|

|

The San Fernando (Newhall) Pass.

Part 11. 1860: The Longest Stage Ride in the World.

The Quarterly, Historical Society of Southern California, March 1948.

|

1860, June 14. An English author, William Tallack,1 left San Francisco on the Butterfield Overland Mail, returning to Europe from Australia. "The writer — often felt doubtful as to how far he might be able to endure a continuous ride of five hundred and forty hours, with no other intermission than a stoppage of about forty minutes twice a day, and a walk, from time to time, over the more difficult ground, or up and down stiff hills and mountain passes, and with only such repose at night as could be obtained whilst in a sitting posture and closely wedged in by fellow-travellers and tightly filled mailbags. ... Fourth Day. Southern California. "Near midnight our conductor called out, 'Straighten yourselves up!' in preparation for some very rough ground that we were just approaching which had been broken by fissures and banks, caused by an earthquake.2 In about an hour after these arousing jolts we drew up at the foot of the Tejon Pass.3

"The Tejon station was a store kept by a dry sort of Yankee, who, after moving about very leisurely, and scarcely deigning to answer any questions put him, set before us a supper of goat's flesh and coffee. After making a hearty meal we had again to shift into another vehicle similar to the preceeding." ("A mud wagon — a light van with black curtains.")4 "It being one o'clock in the morning, and a dark night, we had to be very careful that none of our respective packages or blankets were left behind in the hurried operation of changing; so we tumbled hastily into our new wagon, wrapping ourselves up in coats or blankets nearly as they came to hand, waiting till morning for more light and leisure to see which was our own. "By means of a blanket each, in addition to an overcoat, we managed to settle down warmly and closely together for a jolting but sound slumber. What with mail-bags and passengers we were so tightly squeezed that there was scarcely room for any jerking about separately in our places, but we were kept steady and compact, only shaking 'in one piece' with the vehicle itself. "Thus closely sleeping, we ascended fifteen miles of a mountain road, except for a part of the ascent, where we had to walk — not so pleasant a stretch as sometimes, on account of the darkness, sleepiness, and the occasional crossing of streams in our path.5 ... "We had now re-entered the Coast Range, and were winding down the romantic twenty-two mile San Francisquito Pass, a lovely region of tree and blossom, cliff and stream. Half way through it we had a wash and a good breakfast at a ranch, where we were warned that a hunter had that morning shot a bear a little lower down the valley, that the animal had only been wounded, and had retired amongst the trees and rocks close to our route, whence he might possibly make his appearance on our passing by. To the disappointment of the passengers, nothing was seen of him. "In the afternoon we entered the San Fernando Pass, a short but a very stiff one. Here our vehicle stuck fast in a narrow gorge. The horses could not move it, though aided by ourselves. Happily there was a waggon [sic] just behind us, whose team we borrowed, and, by dint of pulling and pushing all together, we soon got up the ascent. "This was the only time during the journey that we came to a deadlock, and it was also the only time that we were travelling in company with another vehicle going in the same direction. "On emerging from the San Fernando Pass we came to a new aspect of country and vegetation, and to a population retaining more of the Spanish and Mexican element than Northern California, as indicated by conversation and wayside notices in the Spanish language, and by the style of dress and prevalence of adobe houses. "The sunny plains and vineyards of Ciudad de los Angeles (the City of Angels) were now spread before us, whilst in the foreground rose, in the light of sunset, the purple sierras of San Gorgonio. The plains were covered with a profusion of varied and tangled vegetation, especially yellow and crimson cacti and prickly pear, oleanders, mesembryanthemums, sunflowers, mustard, and large elder trees, cotton-wood and the black chestnut, whilst the undulations were thickly covered with masses of small flowers, glowing in the evening like a purple velvet carpeting." ... 1860. By 1860 the Butterfield Overland Mail was doing a prosperous business. They had one hundred stage coaches for the road; they were hiring seven or eight hundred drivers among their other employees and had a rolling stock of fifteen hundred horses and mules.6 To top it all they were carrying more mail than the ocean steamers were handling.7 Their time east was cut from twenty-one to eighteen or nineteen days from Los Angeles. Later in the year they were no longer using the drab, hard-seated "mud wagons" between Los Angeles and San Francisco, in which Tallack had made his trip that June fourteenth. The travellers rocked along over the high San Fernando Pass, when they were not obliged to get out and walk, in brightly painted, heavy Concord coaches, whose better upholstery made them more comfortable on the rough, sharp-twisting road.8 1861, February. The intense, bitter feeling of the approaching Civil War had spread across the country. In late February, 1861 the Butterfield stage route, running through Texas, had been badly cut up by war-fare with bands of guerrillas.9 "Almost immediately, after the commencement of the Civil War in the states, this Southern Overland Express was discontinued,"10 the contract was terminated in March, 1861.11 1861, March. Early that same month a new contract was made with the government. The Central Overland Company and the Pikes Peak Express Company agreed to handle the mail and passengers over their stage line from St. Joseph, Missouri to Salt Lake City, Utah. Then John Butterfield and the old Overland Mail Company would carry them on from there, west to San Francisco, and northwest to Placerville.12 California, with the other states in the Union, felt the uncertainties and bitterness of the Civil War. There were sharp, conflicting opinions in the south of the state and in the small town of Los Angeles particularly. It was found necessary to move troops in for military protection. 1861, May 3.

