|

|

1857 Fort Tejon Earthquake: SoCal's Last Real "Big One"

By Aron J. Meltzner, California Institute of Technology[1]

Post Return[2] | January 1998

|

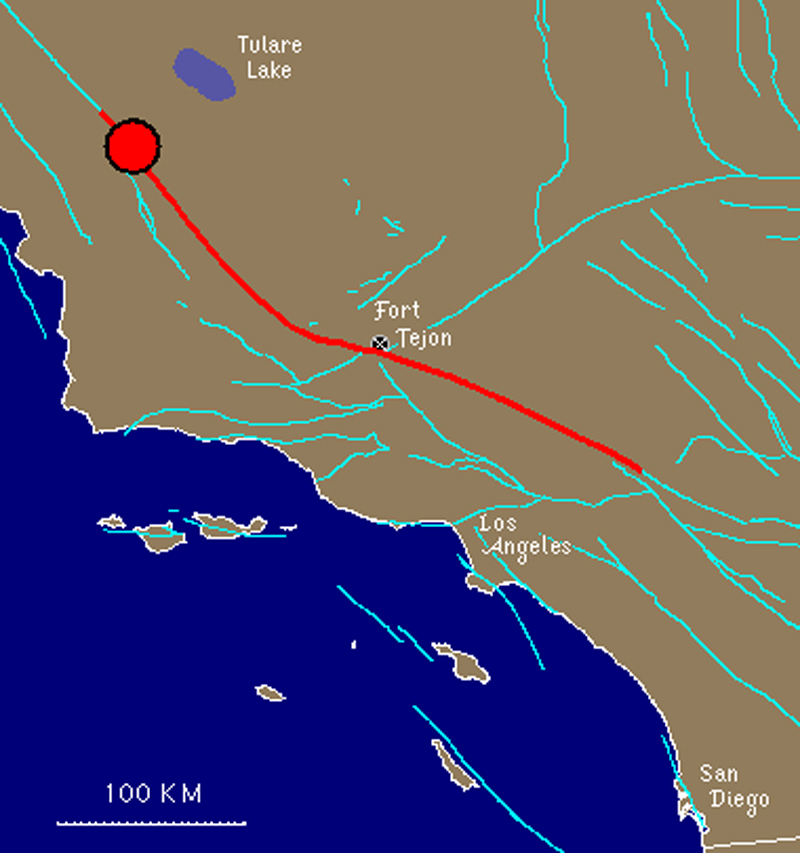

Only 34 years earlier, in 1872, Owens Valley in eastern California was rocked by an earthquake that was felt over good portions of both California and present-day Nevada. And the largest earthquake to hit Southern California in historic times occurred on January 9, 1857. It came to be known as the great "Fort Tejon" earthquake — although such appellation could be very misleading. Fort Tejon, in fact, was not the epicenter, nor was it even near the epicenter of the earthquake. Surface rupture originated northwest of Parkfield in Monterey County and propagated southeastward for over 360 km (225 miles) along the San Andreas Fault to the Cajon Pass northwest of San Bernardino.

Technically, Parkfield was the epicenter of this earthquake, as it was the origin of the rupture, but most scientists would be more concerned with the extent and location of the entire rupture; Fort Tejon was approximately the midway point of the rupture. The earthquake actually acquired its name because Fort Tejon was the only populated locality near the fault, and naturally, the Fort suffered more damage than the rest of sparsely-populated 1857 Southern California. In comparison to the other "great" earthquakes of historic times, the 1857 "Fort Tejon" earthquake was larger than the 1872 Owens Valley (estimated magnitude 7.8) quake, and was equally as large as, if not larger than, the 1906 "San Francisco" earthquake (estimated magnitude 7.9-8.0). Estimates for "Fort Tejon" are also in the vicinity of magnitude 8.0. The 1857 and 1906 events were both on the San Andreas Fault, although the 1906 earthquake ruptured the northern segment of the fault, from Hollister (San Benito Co.) northward, for 400 km (250 miles). Duration of shaking, along the fault, for both 1857 and 1906 is estimated to be as long as 2 minutes. In areas away from the fault, such as Los Angeles, San Bernardino and Santa Barbara, damage from 1857 was surprisingly light, although it is unclear how modern high-rises would respond to the long-period motion experienced at significant distances from large earthquakes. High-rises might be more susceptible to long-period ground motion than low buildings. Fort Tejon, on the other hand, suffered considerable damage from the mainshock, and it was battered by aftershocks for months and years to come — both a direct consequence of the Fort's proximity to the fault.

Two large aftershocks (approximate magnitudes 6.0-6.5) occurred within a week following the mainshock, which were felt over much of Southern California, although aftershocks were still being felt on a weekly basis at Fort Tejon over a year later. And it is expected that if any other locations along or near the fault (i.e., Wrightwood, Palmdale, Frazier Park or Taft) were populated back then, those locations would have reported similar intensities during the mainshock to those at Fort Tejon, and those locations could have experienced just as many aftershocks. The 1857 quake was the last so-called "Big One" in Southern California, and a similar event will almost certainly happen again in the future. Questions remain, however, as to when it will occur, and whether the next "Big One" will be as big as 1857. Los Angeles appears to have fared well last time, but it remains unclear how modern structures will respond in the future. It turns out that for Los Angeles, San Bernardino and Santa Barbara, blind thrust faults and other local faults are a bigger risk than the San Andreas Fault, simply because the former are closer to the population centers and because we know less about them. But for Fort Tejon, Palmdale and other cities along the San Andreas, the San Andreas remains the biggest threat. Only by continued monitoring and research can we hope to understand and reduce the seismic hazard over all of Southern California. We can never prevent earthquakes, but by knowing what may happen, we can prepare for them. Notes. 1. Meltzner wrote this article as an undergraduate student at CalTech in Pasadena, where he studied geological and planetary sciences. Today (2014) he is a senior research fellow at the Earth Observatory of Singapore, which conducts fundamental research on earthquakes, volcanoes, tsunamis and climate change in Southeast Asia. 2. Post Return is a monthly publication of Fort Tejon State Historic Park.

|

Video: Field Guide to the San Andreas Fault

1857 Fort Tejon Quake

Fault in Palmdale

Geology of Canyon Country (Dort 1948)

Strike-Slip Displacement (Crowell 1954)

Winterer & Durham 1962

Castaic Geology (Stitt 1981)

Soledad Basin (Muehlberger 1954)

Inventory of State Park Collection

Self-Guided Tour 1996

Huell Howser Program 1999

Hotel Plan 1858

Ruins (Mult.)

Rancho La Liebre 1929 (Story)

Postcard 1930s

Flying A Gasoline 1938

Home Movie 1939

Book: Old Adobes (Cullimore 1949)

Travelogue 1949

Old Gate Pre-1950

Officers' Quarters ~1950s

Headquarters Bldg. 1957 (Story)

Brochure Pre-1967

Enlisted Men's Barracks (Mult.)

• 1857 Earthquake (1)

Peter Lebeck Exhumed 1890

Lebeck Story 1901

Lebeck Grave 1957 (Story)

Lebeck Oak ~1960s

Lebeck Oak & Grave Marker x7

Lebeck Bark x2

Lebeck Sculpture x3

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.