early pioneer whose wife and daughter were driving up the trail in a wagon. Halfway up they encountered a herd of cattle on the way down. The cattle milled and swarmed; the wagon was upset, its tongue broken, and the ladies spilled out, though otherwise undamaged. A few minutes later the husband and father arrived on the scene and surveyed the wreckage. With a set jaw he extracted his rifle from the wagon and went in pursuit of the herders. He returned a couple of hours later. "Well," he said, "Guess they won't pull that stunt again." "Did you kill them?" awesomely asked a bystander. "Nope, but I made 'em pay me a dollar for that wagon tongue." And he had. Beale's Cut What has Beale's Cut to do with Rancho San Francisco? Just about everything. Through that Cut poured an ever increasing flow of traffic. The Pueblo [of Los Angeles] commerce was diverted through the Rancho, for the Cut saved a week freighting over the Cajon Pass road. It blanketed the hopes of Ventura harbor which might have successfully competed with Cajon Pass. Wherever traffic flows, there is a slop-over, if you will, and along the edges of the road will be small farms, rest houses, mining activities, all of which came to pass and the eastern end of Rancho San Francisco sort of became divorced in all but the name from the bulk of the Grant [the Rancho], all due to Beale's developed idea — the Cut. It was in the [18]80s, about '86, that the franchise expired and the Cut became part of the County road system until 1910, when it was superseded by the Newhall Tunnel. Autos Killed Cut Motor traffic was the death of the old Cut. Motor cars simply weren't good enough to get over that steep, rocky road. Old settlers living in the Cut's vicinity did very well for years hauling stalled automobiles one way and another, thus successfully increasing meager incomes. The widening of Highway 99 and elimination of the [Newhall auto] Tunnel in 1938 left the toll house site buried under 40 feet of fill. It had been marked by an almond tree planted by Mrs. Dunn when she first came to the Toll House as a bride of 16. The flowering of the almond was an annual reminder of Beale's great Cut and toll gate. The Del Valles Shortly after the United States of America took over California from the Mexican Government, there was an Act of Congress covering land titles, under which the original land claimants had a certain length of time to file title claims under United States laws to their properties, which, after legal delays, expensive hearings, and Bureau procrastinations, would lead to issuance of Patent title. Hence in 1852, the Del Valle interests, consisting of Jacoba Feliz, widow of Antonio del Valle, later married to Jose Salazar; Ygnacio, Maria, Magdalena, Jose Antonio, Jose Ygnacio and Conception del Valle, the children, petitioned for title of Rancho San Francisco, "commencing at the junction of a creek, called the Arroyo of Piro, or Piraic with the said driver, thence ascending the said river including the valley on both sides thereof to and including the hills or portions thereof, upon both sides of the river, up to and including a place called 'la Soledad' situated in the then County of Los Angeles and State aforesaid." Legal Costs Ruinous The patent finally came through in 1875 — yes, 23 years later, and it was the legal costs of such proceedings that started most of the old grants to bankruptcy. The proceedings were complicated by the necessity of probate of Antonio del Valle's estate, completed in 1859 — incidentally, this was Case No. 2 of the probate courts of the County of Los Angeles — with appointment of Jose Salazar [Jacoba's husband] as administrator. The first survey seems to have been done by Henry Hancock in 1852, at which time the boundaries seem to have been whittled down to the 11-square-league limit allowable under the Mexican Land Laws of 1824, around 48,000 acres from the original 102,000 acres. As was customary, Hancock surveyed the 48,000 acres in the areas desired by his clients. Some Land Left Over This shrinkage left quite a strip of territory between the ranch ex-Mission San Fernando and Rancho San Francisco consisting almost entirely of hills and mountains too rugged for use, and of no known value as of that date. The boundary had been fixed for a decade when Ygnacio del Valle, who seems to have succeeded his father Antonio as the active head of the family, finally concluded the deal with the Philadelphia and California Petroleum Company of Thomas Scott. The Great S.P. Tunnel Near the western boundary of the ranch, things