"Headquarters of the Department of the Pacific

San Francisco May 3, 1861.

Bvt. Major J. H. Carleton

Captain, First Dragoons, Fort Tejon Cal:

Sir: The commanding general directs you to establish a camp at the most eligible position in the immediate vicinity of Los Angeles, capable of fulfilling the conditions called for in the enclosed letter of instructions to Captain Hancock, assistant quartermaster. The two companies from Fort Mojave will be included in your encampment and in your command. I am, sir, very respectively your obedient servant, W.W. Mackall, Assistant Adjutant-General"13 1861, May 7. Captain Winfield Scott Hancock to whom Brigadier E.V. Sumner had previously issued orders to "select an eligible encampment for the troops as near Los Angeles as possible," replied: "I have the honor to report that the site for an encampment for the troops has been selected, which will be assigned to them unless it is not approved by the general commanding. It is outside of town, beyond all buildings some distance, and directly in front of my corral, and in full view of it.... But the advantage is that you do not have to pass through town to get to the point to be protected, which would be the case were they encamped along the river above the town."14 1861, June 7. San Francisco.

"Commanding Officer

Fort Tejon Cal.

Fort Tejon will be abandoned and the garrison and property transferred to Los Angeles. Be prepared to move as soon as the order is received by mail. By order: D.C. Buell, Assistant Adjutant General.15 1861, June 19. Co. B. 1st Dragoons under Captain Davidson, on Wednesday morning June 19, entered its new quarters at Camp Fitzgerald,16 Los Angeles, and joined the rest of the garrison previously sent from Ft. Tejon. At the Fort, in the Canada de las Uvas, were left Lieut. Starr, a corporal and one private to guard the public stores.17 When the Butterfield Overland Mail was withdrawn, the discontinuance of the exciting arrival of the rumbling stage coaches with their dusty eastern passengers and eastern mail, left a gap in the life of the pueblo. But the local stages still crossed the valley and rattled up the stiff San Fernando Pass and through the high cut for way points beyond. With the country on tension during the Civil War, and new unrest among the Indians, neither did the loss of Fort Tejon up in the Canada de las Uvas, lessen the movement of troops over the tough grade. NOTES. 1. The Overland Mail. Book One, p. 129. Walter Lang. Written by William Tallack. 2. The earthquake of Jan. 9th, 1857. 3. Fort Tejon Pass. 4. Overland Mail. Book One, p, 136. Walter Lang. 5. The Canada de las Uvas, now "The Grapevine." 6. A History of Travel in America. Semour Dunbar. Vol. 4, p. 1319. 7. Via Western Express & Stagecoach. Oscar O. Winther, p. 1l9. 8. Sixty Years in Southern California. Harris Newmark, p. 267. 9. Six Horses. Cap't. William Banning & George H. Banning, p. 1l9. 10. The Overland Mail. Book One. Walter Lang. Foot-note by William Tallack. p. 163. 11. The Overland Mail. Book One. p. 6. Introduction, Walter Lang. 12. Via Western Express & Stagecoach. Oscar Osburn Winther. p. 138. 13. Story of El Tejon, Part Two, p. 1l9. Arthur Woodward. 14. Story of El Tejon, Part Two. Arthur Woodward. p. 138. 15. Ibid. p. 123. 16. Westside of Broadway between 1st and 2nd St. Arthur Woodward. 17. Story of El Tejon. Part Two. p. 123. Arthur Woodward.

|

Butterfield's Overland Mail Stations, SCV & Environs

Read: Overland Mail Co. Stage Line in California

Backgrounder: Express Companies & Staging in California

Ripley: San Fernando (Newhall) Pass Part 11

Jackass Mail, 1857/61

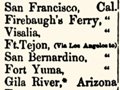

Timetable, Southern Route Through Tejon 1858

Butterfield Coach 1858

Butterfield Celerity Wagon 1858

Butterfield Wagon 1861

Mud Wagon x4

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.