Thank you, Shannon (Kelley, Head of Public Programs for the UCLA Film & Television Archive).

I bring two greetings to you this evening. The first is from Michal Bregant, general director of Národní filmový archiv, Czech Republic. Dr. Bregant writes:

The National Film Archive in Prague is proud to have been helpful during this — and many other — international restoration projects. The primary mission of the NFA is to preserve our national film heritage and to make it accessible for new generations of audiences, but as we know, cinema has always been an international adventure — so the NFA remains open to all kinds of international cooperation, as with "Ramona," both now, and in the future.

For my part, I would like to specifically thank Dr. Bregant and his staff, including Vladimír Opěla, Věroslav Hába, and Karel Zima, all of whom were instrumental in the task of bringing "Ramona" back to America.

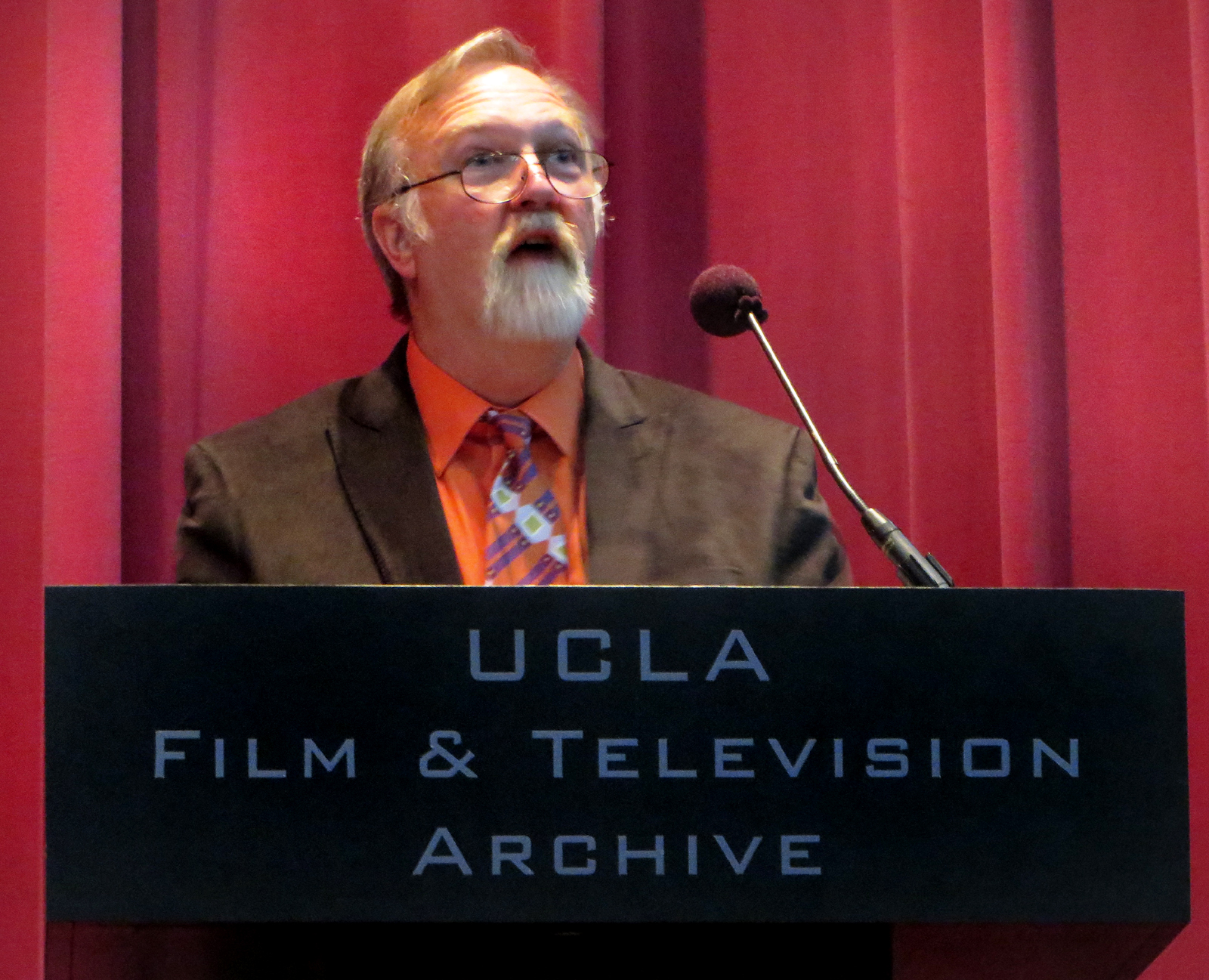

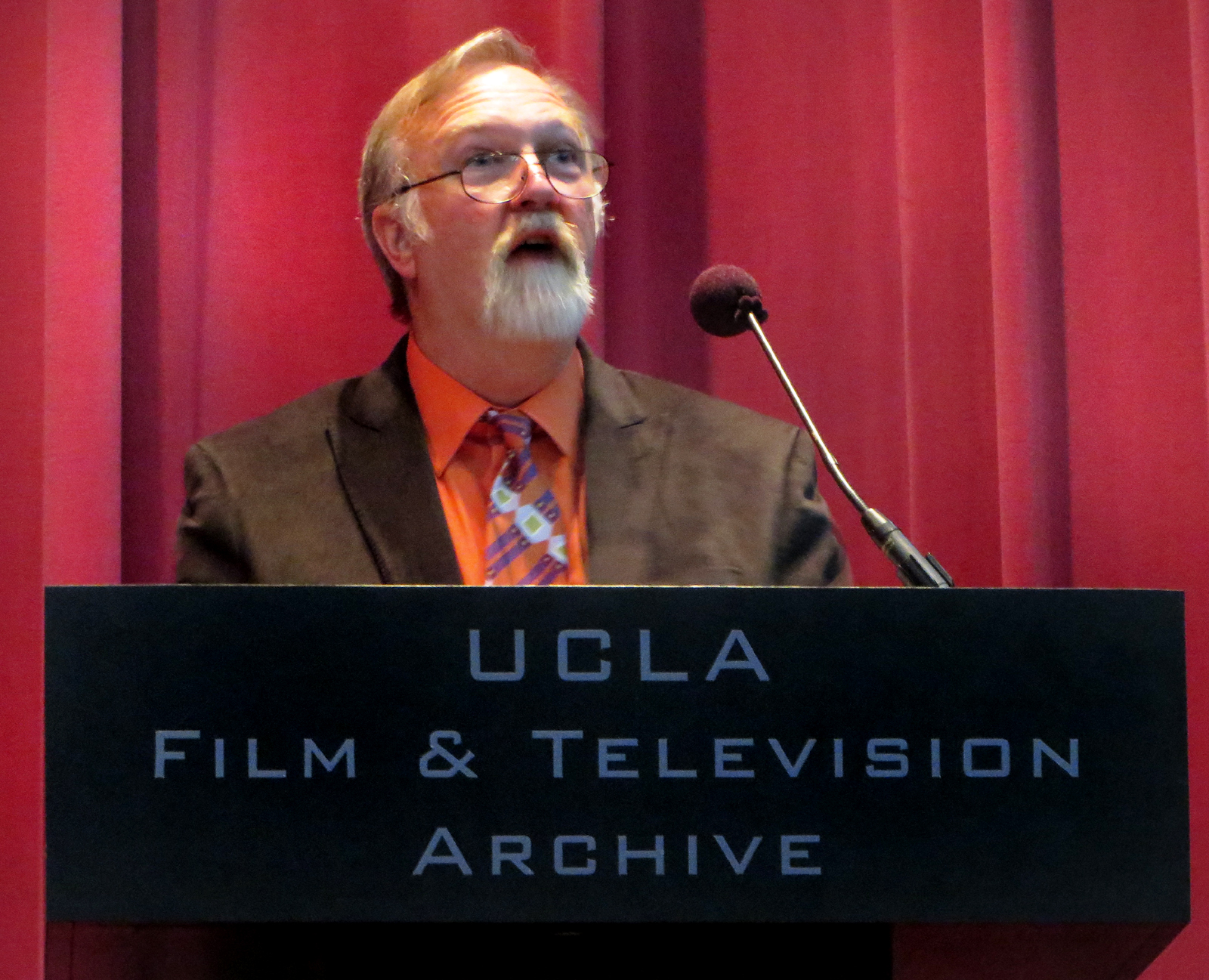

Hugh Munro Neely addresses a sellout crowd at the Hammer Museum's Billy Wilder Theater, March 29, 2014. Photos: SCVTV.