were very decidedly happening. The sleepy little valley, hitherto only a thoroughfare for miners and prospectors en route to and from the mines of the Slate Range, the Soledad Canyon; had picked up rather heavy wagon traffic from the mines since completion of Beale's Cut. In 1875, Henry M. Newhall had acquired title apparently through the agency of Thomas R. Bard. (As a matter of fact, the Suey Ranch at Santa Maria came into his hands at about the same date.) Mr. Newhall had done very well with his auction firm in San Francisco, the San Francisco and San Jose Railroad, and his other interests, and was starting to accumulate the huge acreages that were to be the foundation of the great family fortune. As a director of the Southern Pacific Railroad, he was well posted on developments and the last to have been surprised when Railroad Canyon, to the south of Newhall, became the scene of frenzied activity. The San Francisco Tunnel was under way a matter of only weeks after his latest acquisition. Across the mountains, there was a thread of white canvas and dust streaks, for at least three different places along the 7,000-foot route of the Railroad Tunnel, camps had been established on top of the hills, each the mouth of a 12x12-foot, 30-degree incline shaft running down to tunnel level. At the portals of both the north and south side of the mountain were to be found construction camps. Details of the Job The tunnel itself was trapezoidal, surmounted by an arch. The floor was 14 feet wide; the sides rose 16 feet to the arch, which was centered 21 feet above the floor. It was worked by an advance heading made in the arch, setting stulls, or 10x14 timber sets as the ground was cut out, then the tunnel body was cut. Normally the timber sets were three feet apart, although at points of abnormal strain, they were as close as nine inches. The roofs were chiseled into place with steel and double jacks, the arches held in place by 3-inch planking bolted to the stulls. The hill itself was a mass of blue clay, sand, gravel, and saturated with water or oil, with the result that slippage of earth bodies became a constant threat and the handling of water a terrific problem employing as many as nine steam pumps. In spite of their drainage facilities, a shaft, idle for pump repair and 325 feet in depth, filled to within five feet of the surface while idle. Boiler explosions were not uncommon and took a heavy toll from the working force. At maximum, more than 1,500 men were employed at the tunnel — 1,000 Chinamen, as laborers in the eight working faces, which ran both ways from the shafts; 350 white mechanics — probably timber men, 60 wood choppers, 30 or 40 cooks, eight blacksmiths, teamsters, etc. The white men worked 12 hours for $2.60 per day and bound, meaning board and lodging. The Chinese received $1 a day. It Was Thirsty Work A big commissary carrying a full line of supplies for both whites and Chinese was operated by Sissen and Co. and 15 different saloons are reported. How they were distributed was not mentioned. Between sliding ground, greasy shales and exploding boilers, this construction job was literally a man-killer, but, starting in July 1875, it was completed in 1876, having left about $100,000 monthly in the area in payroll, and the same amount in local purchases of supplies. In its day, this tunnel was a major construction project, costing more than $3 million and presenting new problems in technique daily. It wouldn't be easy today. The tremendous flows of water encountered ultimately drained the mountain to the tunnel level. Thirty years back, there was quite a stream flowing from the north portal of the tunnel that today is dry. The fern banks once to be found in the little canyons have all dried up, the ferns themselves only a memory. That always happens in Southern California with inadequate annual rainfalls. The converse is also true; in the case of a water well with a bottom pressure of, say, 250 pounds, which roughly means a rise in water level of 500 feet, higher strata of less pressures, unless sealed off from the well, have the tendency to flood the weaker-pressured strata to the damage of both well production records and water zone. The completion of the railroad tunnel naturally led shortly to the driving of the golden spike at Lang, Sept. 5, 1876[19]. Regular railroad schedule sort of automatically eliminated the old Lyon Stage station. Last Stage Station Would you know what to do if you had a stage station antedated by a railroad? George R. Dilly, last operator of the stage station, knew.

Incidentally, there were still stages running from Andrews Station to Santa Barbara, for in April of 1877, one is told that the stages have dispensed with the "old Wells Fargo & Co. Express boxes and have instead iron safes with two locks, screwed down underneath the front seat of the stage inside. The locks are manufactured in such a way that powder will not explode them nor affect them in any way." One wonders if that was a healthier arrangement for the passengers. The Start of Newhall The railroad's completion had led to the establishment of new stations and new towns. From Henry M. Newhall, the railroad acquired a townsite, down by the present site of Saugus[20], to be called Newhall, but the sandy wastes were unpopular, and what there was of the town, such as Campton's store, picked up and moved to the new location 2 1/2 miles south. There, there were trees and less blowing sands. You might think that a new town would have been welcomed in Los Angeles County, and in July of 1876 its existence was acknowledged in the following slightly unfriendly terms:

And at this point, while the pueblo/metropolis welcomes the new member of its county family with such open-hearted friendliness, the reader leaves Rancho San Francisco, henceforth to be known as the Newhall Ranch. So we will follow the fortunes of the puling infant town of Newhall for awhile...

ERRATA Butterfield Trial historian Gerald Ahnert writes (2019):

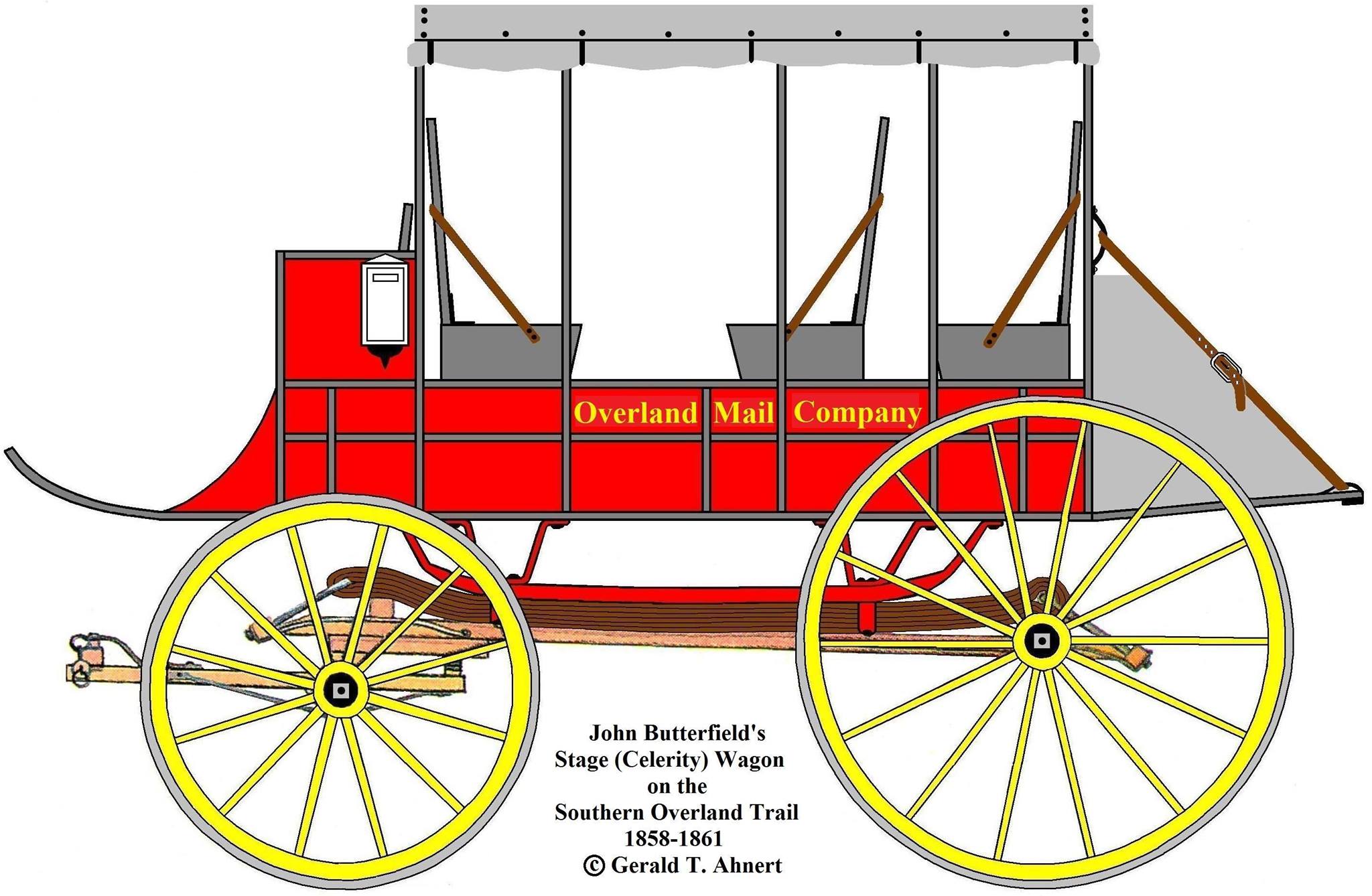

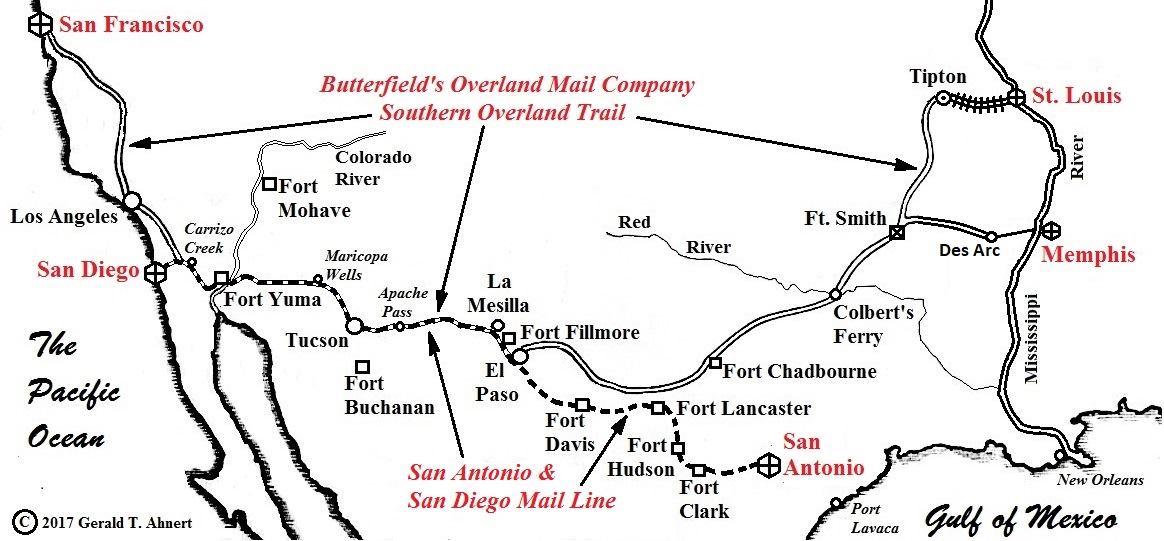

A few notes of clarification. The official name of John Butterfield's stage line was "Overland Mail Company." Replicas of his stages often incorrectly use the name of "Butterfield" on the transom rail, but "Overland Mail Company" was the only name used. The Pony Express was not in competition with Butterfield's Overland Mail Company. Initially it was an independent mail service operating without a government contract on the Central Overland Trail. The Pony Express actually joined with the Overland Mail Company contract on July 1, 