|

I spoke with Shep Houghton on the phone last week, and I bring his greetings to you, as well. When Shep was 13 years old, his parents moved the family to Hollywood, just a block from several movie studios. Shep was kind of bored on weekends, because he couldn't find enough kids to organize a game of stick ball.

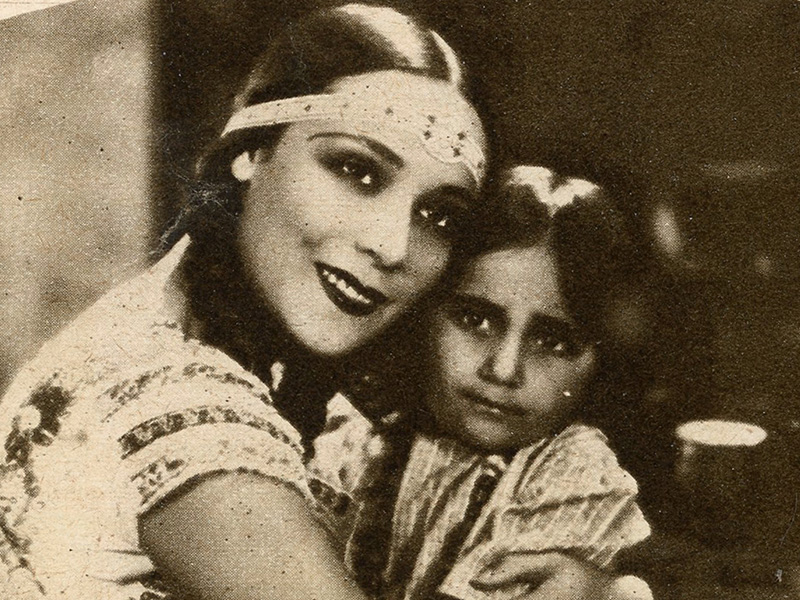

One Saturday, Shep was wandering down a street when when a man popped out of a studio gate, saying "Hey, kid, wanna be in a movie? We need another extra." Shep was ushered through the gate, into a building where he was costumed, and then out onto a bustling village set for "Ramona." An assistant director gave him the basics: Shep was to run with a dog, across the street on cue. Shep was not introduced to director Edwin Carewe, but he did recognize the striking Dolores Del Rio, who was also on set that day. Lights! Camera! Action! Shep worked several takes. When done he returned the costume, collected $5, and walked out the gate of Paradise.

From then on, every Saturday, Shep signed up for extra work. He became a regular. He found he could dance and very occasionally did bit parts. He appeared in two films directed by Joseph von Sternberg, a slew of Busby Berkeley musicals, DeMille's "Cleopatra," "A Midsummer Night's Dream," "Gone with the Wind," Objective Burma," "The Big Sleep," "Around the World in 80 Days," "Imitation of Life" and "Hello Dolly." He became President of the Screen Extras Guild. His last film credit is Robert Wise's 1975 production, "The Hindenburg." A full career.

It started with "Ramona." And what was the thing that magnetized Shep to the movies? What most impressed him in that fleeing half hour on his first day on a set? "More than anything else," he told me, "I got to see Dolores Del Rio, and she was beautiful, the most beautiful woman I had ever seen."

Shep sends his greetings to you tonight from his home in Hoodsport, Washington, where he lives with his wife Mabel. He is 99 years old and turns 100 in June.

Shep sends his greetings to you tonight from his home in Hoodsport, Washington, where he lives with his wife Mabel. He is 99 years old and turns 100 in June.