1861. In March 1861, Butterfield was ordered to transfer all equipment and employees to the Union held Central Overland Trail to complete the six-year contract because of the start of the Civil War. It was ordered to start on the Central Overland Trail on July 1, 1861, and was when the Pony express came under the Overland Mail Company Contract.

Post Master representative Goddard Baily was on the first Butterfield stage out of San Francisco to inspect the line. In his official report he stated there were 139 stations but within a year more were added for a total of 175. Although matched horses were used for the first mail on a short section, mainly wild mules and mustangs were used. The San Antonio and San Diego Mail Line (The Jackass Mail) was not mentioned in this article. They built very few stations. Only one was built in Arizona at Maricopa Wells. The line use only seven stages of various types, often very worn out wagons that would break down often. The mail was rarely carried beyond Tucson by wagon but had to be transported by mule (although their ads stated only 100 miles were by mule) to make the contract deadline. This line ran on 900 miles of the Butterfield Trail at the same time as Butterfield's Overland Mail Company. Butterfield's stages did not stop for the passengers to sleep, but the San Antonio and San Diego Mail Line stages did stop for the passengers to sleep. In an 1860 newspaper article, San Antonio and San Diego Mail Line Superintendent Isiah Woods congratulated Butterfield for making the trail more efficient for his line and emigrants.

|

Butterfield's Overland Mail Stations, SCV & Environs

Read: Overland Mail Co. Stage Line in California

Backgrounder: Express Companies & Staging in California

Ripley: San Fernando (Newhall) Pass Part 11

Jackass Mail, 1857/61

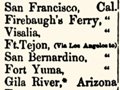

Timetable, Southern Route Through Tejon 1858

Butterfield Coach 1858

Butterfield Celerity Wagon 1858

Butterfield Wagon 1861

Mud Wagon x4

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.