Now I want to tell you one more story before we start. In doing so, I'll be mention a number of names of people and of institutions, some Shannon has already mentioned, some are familiar, some not, most you'll forget before the night's out. They are important, though; the names must be pronounced. Many of these individuals have devoted their careers, or their entire lives, to saving and returning to us our moving image legacy for this and future generations.

It is a delicate legacy. The substructure is volatile. It must be actively preserved. So though you may not be able to recite these names when I am done, I hope you will take a moment, as the lights begin to dim, to give up silent thanks to the professional archivists who have made this evening possible.

You see ... 86 years and 1 day ago, Edwin Carewe's production of "Ramona" premiered in Los Angeles. Hundreds of prints of the film were distributed across the country. Still more in Central and South America, and in Europe. This deeply pacifist, meltingly romantic version of Helen Hunt Jackson's story was widely viewed and frequently praised, while a simple love song with the same name, vigorously marketed with the film, enjoyed a similar success.

This morning I counted 33 copies of this sheet music available for purchase on eBay. A piece of sheet music, printed on paper, can survive for centuries. But motion picture film is not so durable. In time, the film prints of "Ramona" were either junked from overuse, recycled for their silver content, or silently decomposed into chemical dust. "Ramona" was thought to be a lost film. Yet somehow, one print survived. It survived because of the work of four film archives. As best we can tell, here's what happened:

During World War II, a single Czechoslovakian print of "Ramona" was confiscated by the Nazis and sent to Berlin. At the war's end, Soviet soldiers looted the Reichsfilmarchiv and sent the film, along with many others, to the Soviet Union, where it was deposited in the Russian archive, Gosfilmofond, outside of Moscow.

Gosfilmofond is an archive of international scope, a huge repository. Today it holds some 70,000 titles from Russia and from around the world. It would be fair to say that "Ramona" became a needle in an archival haystack.

Now jump forward to the 1960s. A Czech archivist by the name of Myrtil Frida visits Gosfilmofond. Mr. Frida is something of a legend within the Czech archive community. My friend Věroslav Hába described Mr. Frida as "the genuine soul of the archive, and head historian during very difficult times of ideological darkness in our country."

Mr. Frida was also something else. He was the leading expert and exponent of American films in communist Czechoslovakia.

Mr. Frida was going through many cans of film in Russia when he discovered a print of an American film with Czech language titles. When he returned to the Czechoslovak National Film Archive, this dedicated man carried "Ramona" with him. Although it is unusual, there is no indication that Gosfilmofond kept a print or negative for themselves. Over the years, Mr. Frida and his staff at Národní filmový archiv saved many American films, even though this was not an ideological priority.

Neely leads a panel discussion following the premiere, March 29, 2014.

|

In 1987, the Czech archive was the only archive in the world to report to the International Federation of Film Archives that it held a copy of "Ramona" in its collection. However, after the fall of communism, reference to "Ramona" was unaccountably dropped in future reports. Often this happens when a film print is found to have decomposed before it could be saved. But fortunately, not this time.

In late 2009 and 2010, Joanna Hearne, and then Dydia DeLyser and I viewed the surviving print in Prague, and over the next four years, helped to coordinate its return to America, where Mike Mashon, Rob Stone, Lynanne Schweighofer and the team at the Library of Congress' film archive preserved and lovingly restored the film. Phil Brigandi, Dydia DeLyser and Klara Molacek carefully translated the Czech titles into English.

As best we can tell, you, tonight, will be the first audience in over 80 years to see this film. But thanks to the archives, and to the people I have already named, you will not be the last.

Tonight, as the Mont-Alto Motion Picture Orchestra prepares to perform the overture, we can also thank Diane Allen, granddaughter of Edwin Carewe, and the UCLA Film & Television Archive, including Jan Christopher Horak, Shannon Kelley, Paul Malcolm, Kelly Gramml, and their whole crew for this opportunity to experience the world premiere of the restoration of one of the the blockbuster romances of 1928, "Ramona."

Thank you.

Hugh Munro Neely is a film historian and former curator of the Mary Pickford Institute of Film Education. In 2010 he learned of the existence of a print

of Edwin Carewe's "Ramona" (1928) in the Czech film archive and hatched a successful plan to remove it from the list of lost films.